![]()

CHAPTER 1

Lessons in Practical Segregation

JOE PATTERSON’S EARLY LIFE AND CAREER LAID THE FOUNDATIONS FOR his future in public life and for his political philosophy. Much like the reality that white southerners had resisted black advancement with every means possible, including outright violence, from the moment that African Americans began exercising their rights of citizenship after emancipation, those white southerners disagreed over the best means of doing so long before Mississippi Senator James Eastland issued the Southern Manifesto in response to the US Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. The conflict between Joe Patterson and Ross Barnett in the 1960s mirrored in many ways the conflict between Theodore Bilbo and Pat Harrison in the US Senate in the 1930s. The fact that, in 1936, Patterson went to work for Harrison, then, explains some of Patterson’s perspective and desire to stay above the unbending, racist fray. Not that Patterson wanted to challenge the Jim Crow norm; he just believed that there were better ways of doing so than those that Barnett and the Citizens’ Council espoused. Even before his time working for Harrison in Washington, DC, though, Patterson found that his childhood and family informed his future personal and political outlook.

Born in Eupora, Mississippi, on July 10, 1907, Joe Turner Patterson grew up with two sisters and two brothers—Tom, Nancy, Doug, and Harpole—in the state’s northern hills, where his family on both sides went back several generations. In fact, Joe’s great-grandfather, William Tryon Patterson, had moved to the Calhoun County area from North Carolina in the mid-nineteenth century. Joe’s mother, Mae Vivian Harpole, was one of ten children raised in a well-to-do family in Eupora. Her parents, affectionately known as Pappy and Granny, ran a general merchant store, which did well enough to allow them the luxury of sending their daughter to the Mississippi State College for Women (MSCW) in Columbus—the first state-sponsored women’s college in the nation.1

Married at the age of eighteen, Mae Vivian stayed at home to raise the children per the gender norms of the day for women of her race and class, and she was the disciplinarian of the family although she was five years younger than her husband, Albert Thomas “Abb” Patterson. Abb had been born in the Calhoun County seat of Pittsboro, just north of Eupora, but his dad—Father Patterson, as he was known by his grandchildren—soon moved the family to Calhoun City, five miles away, and into a two-story house that he had had built on the town square. An “old, staunch southern gentleman [who] … ruled the roost,” Father Patterson served as mayor of Calhoun City for twelve years.2 There, the Patterson family established deep roots.

A country lawyer in the hills, Abb started his practice and began raising his family in Mae Vivian’s hometown of Eupora. He never took the time to learn how to drive, so he depended on his wife to take him to court and anywhere else he needed to go on business. Thanks to his family responsibilities, Abb got a draft deferment during World War I and, soon thereafter, moved his wife and children back to Calhoun City. Their family house was “a great big white-framed home. It had a hospitality porch acros the front that was eventually screened in with big ceiling fans.” The economy of Calhoun City revolved around stores and service stations. If you did not work in town, then you practiced subsistence farming to support your family and planted a small patch of cotton to make some extra money. This was not the Mississippi Delta with its huge cotton plantations. Without any farmland, Abb spent his entire career providing legal advice for the small town, accepting chickens, collard greens, tomatoes, and other homemade goods and produce for his services.3

After he opened his law office in Calhoun City, Abb was elected the county’s district attorney—a position he held until 1952—and served as a chancery court judge for a territory that stretched nearly to Tennessee. From watching Father Patterson and Abb, Joe was “not only educationally but practically schooled in how government worked.”4 Joe implemented these lessons in his own life and career as he climbed Mississippi’s political ranks and faced the task of propping up Jim Crow while it started to fall around him.

On retainer with the Illinois Central Railroad—perhaps due to some success he had had in suing the railroads—Abb Patterson had enough money to pay the bills. That fact alone made him and his family hill country aristocracy in relation to the rest of the community. Joe’s sister Nancy remembered that “we didn’t have whole lots of money, but we had a home…. We had about as much as anybody else because in a little, small town no one had a large amount of money, but we got along just fine.” Named after J. T. Dunn, a fourth district Circuit Court judge, Joe was the oldest, and he idolized and developed a close relationship with his father. Like his dad, Joe was “very calm, not a flustered type of person,” but he was quite serious as well. According to his other sister, Doug, “Joe was born a little old man.” Joe never left “the house unless he was dressed very, very appropriately … but we were reared that way.”5 Abb imparted lessons about what he saw as the appropriate race, class, and gender roles for his children.

