CHAPTER 1

BUILDING A SOCIALIST HOME BEFITTING THE SPACE AGE

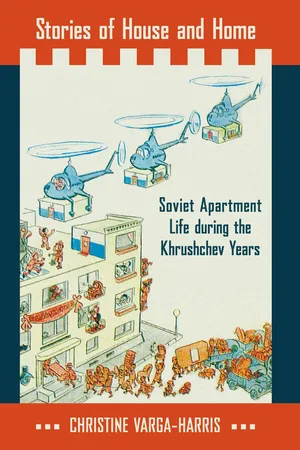

THE YEAR 1957 was an extraordinary one for the Soviet Union, ushering in the launch of both Sputnik, the first artificial space satellite to orbit the earth, and what Blair Ruble characterized as “perhaps the most ambitious governmental housing program in human history.”1 Soon afterward, the country was forging ahead in the cosmos, boasting the first man in space—Yuri Gagarin in 1961, and then the first woman to orbit the earth—Valentina Tereshkova in 1963. Like the Soviet space program, the housing campaign produced striking results, providing almost 300 million citizens about 70 million apartments by the late 1980s.2

Plodding along amid the spectacular technological achievements of the global space race, however, domestic construction may have appeared less dramatic at the time. While appreciating how greatly Moscow had changed during the five years since his last visit, the US journalist Harrison Salisbury noted in 1959 that those who had been present during the transformation were less affected “because they had seen it all happen piecemeal.”3 Yet throughout the 1950s and 1960s, in official and literary discourse alike, progress in mass housing provision was associated with the dawn of the radiant future as much as the inauguration of the exploration of the cosmos, and it too was rendered worthy of awe.4 This is richly conveyed in the 1960 novel Dorogi, kotorye my vybiraem (The paths we choose). In one particular scene, the protagonist Andrei expresses wonderment with the southwestern district of Moscow, as he is seeing it for the first time after a long absence from the capital. Standing before a leading experimental construction site, this resolute worker finds himself in “a somehow strange, unfamiliar being-built world.” He had seen housing being built before, but never with such speed. Here apartment houses appeared to be miraculously “arising out of the earth.” The absence of old inhabited buildings nearby heightened the impression that “everything was in motion,” as did the frenzy of construction itself. Andrei states,

everywhere around me rays of powerful searchlights aimed below were digging out of the darkness first the corner of a multistory building not yet faced with tiling, with hollow window holes, then a bottomless pit; at one moment a pile of brick, at another, roaring lines of lorries…. Dazzlingly bright flashes of electric welding arose, first above, then below, to the right, to the left of me.

The protagonist is so captivated by “the grandiose scale of construction unfolding all around” him that, ironically, he finds himself “standing motionless.”5

The focus of this fictional passage on the act of building, rather than on the finished product of a smartly designed apartment house, corresponds to a major shift in housing policy that occurred during the Thaw: architecture was effectively reduced to being “the unfortunate handmaiden to the construction industry,” as Stephen Bittner succinctly stated.6 The confrontation between architectural design and construction occurred at the November 1954 All-Union Conference of Builders. On this occasion, just a few years prior to assuming leadership of the country, Khrushchev publicly rebuked architects for being preoccupied with producing “fine silhouettes”—which required more resources and time to construct than simple ones—and inattentive to ordinary people, who “need homes” and “want to live in buildings.”7 Still more damaging, architects were purged and the Academy of Architecture was renamed the Academy of Construction and Architecture, symbolically demoting their profession.8

The construction industry was also subjected to criticism. The intention in this case, however, was to stimulate innovation in engineering, technology, building materials, production, and labor organization.9 Nevertheless, with housing provision bound to the same mechanisms of the command system as other sectors of the economy, the central authorities were in charge: the Communist Party, the Supreme Soviet and the Council of Ministers of the USSR provided the directives, finances, and supervision for architectural design, construction, and urban planning throughout the Soviet Union, while the Academy of Construction and Architecture was summoned to implement the resolutions that these bodies made.10

Where housing development was concerned, members of the Academy were responsible for practical matters like the industrialization, standardization, mechanization, and organization of construction; the planning and equipping of living space (from basic amenities to furnishing); and the expansion of consumer services and cultural establishments in housing blocks.11 Ordered to shed the extravagances that had characterized the monumental neoclassical buildings of the Stalin era, architects were expected to conform to the demand that Soviet housing be bright, clear, and simple. The matter of how, precisely, new housing was to manifest these qualities is one subject of this chapter. Significantly, plainness could facilitate another official objective related to dispensing with “fine silhouettes”: building faster, better, and more economically. Toward this end, the architectural profession was charged with harnessing the ingenuity of the building trades. Recognizing this mandate in the context of the broader technological advances of his day, one architect proclaimed it his duty “to work out the artistic principles corresponding with the technical peculiarities of the Twentieth Century—a century of atomic energy, space ships, automation and electronics.”12

