FEW ISSUES ARE MORE CONTROVERSIAL than immigration.1 The flood of illegal immigrants across U.S. borders enrages many native-born residents who believe that immigrants compete for jobs, unfairly draw on government benefits, and fundamentally alter the social fabric of America. These native-borns fear that non-English-speaking foreigners who move to the United States—legally or illegally—and do not integrate into mainstream social and political life are threatening to erase our culture’s distinctive character.

Part of this anxiety is rooted in ethnocentrism and group animus. People tend not to like others who look or act differently from themselves. As Donald Kinder and Cindy Kam noted in their recent book, ethnocentrism is common in many different societies. People divide themselves into “in-groups and out-groups,” and these types of “us versus them” distinctions color public opinion and make it difficult to develop balanced public policies.2

Others are concerned about immigration because they view the material costs of open-door policies as broad-based but see the benefits as concentrated. As researcher Gary Freeman argued, the impact of open policies falls on disadvantaged workers who feel their wages are depressed by newcomers and on taxpayers who worry about a drain on public resources, while the benefits accrue to small groups of successful immigrants who get good jobs and to some businesses that gain the skills of new arrivals.3

Both ideas (group animosity and unfavorable cost-benefit ratios) make it virtually impossible for the American political system to resolve the many conflicts involving immigration. Many taxpayers feel that immigrants receive more benefits than they deserve and that the social costs of undocumented arrivals are enormous. As long as these are the prevailing citizen interpretations, immigration will remain controversial, many will favor punitive policies, and political leaders will find it impossible to address this topic.4

In this book, I seek to reframe the public debate over immigration policy by arguing that the benefits of immigration are much broader than popularly imagined and the costs are more confined. Despite legitimate fear and anxiety over illegal immigration, I suggest that immigrants bring a “brain gain” of innovation and creativity that outweighs real or imagined costs. Throughout the nation’s history, immigrants have enriched economic, intellectual, social, and cultural life in the United States in a number of fundamental respects.5 The nation needs a new national narrative on immigration that moves from themes of illegality and abuse to innovation and enrichment. The country needs to build a new public policy based on empirical realities, not abstract fears and emotions.

To build a stronger case for immigration, the government needs to make policy changes that promote the benefits of immigration, while simultaneously adopting policies that reduce fears about its social and material costs. Policymakers should expand visa programs that bring talented and entrepreneurial foreigners to the country.6 And the government should take border and employment security seriously to ease citizen concern about the impact of illegal immigrants on national life. These actions will not completely reassure those who oppose immigration based on group animosity or economic impact. But if these policy shifts are adopted, they will help citizens see the virtues of in-migration and make them less anxious about new arrivals.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF IMMIGRATION

From 1820 to 1920 nearly 30 million foreigners arrived in the United States. Close to 400,000 immigrants arrived in 1870 alone; ten years later that figure rose to over 450,000 and remained high for several years.7 These migrants transformed America, supplying labor for the great industrialization that swept over the country. But their presence also ignited sharp divisions over the character and impact of foreign immigration. Indeed, many of the current debates mirror arguments that took place more than 100 years ago.

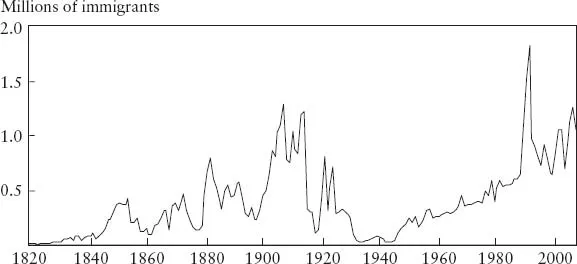

Over the course of the twentieth century, the level of American immigration has fluctuated considerably depending on political and economic circumstances.8 As shown in figure 1-1, in-migration between 1860 and 2007 reached a high point of over 1.2 million individuals in 1907, but then dropped to under 300,000 in 1917 toward the end of World War I. Levels rose again during the 1920s but slowed to a trickle during the Great Depression of the 1930s. In the last few years, levels rose to around 1 million new entries each year. Today, around 13 percent of immigrants are first-generation arrivals, while 11 percent are American-born children of immigrants.9

Early immigrant waves in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries came largely from European stock. These initial migrations gave us our language and people with experience in farming, business, and trade. The Germans arrived in the 1840s and 1850s, seeking land and fortune in the Midwestern part of the country. They were followed by Russians, Irish, and Italians in subsequent decades.10 With this mix of ethnic backgrounds, the image of the “melting pot” became the prevailing metaphor of this time period.

In the mid-twentieth century, though, the main countries of origin shifted south and east. The largest sources of immigration in recent years have been Asia, South and Central America, and Africa. Of the 1,052,415 legal permanent residents who came to America in 2007, 36 percent emigrated from Asia; 32 percent entered from the Caribbean, Central America, or other parts of North America; 11 percent migrated from Europe; 10 percent arrived from South America; and 9 percent came from Africa. The largest single country of origin was Mexico (14.1 percent of all lawful immigrants), followed by China (7.3 percent), the Philippines (6.9 percent), and India (6.2 percent).11

FIGURE 1-1. Number of Lawful Immigrants, 1820–2007

Source: U.S. Dept of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, 2007 (www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/yearbook/2007/table01.xls).

