![]()

PART ONE

INTRODUCTION

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

THE GROWING ASIAN MIDDLE EAST PRESENCE

ASIAN COUNTRIES HAVE TRADED with their western neighbors for centuries. Today, however, as a result of the emergence of China and India as world economic powers and the growth of other Asian economies, the ties between Asia and the Middle East have increased to an unprecedented extent.1 The signs can be seen everywhere. All around the Arabian Gulf, hotels, banks, schools, and shopping centers are managed by Asian expatriate workers, who also provide most of the region's manual labor. Without Asian labor, the oil-rich economies of the Gulf would collapse. Many of the vast construction projects in Doha, Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and other city-states are supervised by South Korean companies. Most of the automobiles and trucks on the street are Japanese or Korean. The endless procession of tankers that sail from the huge ports of the Gulf carrying oil and liquefied natural gas is destined increasingly for the Asian market. Infrastructure projects, including new roads, railways, seaports, airports, gas and oil pipelines, and undersea communication lines, are expanding in both the Middle East and Central Asia, making access between the two regions easier and cheaper.

These trends suggest that, absent a protracted global recession, the Asian presence in the Middle East will continue to grow significantly over the coming decade. However, the strategic implications are far less clear. To what extent will major Asian countries such as China and India be drawn into the complicated, volatile geopolitics of the Middle East? What roles will they take on? How will intra-Asian rivalries play out? And how will Asia's new powers interact with the countries that traditionally have dominated the region—notably the United States? With the exception of Indian and Chinese purchases of military technology from Israel, and Asian arms sales to the countries of the Gulf, the big issues of war, peace, and security in the Middle East have largely remained outside Asia's domain. Will that always be the case? Those are the questions that drive this book.

THE KEY ASIAN PLAYERS

Asia's involvement in the Middle East affects a huge swath of countries, including Pakistan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Australia, New Zealand, and, more indirectly, the countries of Central Asia. All are influenced in some way by the scramble for Middle East energy, the huge amount of money that Middle East oil and gas producers have received and invested, and efforts to seek alternative energy supplies and supply routes. However, four countries merit particular attention owing to their economic and potential military prominence: India, China, Japan, and South Korea.

Over the next thirty years, the economies of India and China are expected to surpass that of the United States in size (although as a result of population growth, their per capita GDP will remain relatively low), giving their governments increased regional and global clout.2 As India and China grow, Japan will be left behind. Nonetheless, Japan is likely to remain a key Asian power, given its close ties to the United States and its growing assertiveness in its relationship with China. Moreover, Japan's energy needs will keep it tied to the Gulf. Similarly, South Korea, while even smaller than Japan, is already deeply engaged in the Middle East, especially in the energy sphere. Lacking domestic oil reserves, South Korea is the world's fifth-largest importer of oil and the eleventh-largest importer of liquefied natural gas.3 In addition, South Korean construction companies have been hired to build oil refineries, petrochemical plants, offices, and infrastructure across the Middle East. Although South Korea's relations with the region have focused on energy imports and construction, efforts have been made to pursue cooperative relations in other sectors as well.

INDIA

The Indian subcontinent has had close commercial ties with the Gulf for centuries, and India today has managed to cultivate good working relationships with all the countries in the Middle East, including Israel. While economic interests have provided the basis for many of those relationships, India has also taken on a modest military role. The Indian government has participated in Middle East peacekeeping operations since 1956, when it contributed troops to the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF), which was established following the Suez crisis. Currently 672 Indian solders make up part of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), and India has provided two of UNIFIL's last four commanding officers, although the government has stated it does not want to become involved in military operations.4 In addition, India has been increasing its bilateral military ties with all of the small countries in the Gulf.

To date, India has not been able to demonstrate significant power or influence in the region. It was humiliated in 1990-91, when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait and hundreds of thousands of Indian workers were stranded in the country. When the workers were released, the Indian government had no way to get them out and had to lease transport aircraft from Europe to mount an evacuation. Because of such frustrations as well as its proximity, India is likely to establish a stronger, more assertive presence in the Gulf over the coming decades.

CHINA

For a short period in the fifteenth century, China was the dominant power in the Indian Ocean, but over the centuries that followed, it had little to do with the Middle East. After the Communist Revolution in 1949, China tried to cultivate close relationships with revolutionary groups in the Arab world, but its efforts were violently opposed by Arab nationalists. In the wake of the Sino-Soviet split and China's eventual rapprochement with the United States in 1972, China changed course and sought instead to establish cordial relations with Middle Eastern governments. In particular, it became more directly involved in the geopolitics of the region through arms sales, notably to Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Iraq, during the 1980s.

