![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Un-American Schooling: Anticommunist Discourse and Martin Luther King Jr.

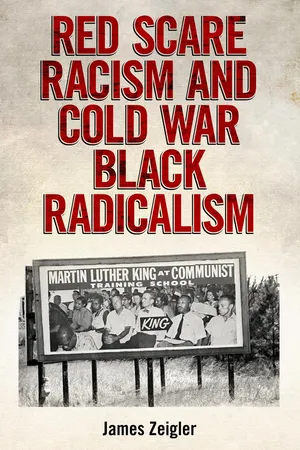

On the second day of the historic march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, 300 civil rights activists, including King, passed the billboard that pretends to capture him at a “Communist Training School.” It had been placed directly in their path only a few hours earlier. The oversized public accusation was an insult added to injuries. The demonstrators needed three tries over two weeks to succeed in crossing Pettus Bridge on the edge of Selma, nearly fifty-four miles from their destination. In one of the most notorious episodes in the history of the struggle for civil rights, on March 7, 1965, the “possemen” and deputies of Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark turned back the first attempt with the “Bloody Sunday” assault on the nonviolent protesters. Already sparked, in part, by the murder near Selma of unarmed activist Jimmie Lee Jackson, this first, failed march would see seventeen more people hospitalized.

Forty-eight hours later, King had arrived to lead a second effort. With many of the 2,500 demonstrators unaware of the plan, the group advanced to the bridge, knelt for prayer, and then returned to Selma to await a court’s judgment on a petition for authority to conduct the march. Miscommunication and strategic differences about the decision to stop short this second try exacerbated rifts between King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). And, on the night of this second effort, defenders of Jim Crow segregation beat another activist to the ground, this time the white minister James Reeb who died in a hospital from his injuries two days later. With legal approval, on March 21 a group finally proceeded across the bridge and away from Selma.1 Four days later, as many as 25,000 supporters joined the demonstration at the steps of the state capitol in Montgomery. Prior to these now legendary days of violence and public exposure, months of effort in Selma to register African Americans to vote had already been costly. Thousands of arrests and incidents of jailhouse torture had been endured by activists with only modest gains locally, but the harrowing optics of nonviolent protesters under assault by the police force and mobs of angry white citizens would prove a turning point across the United States for support of civil rights.2

In the context of the furious and punishing reaction against the black freedom struggle in Selma, the sudden appearance of this billboard on the morning of March 22 must have seemed to the demonstrators simultaneously predictable and surreal. Its all-too-familiar charge repeats the reactionary strategy of referring to the civil rights movement and the Communist Party as if they were one and the same in order to suggest that black American protest is actually un-American sedition and, conversely, that support for the traditions of the segregated South is an expression of American patriotism.3 Taking its smear campaign to the streets in time to impugn federal legislation that would become the Voting Rights Act, the John Birch Society sponsored more than two hundred of the displays across the South.4 The sign insinuates that the recent sacrifices and persistent risks suffered by the civil rights movement were unnecessary theatrics engineered by the CPUSA and its handlers in the Kremlin to stir up racial antagonisms that would undermine the stability of everyday life in the United States, opening the country to ruin or even a takeover by the USSR. Such suspicion must have seemed a fantastic alibi for the naked, visceral racism with which activists were confronted during the voter registration initiatives in Selma and surrounding areas.

Those on the march must also have regarded the sign’s threatening message as tired. The photograph had already been in circulation in similar if smaller publications for eight years, and it had been even more years since the CPUSA possessed any significant political influence in the United States, especially in the states of the Solid South.5 In countless public appearances, writings, and interviews King had rejected the charges that Communists were directing the movement for civil rights or that he espoused Communism. Less than a year earlier, he spoke in some detail on the television program Face the Nation about his objections to the Communist attitude on politics. He went on to criticize FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover by name for allowing his agency to “aid and abet the racists” with conjecture about un-American influence in the campaign for civil rights. A few days after completing the walk to Montgomery, he would appear on the rival show Meet the Press only to be obliged to answer all of the same old questions about the infiltration of Communists into his organization.6 Nothing the ordained Christian minister said could deter opponents to civil rights who were determined to use his stature as a means to characterize the entire anti-racist political struggle in the United States as an incursion engendered by an enemy.7 No matter its actual disposition, black political agency was painted Red by those who mistook the Cold War emergency as an opportunity to translate Southern support for segregation into a security concern the entire nation ought to share.

In this chapter, I take up the JBS billboard campaign to exemplify the discourse of anticommunism as it bears on the black freedom struggle in the United States during the early years of the Cold War. Rehearsing the history of the sign with particular attention to its intertextual composition, I provide an account of how Red Scare rhetoric was employed in support of the massive resistance to civil rights. King’s numerous responses to the charge of Communist and his own appropriation of Cold War insecurities show, however, that anticommunist discourse was ultimately more compelling for the cause of desegregation than for unabashed white supremacy, a point I demonstrate with a discussion of the address King delivered over Labor Day weekend in 1957 to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee.8 That celebration is the occasion the billboard alleges is a class for Communists.