Even as industrial methods appeared to be eclipsing creative ambitions, architects, artists, engineers, and urban planners—operating under directives issued by the state and Party—assumed a vital task. Collectively comprising a cohort of “aesthetic experts or taste professionals,” it was their role to realize the potential of new construction to restructure daily life.13 After all, the modern, separate apartment was not intended to constitute an end in itself; it was supposed to reflect socialism as it was becoming and to make daily living socialist. Thus, experts expended an enormous amount of energy synchronizing the various elements of the domestic sphere with contiguous spaces like building courtyards. Intent on integrating craftsmanship and technology, and art and utility, professionals in the fields of architecture, art, engineering, and urban planning generated a barrage of prescriptive literature, as well as conceptualized and critiqued exhibitions and provided lecture series.14

Also undertaken in the design realm was the ideological aim of conjoining the individual family dwelling with the collective ideals on which the Soviet Union was founded. At issue was harmonizing private and social interests to render an aesthetic with strong parallels in the West, representative of the communist society that was emerging. Indeed the traits of housing design that were so prevalent in the architecture of the Thaw were not unique to the Soviet Union. Following a tradition of appropriating concepts from abroad, architects under Khrushchev discussed North American and European models at length.15 For instance, the notion that form should follow function, central to Soviet housing design during this period, had dominated the thinking of earlier Western architects like the American Louis Sullivan, and the Swiss-French Le Corbusier, whose first large commission was in Moscow in the 1920s. Soviet architects during the Thaw also esteemed the US architect Frank Lloyd Wright, and implemented several of his signature elements. These included the use of reinforced concrete; the harmonization of internal spaces, as well as of interiors with the natural landscape; a striving for a sense of openness; and the conformity of form to function in terms of structure, furnishing, and décor.16 Even stylistic references from Russian tradition, namely 1920s Constructivism, were often imported from the West during the Thaw, “projected back at Soviet architects” after decades of official disfavor within the Soviet Union.17

The circumstances of the postwar era too played a role in determining Soviet construction methods and design. In particular, the “new” architecture under Khrushchev—simple and functional—had provided an inexpensive way to hasten reconstruction throughout war-torn Europe, suited as it was to mass production. Appropriating straightforward and practical furniture designs from the West was also determined by pragmatism, given the task Soviet architects shared with European ones after World War II—“to struggle, literally, for centimeters of free space” in the face of a severe housing shortage.18 It is in this spirit that an article in the trade publication of the Union of Artists, Dekorativnoe iskusstvo SSSR (Decorative arts of the USSR), featured practical tables of French design, together with illustrations reproduced from a Parisian home furnishings magazine. Described as affixed to the wall and measuring about one square meter in dimension, these tables were lauded for taking up a minimal amount of space, something that made them particularly suitable for small apartments. Presenting them as attractive as well as functional, the commentator noted that these tables could fold out to create a space for children to complete their homework or a dinner table for up to eight people, and with their plastic surface, adequately serve “decorative purposes” as well.19

Alongside the vision of light, spacious, functional, and comfortable dwelling that came to be associated with the Khrushchev period, the propensity toward plotting out each and every variable considered necessary for realizing the living concepts that underpinned housing policy was also not unique.20 Commenting on the postwar interior in general, Witold Rybczynski asserted, “A modern building was a total experience; not only the interior layout but also the finishing materials, the furnishings, the accessories, and the location of chairs were planned.”21 In accordance with this trend, Soviet architects presented furniture and decorative appointments as essential for creating an efficient and attractive environment within the new apartment. They approached the production and distribution of domestic wares and household appliances as crucial to the ultimate success of housing policy.22

Although the modern composition of the Soviet built environment implied a degree of postwar universality, its interior was designed to express a distinct temperament. Remarking on the characteristics of household objects, one Soviet expert acknowledged that like other items of furnishing and decoration, in terms of function or dimensions a chair is a chair, regardless of where it is manufactured. Yet, he asserted, the structure and values of a given society can be intimated through “all these things organizing daily life.” For example, the “relatively large quantity of spaces for studies” and “many book shelves” being incorporated into new apartments in the Soviet Union, he claimed, were testimony to the high literacy rate in the country.23 He thus declared, “The contemporary interior…is the direct result, the concrete, material expression of the social order of the Soviet people.”24

More was at stake than building homes faster, better, and more economically with modern industrialized construction methods (solving the housing shortage) or supplying bright, simple, and efficient interiors (completing the transition to contemporary one-family living). “Khrushchev modern” signified grand transformations in both the form and meaning of Soviet dwelling.25 Thus, although the harassment of architects surrounding the 1954 Conference of Builders appeared to indicate the continuation of authoritarian tendencies in political culture, the design trends that developed in its aftermath were antithetical to those of the Stalin era.26

Two additional caveats should be made. First, the impulse to produce modern and functional housing was not absent among individual architects.27 Second, the Thaw enabled architects to reassert their status and appropriate from Stalinist bureaucrats the traditional prerogative of intellectuals to define cultural standards in the name of “the people” by extending their influence over the “aesthetics of everyday life” as part of a cohort of design professionals.28 The transformation of the Soviet home was intertwined not only with the Cold War competition signaled by the launch of Sputnik, but also by de-Stalinization.

Building the Housing Ensemble—“Faster, Better and More Economically”

In a celebratory moment that represents a tribute to new housing constructi...