![]()

1

Letting Girls Learn

I come to school to learn, so that my life gets better!

—Laxmi, a Prerna alumna

Laxmi, a young Dalit woman, was born in Lucknow in 1992.1 She lives, along with her father and four younger siblings, in a one-room house, a half-constructed, abandoned dwelling they moved into 15 years ago, when her mother was still alive.2

Laxmi is the third child in her family, although the first to survive. Her eldest brother, at 15 months, drowned in a pond at the construction site where her mother was working. A sister died at birth. Though Laxmi’s father is a commercial painter, for several years he has worked only intermittently. Her late mother had been a construction worker, carrying bricks up steep scaffoldings on her head as part of her work. She was married at age 12 and gave birth to seven children in 23 years, dying at the age of 35 in 2005. Laxmi’s father was 14 when he was married and did not attend school after fifth grade because he was required to graze his family’s goats. Laxmi is now the eldest of five siblings, with one younger brother and three younger sisters. She was enrolled in a local school, which she attended irregularly, and dropped out after two to three years because her mother was sick and needed care, as did a baby sister, and because they were poor and had no money to pay her fees.

My sister, Lalita, was born and then my mother had TB. She used to cough a lot in the night, and there was no one to take care of her. I would wake up at night, massage her, put oil on her body; still she didn’t recover. She was sick for months. I had to take care of her, and Radha was very small, so I stayed at home.

Laxmi

Laxmi had been working as a domestic helper since the age of seven, earning 1000 rupees per month (about $15), which went toward food for the family when her mother was not working. Laxmi’s mother had a “uterus surgery” (likely, a hysterectomy) after her seventh child, but was compelled to go back to work at the construction site only three weeks later. The stitches ruptured, and 13-year-old Laxmi took her to the hospital, making several trips back and forth for the next few months.

I used to stay and take care of her, clean her. She vomited a lot and her back used to hurt unbearably. The doctor scolded me for not getting her treatment in time. Father wasn’t bothered. He was drunk most of the time. Then we brought her home, but she started to get worse. Her breathing became very difficult. I got very scared and called all the neighbors. Mother’s sister came and gave some leaves, saying she might get better. But nothing like that happened; she was taking her last breaths. I didn’t know what to do, but I got an auto rickshaw and put her in it. I wanted to take her back to the hospital. But she died right there in my arms in the auto. I couldn’t do anything. Then we were alone. There was no one who could take care of us. So I started working in more homes [seven in all]. Neighbors helped with food and milk for the baby. Lalita [eight-year-old sister] also started working in three homes. Father did nothing. In fact, he sold off the gas cylinder and everything we had for his drinks. He drank all the time and couldn’t take care of us.

One year before her mother’s death, Laxmi found out about Prerna from a friend who was enrolled there.

It had just opened, just one month before I heard about it. My friend told me about it. She told me that the fee is only 10 rupees per month and it is in the afternoon. So I thought, I can pay the fee and if it is in the afternoon, then I can finish my work in the morning, and go to study in the afternoon. It would get over by 5:30, so then I could go back to work in the evening again. So it was perfect. So I joined the school and then my education started again.

She described her day:

In the morning, I made breakfast at home and then left for work at 6. I would go at 6 and come back around noon. Then after bathing, would come to school at 1 o’clock. Then I would study and after that would go to work again from there at 6. It would be 9 to 9:30 by the time I would finish work there. And then I would cook. It would be 11 by the time I would sleep.

She and her younger sister Lalita, nine years old at the time, both enrolled in Prerna, while Radha, the five-year-old, cooked the afternoon meal and took care of the baby at home.

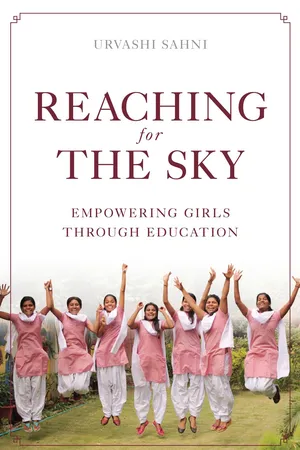

Laxmi is an alumna of Prerna, a school I founded in 2003 for girls with lives like hers, prompted by the belief that all girls should be given access to education. Today, Laxmi has finished her bachelor’s degree.3 She is working at a call center providing services to banks, where she has been recently promoted to head sales manager. She is currently earning 25,000 rupees ($374) per month. Her employers have also offered to pay for her MBA, and she has enrolled. Her three sisters are enrolled in Prerna. Through all these years, she has never given up on her father, despite his neglect and abuse. With her encouragement, he has had some success in overcoming his drinking habit.