These immigrant waves were very controversial.12 The languages, even the alphabets, of these new arrivals were unfamiliar, and the immigrants themselves were racially and ethnically different from their European predecessors. In many cases their religious, cultural, and political backgrounds differed significantly, and it was harder for them to assimilate.13 Americans did not always accept them as fellow countrymen and women, and their cultural distinctiveness would put the idea of a melting pot to a fundamental test.

The large population movements over the past decades are not just a U.S. phenomenon. In 2008 there were an estimated 191 million “transnational immigrants” and over 30 million political refugees around the world.14 With the advent of civil wars, natural disasters, economic inequality, and relatively cheap air travel, migration has become a growth industry. Indeed, the economies of many developing countries rely heavily on the remittances migrants send home to their families from their earnings abroad. People move not only to gain better economic conditions, but to reunite with families, seek freedom of political expression, or escape poor personal circumstances.15

With large numbers of people on the move, widespread migration has become one of the defining hallmarks of the contemporary period. The previous era, when individuals tended to stay close to home, is over. People’s vision of the world has broadened with the advent of global media such as television and the Internet. Those thinking about going elsewhere can see what the alternatives are and appear to have fewer inhibitions about resettling, especially when conditions in their home country are not very favorable for economic or political reasons.

Immigration is a serious political issue in many countries besides the United States. Comparisons of attitudes toward immigration in western nations shows the United States to be about at the midpoint in the share of residents who think immigration is a problem. According to national surveys, the western country with the highest percentage of citizens who feel immigration is a problem is the United Kingdom (62 percent), followed by 50 percent in the United States, 49 percent in Germany, 47 percent in Italy, 41 percent in Poland, 38 percent in the Netherlands, and 35 percent in France.16 The variation in public attitudes across these nations suggests that citizen anxiety can be managed even when foreigners look and act differently from native-borns. What is needed are national policies that understand the source of public discontent and take actions to minimize public perceptions of immigrant social and economic costs.

IMMIGRATION PATHWAYS

Immigrants come to the United States in three general ways. First, they can become legal permanent residents through marriage, extended family ties, or special skills, or as political refugees. Using visas known as green cards, legal permanent residents are able to live and work in the country. Of the 35 million American immigrants in the United States, an estimated two-thirds (around 23 million) are legal permanent residents.17 Individuals with green cards can apply for U.S. citizenship after five years and become naturalized citizens with full rights such as voting and eligibility for social service benefits.

The second route is through temporary work or tourism visas or through short-term visas for student or government exchanges. These are individuals who come to America for limited periods of time to visit, work, attend government or academic events, or enroll in educational institutions. Among the nation’s immigrants, only about 3 percent (or 1 million people) enter the United States through one of these avenues. Of them, 65,000 arrive through the H-1B visa program for high-skilled workers and 66,000 come through the H-2A or H-2B program for seasonal workers in agriculture, construction, or tourism.18 They are allowed to work in America for three years.

The high-skilled visa program was expanded to 115,000 in 1999 and to 195,000 in 2001 but dropped back to 65,000 in 2004 when Congress did not renew the temporary increases. Critics complained that this entry program disadvantaged American workers and kept wages down for American scientists.19 In 2009, when the country was enduring a deep recession, Congress voted to restrict financial firms’ use of the H-1B visa program. Those financial firms that receiving federal bailout money had to try to hire American workers and then document there were no qualified American applicants before employing foreign-borns.20 The Obama administration has pledged tighter oversight of this program to make sure native-born workers receive fair consideration from companies hiring new, high-skilled employees.21

The third and most controversial mechanism is illegal immigration. It is estimated that one-third of all immigrants (or 11.9 million individuals) are in the United States illegally, many from Mexico. These overall numbers are up from 5 million in 1996 and 8.4 million in 2000. The U.S. Border Patrol reports that 97 percent of illegal border crossers enter the United States through Mexico.22 According to statistics compiled by the Border Patrol, the number of individuals arrested for attempting to sneak over the Mexican line has fluctuated over the past thirty years. The number arrested was 1.7 million in the mid-1980s, 1 million in the late 1980s, 1.6 million in 2000, and 705,000 in 2008. The latter was the lowest number of border-crossing arrests since 675,000 were stopped in 1976. Beefed-up security and a bad economy apparently discouraged some in-migration. Since 2006, 6,000 border patrol agents have been added along the Mexican boundary and 526 miles of fence have been built to enhance enforcement.23

Historically, legal and illegal immigrants have clustered in border states, river ports, or coastal communities, places that were accessible to new arrivals. The East and West Coasts, along with areas bordering Mexico, attracted the most imm...