More recently, China has followed India's example by becoming engaged in Mideast peacekeeping. China's participation in UNIFIL began officially on April 9, 2006. In addition to three observers, the first forces stationed included a 182-member engineering battalion, including minesweeping, engineering and logistics companies, and a field hospital. The first Chinese casualty occurred on the night of July 25, 2006, when Lieutenant Colonel Du Zhaoyu was among four UN peacekeepers killed by an Israeli air strike that hit a clearly marked UN outpost in southern Lebanon.5 Two months later, the Chinese government decided to increase its troop numbers in UNIFIL to 1,000; in addition, China stated that it would provide Lebanon with roughly $5 million in aid.6

Considerable uncertainty remains regarding China's future presence in the region, particularly in the military arena. China is a long way from the Gulf. If its maritime reach expands into the Indian Ocean and its overland reach grows through Central Asia and Pakistan, it, too, could become a major strategic player in the Middle East. But those are significant “ifs.”

DIMENSIONS OF ASIA'S MIDDLE EASTERN FOOTPRINT

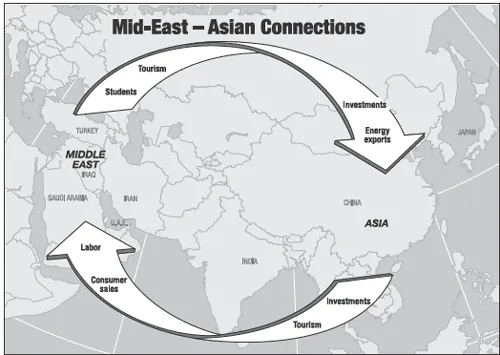

The scale of the Asian powers' involvement in the Middle East can be measured in multiple ways, including by the amount of energy flowing east to Asian markets, the value of Asian exports to the Middle East, financial investment by Asian firms in the Middle East and by Middle Eastern firms in Asia, the number of tourists traveling in both directions, and the number of Middle Easterners enrolling for higher education in key Asian countries (see map 1-1).

ENERGY

Any review of the Middle East-Asia connection must begin with the issue of energy. Asia's need for fossil fuels is the determining factor in its growing interaction with the region, especially with the Gulf. Vast amounts of money are being exchanged as Asian energy consumption and energy imports grow and income from Middle Eastern oil is invested in infrastructure projects both in and outside the region.

Oil. The Middle East and the Caspian basin contain approximately 850 billion barrels of oil—65 percent of the world's estimated 1,300 billion barrels of proven oil reserves.7 At approximately 30 million barrels a day, the region accounts for 33 percent of worldwide oil production. Within the Middle East, oil production is concentrated largely in Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Iraq, which accounted for just over 20 percent of world production in 2005. In 2008, the three countries produced 10.8, 4.1, and 2.4 million barrels a day, respectively. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) and the International Energy Agency (IEA) predict that by 2030, those countries could be producing 12.8, 4.7, and 5.6 million barrels a day, respectively, for a total of 23 percent of world production. By then, the Middle East as a whole is expected to account for 39 percent of world oil production. While the 6 percentage point increase in its share may appear modest, it means that the region will account for more than half of all new production from the present to 2030, when it is projected to produce 18.7 million additional barrels a day, or 56 percent of the total global increase of 33.4 million barrels a day.8

MAP 1-1

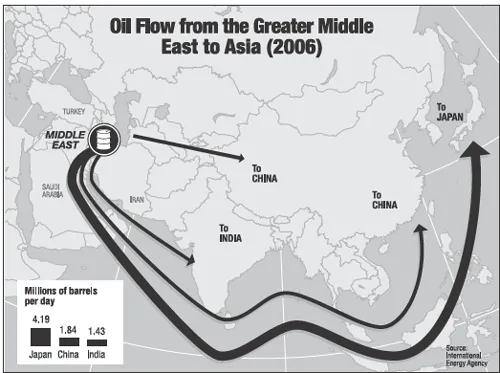

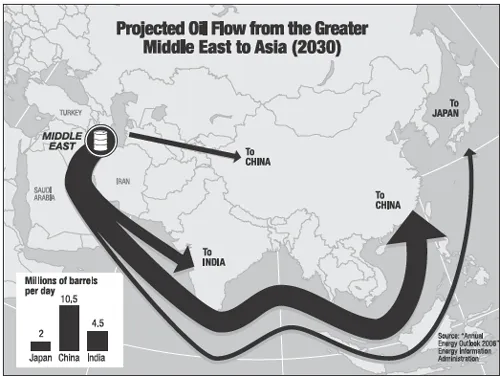

Japan, India, and especially China will consume much of that increase. The Asian market already consumes 23 million barrels a day, representing 30 percent of world demand, and two-thirds of Asia's oil imports come from the Middle East (see map 1-2). In 2006, Japan was the largest Asian consumer of Mideast oil, importing 4.19 million barrels a day, followed by China (1.84 million) and India (1.43 million). However, in the next 25 years China and India are likely to overtake Japan to become Asia's top oil consumers. As map 1-3 indicates, by 2030 oil flows to China will increase to 10.5 million barrels a day and those to India will increase to 4.5 million. Japan's Mideast oil flows will drop by 50 percent, to 2 million barrels a day. Furthermore, by 2030 the method of delivery will have shifted slightly. As oil pipelines throughout Central Asia begin to operate at full capacity, China will switch increasingly to land-based delivery.

