![]()

1

Introduction

Another world is not only possible; she is on her way. On a quiet day I can hear her breathing.

Arundhati Roy

One’s destination is never a place, but a new way of looking at things.

Henry Miller

Hearken not to the voice, which petulantly tells you that the form of government recommended is impossible to accomplish.

James Madison, The Federalist, No. 14

Objectives

Global problems require global solutions. This dictum provides the motive for writing this book. The idea ought to be self-evident, but clearly is not. Our present system of global governance – if one can call anarchy a system – shows little evidence that the principal actors on the global stage have come to grips with the magnitude of the existential threats to a sustainable civilization. The world has thus far failed to put in place a set of agencies suitably empowered to deal with such long-standing threats as the war system and more recent threats, especially those posed by climate change and other forms of environmental degradation. Existing institutions, within and outside the UN system, must be strengthened and given broader mandates, and new agents of change must be created. The decisions they make must be recognized as legitimate. Time is short. Fundamental reforms in the near future are essential.

A simple, but key, premise underlying this work is that the design of decision-making institutions has an important bearing on the quality and legitimacy of the decisions they make. To the extent that this simple truth is recognized, society will be inclined to endow vital institutions with greater responsibility and provide them with greater resources. From this it follows that improved designs for existing institutions and, where needed, the creation of new, well-designed institutions can set in motion a virtuous cycle that will contribute significantly to the evolution of a more workable world.

The workable world that I envisage centres on a revitalized and substantially strengthened UN system. While many of the essential institutions within that system are already in place, none is optimally constituted. In particular, their methods of allocating decision-making power bear little relationship to the actual power of global actors outside the arena of the UN itself. Consequently, their fairness and even their legitimacy are often called into question. Moreover, some institutions needed for an efficiently working UN system have yet to be created. Other agencies that have become obsolete or have failed to live up to the hopes and expectations of their creators should be eliminated. Finally, the entire system suffers from a serious democratic deficit. Institutions are needed by which to engage ordinary world citizens and civil society organizations in the work of global governance.

Among the multitude of existing and proposed components of the UN system that call for critical scrutiny, this work pays particular attention to the Security Council, the General Assembly, an Economic, Social and Environmental Council (to replace what is now the Economic and Social Council), a strengthened Human Rights Council (to replace the moribund Trusteeship Council), an eventual World Parliamentary Assembly, new civil society coordination councils and a standing UN Peace Corps. Other essential institutions, such as the International Court of Justice and International Criminal Court, will be more cursorily examined. Their chief shortcomings are not questions of design, but rather of neglect. Ways have to be found to ensure that they are used to a much greater extent than they have been to date.

While I will devote relatively little attention to the working methods – as opposed to the structure – of agencies within the UN system, several especially important functions do call for special scrutiny. These include fundraising and budgeting; recruitment and promotion of Secretariat staff; monitoring compliance with global laws, norms and standards; conflict resolution; administering failed and failing states; and integrating civil society and responsible entities within the corporate sector into the ongoing work of the United Nations.

Apart from my general advocacy of inclusiveness and fairness in the way decisions are made, this book is not about specific policies that the United Nations or its various affiliated agencies and programmes should follow. I am confident that reform of the decision-making processes will provide an adequate basis for forging wise and workable decisions and correcting mistakes that will, inevitably, be made from time to time.

Although my proposals are idealistic in conception, there is nothing utopian in what I shall be presenting. I do not foresee a world free from conflict, but rather one in which international warfare will become as inconceivable as war now is between member states within the United States or, for that matter, between member nations within the European Union. In such a world, conflict will be managed or contained with a minimum of violence, a maximum of reason and an acceptable degree of constructive UN engagement.

Nor do I envisage a world free from economic want and serious social and environmental stress. But I am convinced that humankind can, in as little as one or two generations, achieve and greatly surpass the well-publicized, but inadequately supported, Millennium Development Goals and thereby substantially narrow the obscene gulf separating the world’s haves and have-nots. That achievement will greatly reduce the propensity for domestic violence and international terrorism, and free economic resources now allocated to the ill-conceived “war on terror” for the pursuit of more beneficent ends.