Joe’s sister pointed out that Abb “loved his boys, but he thought his girls should be shielded, taken very good care of, so that was the way we were reared: old southern style.” In addition to reinforcing Victorian-era gender norms, that “old southern style” included having a domestic servant, “A black in your backyard … at our beck and call. We wanted a dress pressed in the afternoon to wear to town; if she was out in the backyard, we would call her, and she’d come press our dress.” They even “had a house in the backyard” where the maid lived. “We never did have any trouble finding anybody because my daddy said we respected whoever was working. They had feelings.” If anyone said anything with racist undertones to the maid or other local blacks, Abb corrected them—another habit Joe acquired. At Christmas, Abb invited the maid into the house to participate in the festivities, especially with the “Christmas tree…. The girl that was working for us came to the Christmas tree.”6 This type of supposedly benevolent paternalism maintained demarcated lines of power and propriety when it came to race relations.

As Nancy recalled, Abb’s paternalism extended to the families of both white and black soldiers during World War II. Specifically, Abb helped black women get their fair share of wartime allotments. When asked about his fees, he replied: “‘I don’t charge anybody…. Anybody’s got a loved one in the service I don’t charge them anything.’”7 Abb’s reputation established his standing in the community and set his family apart from and notably above that community.

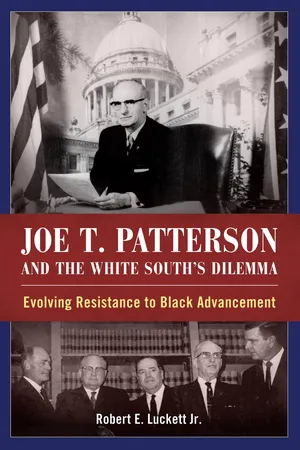

Joe grew up to be as respected as his dad in Calhoun City, and he was as well versed in the “tradition of the southern orators” with a distinctive, slow drawl, rooted in his Mississippi lineage. With a receding hairline, high Patterson forehead, sunken eyes, square chin, and skinny frame, he was not an imposing figure, but he commanded deference. Patterson was not an animated speaker in the mold of southern preachers and political demagogues. He neither flailed his arms and legs nor screamed racial epithets. Instead, his calmness leant an unmistakable seriousness to his demeanor. An unassuming man, he did not avoid the spotlight but did not seek it either. That style became his political calling card and a key part of his strategy for offsetting the advances of the modern civil rights movement.8 He did his job in a consistent, low-key, and dedicated manner that was marked by an unflagging commitment to Jim Crow laws even as they were legally crumbling.

As a boy, Joe memorized poetry in his free time and kept a collection of verses about life and death. He had been educated at a time of rote learning and “the ‘Great Book’ method of education,” which included the memorization and recitation of poetry and the classics. In 1965, Patterson testified before a US Senate subcommittee looking into the implementation of the then-proposed Voting Rights Act. When asked how the 1964 Civil Rights Act had affected the Deep South, he referred to the US Justice Department and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy in less than flattering tones with quotes from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. Never a fan of Robert Kennedy, Patterson added the verses off the top of his head; they were not a part of his planned testimony. It was all “part of that classical training. He could quote poetry, English Romantic poetry, sitting at a dinner table.”9 In nearly all of his public speeches, he added scripture, poetry, and song.

After graduating high school at the age of seventeen, Joe briefly attended Mississippi A&M (now Mississippi State University) before transferring to Mississippi College in Jackson for about a year and half. Finally, he came home and worked for a short period in his cousin’s drugstore and then at the Grenada Bank in Calhoun City. Not satisfied, he left on the train less than a year later to attend Cumberland University Law School in Lebanon, Tennessee. By 1929, Joe had an L.L.B. from Cumberland and was set to return to Calhoun City.10 After being admitted to the Mississippi Bar that same year, he came home and created what in most people’s minds was a long-awaited law partnership with his father.

Joe and Abb’s business relationship, as opposed to their personal one, was rocky. They shared an upstairs office in a warehouse north of the square in Calhoun City, where Abb had established a regular clientele. In fact, everyone in Calhoun County knew Joe’s dad, and most just called him Uncle Abb. They also knew that he would do their legal work for free if they called him Uncle Abb, and many people showed up at his house on Sunday mornings to do business on the front porch. Once Joe was back in Calhoun City working with his dad, people walked past Joe. They knew that he was going to bill them, so they went straight to Abb. One day, Joe got fed up and told his father that he was not going to watch those people pass him by in order to get free legal services from Abb. “That’s when he made up his mind he was not going to stay in Calhoun City.”11 His way out was politics.