MAP 1-2

Source: International Energy Agency.

Of course, such long-term predictions rest on a multitude of assumptions. Iraq is expected to have increased production from 2.1 million barrels a day (in 2007) to 5 million barrels a day by 2030. However, the country's future remains uncertain. Similar concerns could be raised about Iran, where continuing disputes with the United States over Iran's nuclear program and tough international sanctions have prevented Iran from securing the infrastructure funding that it requires to increase production. China and India also are expected to increase their production of oil significantly, but they will not produce anywhere near enough to meet their growing demand for fuel. China produced 3.9 million barrels a day in 2007 and is expected to produce 4.1 million barrels a day by 2030. India produced 900,000 barrels a day in 2007 and is expected to produce 1.3 million barrels a day by 2030.

Natural Gas. The Middle East and Caspian basin also contain 45 percent of the world's proven reserves of natural gas, with approximately 6,200 trillion cubic feet; yet in 2007 the region accounted for only 20 percent of worldwide natural gas production. Although Iran possesses the world's second-largest supply of natural gas reserves and 15 percent of the world's total proven reserves, with 27 trillion cubic meters, it currently supplies only 6.2 billion cubic meters annually, ranking only 25th worldwide. It is an understatement to say that capacity for growth exists in this sector.

MAP 1-3

Source: Annual Energy Outlook 2006, Energy Information Administration.

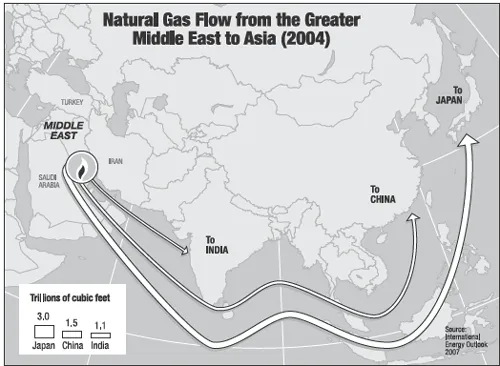

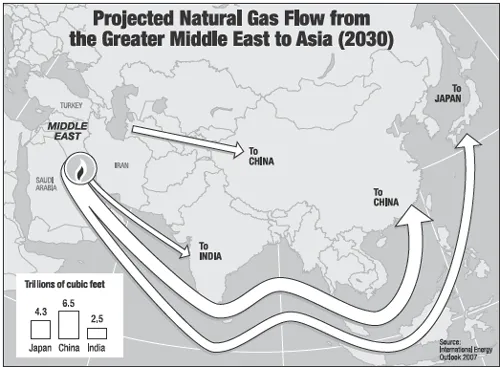

According to the International Energy Agency, the Middle East exported 1.6 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in 2004. Of that, 78 percent went to East Asia, 20 percent to Europe, and 2 percent to North America. Map 1-4 shows the amount of natural gas received by China, India, and Japan. The IEA predicts that in 2030 the Middle East will export roughly 8.2 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, of which 43 percent will go to Asia, 41 percent to Europe, and 15 percent to North America.9 As with oil flows, by 2030 China will overtake Japan as the top importer of natural gas from the Middle East and Caspian basin. However, as shown in map 1-5, all three Asian giants will demand increased quantities of natural gas by that time.

MAP 1-4

Source: International Energy Outlook 2007, Energy Information Administration.

Underlying Assumptions. The preceding projections assume strong economic growth in Asia in the coming decades. As their vast populations ascend into the middle class, China and India are best poised to realize those projections, providing huge post-recession growth to the global economy. However, growth is also likely in Korea and Japan and in the developing economies of Southeast Asia, including Malaysia and Indonesia, which are still recovering from the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s. If the fallout from the 2008 financial crisis is contained and the growth of these economies continues, demand for energy in South and East Asia will rapidly exceed the region's energy production capacity.

In the coming decade, the main Asian oil importers will likely diversify their energy sources in an attempt to reduce their dependence on Middle Eastern oil and natural gas. Wealthier countries, including China, Japan, India, and Korea, will invest in research and development of alternative sources of energy. It is unlikely, however, that the region will be able to substantially reduce its dependence on imports. Instead, the rising economies of Asia will increasingly look outward for new supplies of energy—a dynamic already well documented in the rush to engage Africa seen in China, India, and Japan. Yet no other region can match the capacity of the Middle East and the Caspian basin.

MAP 1-5

Source: International Energy Outlook 2007, Energy Information Administration.

OTHER DRIVERS OF THE ASIAN PRESENCE

While the need for energy may be the major reason for Asia's interest in the M...