I have no illusions that any of what I shall propose will come about easily. Wealthy and relatively secure nations tend to support the status quo. Within the United Nations, the five permanent, veto-wielding members of the Security Council (the so-called P-5) will be particularly inclined to defend their anachronistic and unfair privileges, a situation derived from their being on the winning side in a war concluded two-thirds of a century ago. This is undoubtedly the greatest single reason why reform of the UN Charter has to date been so difficult and so seldom achieved. Additionally, in the absence of a reformed and strengthened United Nations, the United States in particular has for decades been inclined to rely on unilateralist initiatives or on self-appointed “coalitions of the willing” (under US leadership) to achieve its geopolitical objectives, often in defiance of international law and leading to tragic, even if unintended, consequences.

But medium and small powers are also inclined to pursue parochial and short-term interests. They too tend to resist any infringements on their precious sovereignty. Their leaders often fail to realize that promoting the good of the whole will generally also, in the long run, serve the good of their own nation. Nor would many acknowledge the remarkable extent to which their sovereignty has already been eroded by a multitude of intrusive forces, many of which may be subsumed under the general heading of “globalization”. In short, vested interests, inertia and ignorance present powerful impediments to the realization of the agenda set forth in this work.

There are other serious problems as well. Greedy, overambitious and despotic leaders continue to bully their way on to the global political stage and stir up trouble in and beyond the areas they control. Serious tensions between cultures and individual nations persist. Severe ethnic and religious strife, mainly intra-national, remains endemic in much of the world. And major changes have emerged within the global ecosystem for which we are far from sufficiently prepared, and over which we will likely have little effective control.

Many problems within our astonishingly diverse and interconnected global society cannot be adequately dealt with by individual nations. Rather, they cry out for some measure of concerted regional and/or global oversight. Such oversight will necessitate the evolution or refinement of norms of international behaviour that not only establish the rights and responsibilities of nations but also codify and guarantee the rights and responsibilities of individual human beings. And individual citizens must be accorded a greater role in shaping their own destiny. The global democracy deficit must be progressively reduced. Our sense of global stewardship must be heightened.

Collectively, society will have to refine and accept fair and sustainable economic and environmental standards. This presupposes the existence of appropriately empowered institutions designed so that their decisions will be seen as legitimate, command broad international respect and receive political backing from the global community. This book discusses a number of such institutions and – in keeping with the dictum that form follows function – it will demonstrate why the designs proposed are appropriate for the functions to be performed.

I make no claim that any of the institutional designs put forward in this book are the only ones capable of promoting the objectives they address, and I recognize that many competing proposals have already been advanced for some of the institutions considered. But the ones presented here are those that I deem most promising, given my inevitably subjective assessments of the problems the institutions will have to address, the political and economic environment in which they will operate and the resources they are likely to command. Other worthy proposals will surely be forthcoming, each with its own pros and cons and likely costs and benefits; and nothing would please me more than to have my own formulations inspire others to advance alternative recommendations and have the merits of their respective ideas seriously debated.

Some of the proposals in this work would require amendment of the UN Charter. Others would not. Oddly, some of the most important proposed changes, for example the creation of an initially advisory World Parliamentary Assembly, would be in the latter category, in that Article 22 of the Charter authorizes the General Assembly to establish such “subsidiary organs” as it deems necessary for the proper performance of its functions. On the other hand, expanding the Security Council by even a single seat would require a Charter amendment. Other proposals might not require Charter amendment but would necessitate reinterpreting that document, as has already happened on numerous occasions, for example in regard to peacekeeping – a word of which the Charter makes no mention.

The timing for action on the changes proposed in this work would be flexible. There is no obviously optimal, much less necessary, sequencing for their adoption. While there are arguments favouring a gradual approach, adopting reforms one at a time, a strong case can also be made, on grounds of synergy, for adopting multiple changes as parts of one or more integrated reform packages. For example, the creation of a UN Peace Corps in tandem with the establishment of a UN Administrative Reserve Corps would give each of those agencies a greater chance of being effective than if either were to be established without the other. There is also the possibility of adopting the proposed reforms by means of a single grand constitutional process, commencing with a comprehensive review conference under the terms of Article 109 of the Charter. All things considered, a relatively gradual, piecemeal approach seems more promising at the outset. But that could well change as trust in the efficacy of a reformed UN system is generated.

Questions of perspective

Many recommendations in this work are predicated on the eventual acceptance of a political paradigm that interprets the term “sovereign equality of nations” quite differently from the way it is presently understood within the UN system. The current increasingly dysfunctional legal fiction in respect to sovereignty, originating with the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia, is enshrined in the “one-nation-one-vote” principle followed in the UN General Assembly and most other UN agencies. However, while nations pay lip service to the principle, they ignore it in practice when doing so suits their purposes and they believe they can do so with impunity. The presumption of equality is, in fact, so glaringly at variance with the perceptions and behaviour of nations outside the arena of the United Nations itself that the disjuncture seriously compromises the credibility and legitimacy of the entire UN system.