Less than a year after returning to Calhoun City, Joe was elected city attorney as a Democrat. Of course, the entire family had been traditional southern Democrats, descendants of the racist white Redeemers who ended the high promise of black political participation in the South during Reconstruction through the subsequent invention of Jim Crow disfranchisement. But Joe made some important distinctions in his early career. As opposed to many in the state Democratic Party, Joe worked against the Dixiecrat movement of Strom Thurmond in 1948 as well as the “Eisencrat” movement of southern Democrats voting for Dwight Eisenhower in 1952.12 More than anything, those stands were practical decisions in the name of more power in national circles at a time when African Americans posed little threat, but they foreshadowed Patterson’s future decisions to break with the Citizens’ Council and the likes of Ross Barnett in the 1960s.

After a short stint as city attorney, Joe decided to run for a seat in the Mississippi House of Representatives in order to gain name recognition, and to his surprise at the age of twenty-six, he defeated the incumbent for the first of two stints in that office. Although he spent a lot of his time in Jackson, Joe remained close to his dad and came home as often as possible to talk to him.13 Joe’s political prospects were high, and despite his commitment to his family and his constituency, he was ambitious and anxious to get out of Calhoun City.

In 1936, four years after being elected to the state House of Representatives, Patterson took a job as chief legislative assistant for US senator Pat Harrison. In her biography of Harrison, historian Martha Swain describes him as “a quintessential conservative” and model southern Democrat for the 1930s. “One of the patriarchs of the United States Senate,” Harrison first won election to the US House of Representatives in 1913, but five years later, he was promoted to the Senate. As chairman of the Senate Committee on Finance during the New Deal, Harrison wielded a lot of power even as he waded through the “rough and tumble” era of James K. Vardaman and Theodore Bilbo, whose vitriolic racism marked those days as one of high factionalism in Mississippi. Harrison proved to be “the most formidable rival both Vardaman and Bilbo would face” in the course of their Senate careers.14 Those divisions between Harrison and the standard-bearers for racist demagoguery were not rooted in a disagreement over white supremacy or black oppression but over the means to preserve that supremacy, something that informed much of Joe Patterson’s future political and social outlook.

Harrison announced his desire to challenge the incumbent Vardaman for his US Senate seat in Philadelphia, Mississippi, at the 1917 Neshoba County Fair, the Fair being a mainstay well into the twenty-first century for stump-speaking politicians. Harrison campaigned on a pro–World War I, pro–Woodrow Wilson platform, which stood in stark contrast to Vardaman’s race-baiting, anti–World War I, and anti–Wilsonian strategy. Because Harrison “rarely addressed himself to domestic issues,” he avoided the topic of race and racism, but his foreign policy positions proved popular in the election. When an overconfident Vardaman did not return to campaign in Mississippi, Harrison easily won the Democratic primary, ensuring his victory during the general election as white Democrats controlled statewide politics.15 Harrison’s election did not signal the rise of a racially egalitarian white leader, and his silence on domestic issues did not mean that he was ignoring racial issues.

Harrison’s personal papers indicate that he was paying close attention to race early in his national political career, and not surprisingly, his constituents would not let him altogether avoid it. In fact, Harrison kept articles, essays, and stories about race throughout the 1910s and 1920s. For instance, he saved an article written by President William Howard Taft in the Washington Post. Taft, a Republican, was addressing the race riots throughout the country that had branded the summer of 1919 as Red Summer.16

For Martha Swain, Harrison was no racial progressive because “he was too bound by his belief in states’ rights.” Of course, states’ rights had been the mantra of white southerners since before the Civil War. It was a thinly veiled racist argument, meant to keep the federal government out of the business of the white South, particularly when it came to race and social and political institutions ranging from slavery to Jim Crow and lynching. It was a way to make racist arguments without mentioning race, a strategy that Joe Patterson took to heart. For instance, Harrison opposed federal adult literacy programs because, in Swain’s words, they infringed “upon the right of local communities to conduct their own educational affairs,” but Harrison would have recognized the probable impact on black illiteracy and subsequently on white power.17 By not engaging a racist dialogue like Vardaman and Bilbo, Harrison came to wield much more power within the Democratic Party on a national level and could support his voters at home while maintaining white supremacy.

In the context of the stringent dedication to Jim Crow in the South during his tenure, Harrison avoided the sticky issues of race by claiming that they were not the business of the Senate. At the same time, he could preserve white power by not stoking a firestorm that might force the federal government into action. Of course, Harrison’s power as a US senator from Mississippi was based on Jim Crow disfranchisement, so he had a vested interest in being informed, but he realized that by not engaging a public, racist dialogue over a topic that was not part of the Senate’s agenda, he could grow his power nationally and better support his white constituents at home. In a handful of instances, Harrison was forced to make minor concessions in facing his racist politics, but on those few occasions, he extricated himself without causing any damage to his political career.18 The Great Depression and the rise of Franklin Delano Ro...