Although my account of King’s anticommunist rhetoric indicates he was able to exploit the same national security anxieties that animate the JBS billboard against him, I also show success harnessing anticommunism for the sake of civil rights came at a price for black freedom struggles in the United States during the long decade of the 1950s. Inviting talk of legal reforms that could encourage an international audience to affiliate the United States with the expansion of democratic franchise across racial divisions, Cold War anticommunism also removed from public culture reasonable deliberation over radical social change, especially in regard to demands justified by criticism of how disparities endemic to capitalism secure the correlation between socioeconomic stratification and racial identities. As King discovered for himself when he became an outspoken opponent of US military actions in Vietnam and went so far as to link capitalism to racism globally, Cold War anticommunism was a potent rhetorical resource for the exercise of agency on behalf of desegregation provided aspirations for equal rights did not entail an appraisal of how the official policy of anti-racism touted by the US Department of State obscured the ways postwar US imperialism was perpetuating the value of whiteness in the geopolitical order.9 Any such rebuke to the normative stories of Cold War America was met with the immediate reprisal of association with the appealingly reductive moniker un-American, a characterization that rendered illegible the particular content and merit of the critique. For example, from within the confines of US public culture the conviction of black radicalism that the US attitude toward the Cold War would likely result in the failure of decolonization and the emergence of neocolonialism in its stead would not just go unheeded; it would remain unheard. My interest in juxtaposing King’s talk at Highlander and his anti-war Riverside speech a decade later is to suggest how the early speech participates in a massive social pedagogy of Cold War anticommunism that in the long 1950s prepared public culture to accept with certainty a tendentious body of knowledge about communism, the Cold War, American national identity, the civil rights movement, and Western modernity as a history of emancipation. This popular “curriculum” of anticommunism meant the public was unready a decade later to acknowledge the merits of King’s revisionist characterizations of capitalism, neocolonialism, postwar US imperialism, the black freedom struggle, and Western modernity as a history of racialization. King’s delivery at Riverside was, in a word, uneasy.

An additional objective of this chapter is to elaborate on the practice of cultural rhetoric studies within my home discipline of literature. To this end, I am concerned with how a strong claim that rhetoric is epistemic informs an examination of normative discursive formations through the interpretation of particular features of language that are conventionally privileged by literary studies: figurative language and narrative. More specifically, I demonstrate how the JBS billboard campaign and related texts, including the two speeches by King, invite and reward an interpretation that negotiates between an emphasis on the rhetorical power of popular tropes and a focus on the pervasive influence of cultural narratives.10 Reconstructing the cultural conversation of Cold War anticommunism, I suggest how the proliferation of Red Scare rhetoric in US public culture during the long 1950s was a pedagogy, in and out of schools, to make citizens expert in a social fiction of the Cold War: a narrative of sufficient normative force to train public culture to neglect, discount, or assimilate rival accounts of social reality.

Popular Tropes and cultural Narratives: Red Scare Intertextuality

The design of the JBS billboard suggests that its photograph is definitive corroboration of well-circulated suspicions that King and the movement he represents take orders from outside America. Although his presence in the image is unmistakable, the arrow pointed at his torso emphasizes his prominent position in an iconic scene of instruction. Attentive postures and the papers on King’s lap encourage this schooling inference. The all-capitals headline above the image has a matter-of-fact pretense that does not name Highlander nor acknowledge that the charge of Communist never amounted to more than a pejorative metaphor for the liberal school. Several nonverbal features of the composition carry further connotations of popular beliefs about the Communist Party. The cropping low above the heads of the assembly implies an atmosphere of secrecy, and the omission of any information indicating the time and place of the proceedings adds the impression that such training could take place nearby or as far away as Cuba, the Soviet Union, or Brooklyn. Just outside the left frame, an invisible authority figure commands attention; what un-American plans might have issued from such a source before they became famous names for social protest: the Montgomery bus boycott, the march on Washington, Freedom Summer? Counting on King’s famous identity to serve as synecdoche for the whole, ongoing story of racial agitation fomented between the civil rights movement and the massive white supremacist resistance to it, the JBS display invites observers to consider how images of racial strife they were likely to have seen in newspapers and on television (if not in person) should be perceived as incidents of the Cold War. To see deeply into the conflict over racial equality, the sign suggests, is to recognize that the antagonism between black and white Americans is actually a proxy for the conflict between Red insurrectionists and free patriots marshaled in support of the American way.