Yet the Security Council, the one UN organ whose decisions are meant to be binding, makes a mockery of the pretence of equality. Within the Council, five permanent members wield the veto and are therefore free from the fear that they will be adversely affected by any resolution of which they seriously disapprove. Another 10 elected members enjoy an enhanced diplomatic status, but only for a two-year, non-renewable term. And the 178 remaining nations are effectively denied the franchise. The vaunted sovereign equality principle simply does not apply.

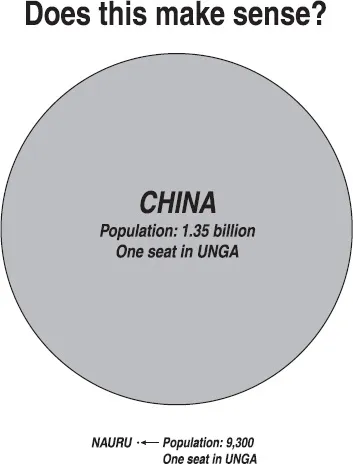

To appreciate the absurdity of this principle as it works in the General Assembly, consider Figure 1.1, comparing the population of China, the UN’s most populous member with roughly 1.35 billion inhabitants, with that of Nauru, the organization’s least populous member, with a population of only 9,300. The ratio between China’s population and that of Nauru is nearly 150,000:1; yet Nauru’s vote is equal to that of China in the General Assembly. And, as we shall see in our discussion of reform of the General Assembly, there are so many other states with small populations (e.g. Tuvalu with 11,000) that it is theoretically possible for 129 nations, with a combined population of only 8 per cent of the world’s total, to command the two-thirds majority needed to win a General Assembly vote on a substantive issue. Even more absurd is the theoretical possibility that 65 nations (one-third of the total membership), with a combined population below 1 per cent of the world total, can block passage of a substantive resolution.

The enormous disparities among nations, however, are not only demographic. They are also evident along other major dimensions: economic, military, performance in respect to human rights, stability of government and so forth. To comprehend this point in economic terms, imagine a graphic comparison of the gross national incomes (GNIs) of the microstate of Tuvalu and the United States similar to the one for population in Figure 1.1. If we were to keep the dot size for Tuvalu the same as that of Nauru in Figure 1.1, we would require a circle nearly four times as large as the one for China to depict properly the ratio between the two GNIs (roughly 560,000:1). Is it any wonder, then, that the UN Charter does not empower the General Assembly to make binding decisions?

While many works on UN reform do note the existence of substantial disparities among nations, most say little or nothing about their actual extent. Readers, then, might understandably assume that they fall within some manageable range and are not much greater than, let us say, the disparities among states within the United States. However, the ratio between the populations of California and Wyoming, the most and least populous states respectively in 2010, is a mere 66:1. This is an altogether different situation than the 145,000:1 ratio between China and Nauru.

Figure 1.1 Comparison of populations of most and least populous UN members

To deal with the disparities and power differentials among nations, sensible decision-making rules should embody some principle of appropriately weighted voting. However, deciding on the most appropriate bases for weighting will depend on the tasks that particular institutions are expected to perform. The institutional designs put forward in this work – in contrast to virtually all others – are predicated on this general functional principle. And the reasoning behind each specific decision will be made explicit. The proposed designs entail simple, objective mathematical formulae, the logic of which derives from the issues they address, with due regard for the often-divergent interests of shareholders and stakeholders within the UN system.

Although the preamble of the UN Charter propounds a number of lofty goals, the primary focus of that document was national security. The drafters of the Charter looked backward for much of their inspiration, and failed to anticipate the profound changes that would occur in the world over ensuing generations. Apart from the differentiations between major powers (the P-5) and other independent states, and between independent states and dependencies, no distinctions among states were made on the basis of population, economic capability, degree of democratic governance or other criteria relevant for effective global governance.

Developments unanticipated by the UN’s founders include the Cold War; the development of nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction; the profound regime changes in mainland China; the collapse of the Soviet Union; the rising fortunes of Japan and Germany relative to those of the United Kingdom, France and Russia, and the even mor...