Laxmi feels strong. She says:

My life is different from my mother’s. I have controlled my life a lot, taken care of myself, wasn’t married off. Now I might even go to Chennai for a job.

She attributes this change in her life to her education at Prerna, which she says enabled her “to make my life better.” This book tells the story of Prerna, describing how it provided a safe and supportive environment so girls like Laxmi could stay, learn, grow, and become empowered to make their lives better.

Being a Girl

Laxmi’s story, and those of her friends, presents a stark yet vivid picture of what it means to be poor and a girl in India. It also lends a face, flesh and blood, to the statistics about the condition of the lives of millions of girls globally, and particularly in India. According to a survey conducted in 2007, when Indian girls from all castes and social classes were asked if they liked being girls, 48.4 percent said they didn’t want to be girls.4 As we look at Laxmi and her mother’s lives, it is not difficult to see why. India’s daughters, like millions of girls around the world, rich or poor, Dalit or Savarna, are unwanted, unequal, and unsafe at home and on the street.5 According to some estimates, approximately 25 million girls worldwide and one million girls in India are killed before birth as a result of sex selective abortions.6 Furthermore in India girls between one and five years of age are more likely to die than boys the same age because of poor nutrition, female infanticide, and sheer neglect.7 Plan International’s urban program found that, in Delhi, 96 percent of adolescent girls do not feel safe in the city.8 Crime reports say that, nationally, 848 women are sexually harassed, raped, or killed every day.9

Laxmi and her mother’s story corroborate the shameful statistics reported in every account on the status of girls and women around the world. Unvalued, uncared for, victims of neglect and violence, girls and their mothers have lives that are precarious, circumscribed, unfree, and hard. Fathers and husbands exercise enormous, almost absolute, control over the minds and bodies of these girls and women. Laxmi’s mother had no control over the number of children she produced. Despite the fact that her husband defaulted on his responsibility as provider for the family, his traditional role in a patriarchal family which meant she and seven-year-old Laxmi had to take on that responsibility, she continued to suffer his abusive, drunken behavior. According to her world view, she belonged to her husband and he had every right to do what he wished with her. This is a story many of our students tell of their families and homes.

Whereas the intention is not to demonize male figures, fathers, and husbands in Indian society, I do not attempt to hide the truth as told by the girls. The statistics relating to gender-based violence—both domestic and street violence in India—support the girls’ testimony. This book takes a clear look at gender relations and reveals the shameful legacies of patriarchy.

Barriers to Education

Girls in India and everywhere, especially when they are poor, face several societal and school-specific barriers to education just because they are girls.

Child Marriage, Girl Slavery

Early marriage contributes significantly to the curtailment of Indian girls’ lives. Laxmi’s mother was married at 12; her friend Preeti’s mother was married at 13, Sunita’s mother at 13, and Kunti’s at 15. Laxmi’s father and family were ready to marry her off at 14, when she was in grade 8.

He had started from grade 8 only, forcing me because I was growing up, so people who live around [were pressuring him]. Basically it’s society only which forces us to get married [by commenting that] the girl is getting mature, she should be married, she might go wrong. So he would listen to others and tell me to stop studying and get married. That’s what people would say at home; don’t study and get married.

Of the 15 million child brides in the world, more than one-third are in India.10 Child marriage rates in India are the second highest in the world, with Bangladesh topping the list. Of Indian women aged 20 to 24, 47.5 percent were married by age 18, and of these 16 percent start bearing children soon after marriage.11 Given that child marriages are arranged by parents without the consent of the children—in effect, girls are given into physical, economic, psychological, and sexual bondage—it would be more appropriate to describe child brides as girl slaves and child marriage as girl slavery rather than dignifying their status with the term brides. Statistics report that child brides (that is, girl slaves) are more likely to be abused sexually and physically than unmarried girls. For most girls the world over, child marriage means the end of education and the beginning of childbearing. “There is no more abrupt end to childhood than marriage or becoming a mother.”12

Poverty and Gender

Laxmi’s story illustrates how education for daughters is low on the value scale for poor families. Her mother, like 60 percent of the mothers in our school, was illiterate. As with Laxmi, many of the girls enrolled in primary schools are pulled out as soon as a need arises, for all the reasons that research tells us girls in poverty are pulled out: family health issues, burden of domestic work, sibling care, and working outside the home...