The image of an illicit school to prepare the civil rights movement for Communist objectives suggests that American values are secretly anathema to King and others in the picture who must have dispersed after the gathering to infiltrate the lives of unwitting ordinary citizens. That impression cautions credulous observers to be vigilant about aliens in their midst, and the composition of the classroom with its crowded, interracial mix of men and women seated in close quarters implies that the Communists have also been recruiting. Apparently, the foreign presence is familiar enough to convert citizens to its cause. And for all the individual distinction on display in the diverse assembly, the headline emphasizes symbolically that a single, barely discernible attribute binds together everyone in the picture. I say barely discernible because, though being a Communist did not correspond to racial or ethnic identities that are typically associated to some extent with appearance, anticommunist propaganda from agencies such as HUAC, popular films and television, school curricula, as well as mainstream journalism in the first years of the Cold War reported on how to tell if a person is a Communist—how to read the signs. Involvement in racial causes and, more damaging, interracial personal relationships were high on the profile of characteristics inviting suspicion that a person is loyal to Communist interests and actively un-American.11 With its strategic paucity of verbal detail, the billboard gives no indication that the only person pictured who was known to be a member of the CPUSA is Abner Berry. Seated in the left foreground with his head down over his notes, Berry covered the Highlander Folk School anniversary weekend for the Daily Worker. He was one of two journalists who had asked permission to be present for the event, though he did not acknowledge to Highlander’s director Myles Horton that he was a party member.12 The other journalist took the picture, but he was only pretending to be a freelance documentary filmmaker and photographer. In fact, he was working for the Georgia Commission on Education under the direction of Governor Marvin Griffin, who sought to interfere with the implementation of school desegregation by incriminating institutions and people involved in the advance of civil rights. Another telling omission in the billboard’s intelligent design is any mention of Rosa Parks, who appears in the front row four seats to King’s right. By 1965 her legendary reputation for refusing to surrender her seat at the end of an exhausting workday did not lend itself readily to an accusation of un-American values. Failing to indicate Parks in the crowded room, the sign does the symbolic work of distracting us from recognizing the presence of an iconic figure whose famous refusal to observe a racist law and relinquish her seat on a Montgomery bus was bound up in seemingly apolitical ideas of a respectable woman’s personal frustration dignified by the fatigue of a hard day’s work. Among segregationists, King’s vocation as a minister afforded him no comparable respect. White supremacists in the Jim Crow South also claimed the Bible to sanctify their cause.

The visual and verbal rhetoric indicating, on the one hand, that King and other Communists are studiously un-American and, on the other, that the party holds a dangerous appeal for other Americans, follows the tendency in postwar Red Scare rhetoric to depoliticize the ideas of communism by rendering them alien and yet to task citizens with adopting an anticommunist sensibility that is ever mindful of the risk of unwittingly lapsing into un-American attitudes. The supposed reward of vigilance is to discern in the signs of communism how its desire for social control emanates not from reasoned convictions but from indeterminate, unholy compulsions. This argument against communism as a vicious, unthinking predilection was instrumental for the broader consequence of discrediting all manner of leftist and many liberal ideas for being not political thought but instead aberrant feelings, destructive impulses, or even expressions of monstrosity. Impugning even unwitting resemblance to communism as un-American, anticommunist discourse limited legitimate political ideas to the presupposed “values of the free market, private property, and the autonomous individual.”13 Christianity was also a fairly constant point of distinction from godless communism. Communist critiques of the capitalist tenets of the free market and possessive individualism only helped elevate these ideas beyond reproach, which in circular turn made any kind of complaint about them enough like communism to warrant rebuke.

Countless documents from the early years of the Cold War that advise US government agencies or the general public about the dangers of Soviet Communism in America are rife with tropes for the illicit nature of Communists’ motivations. Attention to such figures has become a staple of American Studies scholarship that examines how the culture of Cold War anticommunism textualized social life in the postwar United States, giving it the impression of a secret population of foreign insurrectionists living in the guise of citizens who beneath their studiously ordinary appearances were apoplectic with un-American seething.14 Accounts of various pejorative metaphors teach how Communists and unrepentant former Communists were made to appear substantially “other” than ordinary Americans and how the lexicon to describe their differences was also put to work as a rubric to identify Communists and fellow travelers hiding amidst unsuspecting Americans. This Cold War epistemology predicated on the simple identification of Communists and non-Communists receives its most famous, perhaps satirical depiction in the film Invasion of the Body Snatchers. The alien “pod people” seem identical to ordinary US citizens unless you can get them talking about the deficiencies of human emotion, the hazards of individualism, the efficiencies of parasitism, and the pleasures of monotonous, hive-minded uniformity. The acute individualism of the film’s protagonist alerts him that imposters have supplanted the good people of his small town. In the actual storyworld of the Cold War United States, various volunteer, commercial, and government institutions guided US citizens to employ tropes as a measure for signs of Communist intent and the sympathy of their fellow travellers.

The allegorical rendering of the Red Scare in the popular genre of a science fiction film about alien life forms arrived to colonize Earth and take bodily possession of all its inhabitants assuredly exaggerates the plot of the Cold War to sensational effect, but the characterization of the mentality of alien enemies compulsively enacting the requirements of their form of life resonates with the hyperbole of statements on Communists by government officials and elite political pundits who were instrumental in both the domestic investigations of un-American activities and the US foreign policy of containment. The public service film What Is Communism? from 1963 is a typical example.15 It asserts that Communists are a “lying, dirty, shrewd, godless, murderous, determined, interna...