![]()

PART ONE

Spiritual Capital: Devotional Networks and a Religious Renaissance

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

City of Women, City of God

Poor, Single, and Holy in Santiago de Guatemala

On May 17, 1713, at age seventy-five, Anna Guerra de Jesús died in Santiago de Guatemala, the colonial capital of Central America. The Dominican and Jesuit orders sponsored sumptuous funerals attended by priests, friars, and government officials. Jesuits carried Anna’s coffin and buried her in the principal altar of their church, the location typically reserved for the Jesuit fathers themselves. Her epitaph read, “she died with the recognition and the fame of holiness.”1 Within three years of Anna’s death, Santiago’s local printing press published a lengthy biography of Anna’s life, penned by her former confessor, Jesuit Padre Antonio Siria and titled Vida admirable y prodigiosas virtudes de la v. sierva de Dios D. Anna Guerra de Jesús (Admirable Life and Extraordinary Virtues of the Servant of God, D. Anna Guerra de Jesús).2

Residents of colonial Spanish American cities delighted in the discovery of holy women close to home. Their lives, full of angst and despair, visions and mystical raptures, inspired devotion and regularly became the subject of evocative biographies and sermons.3 So it is no surprise to find that Santiago de Guatemala celebrated Anna as a local holy woman and published her hagiography (autobiography or biography of a saint or holy person).4 Asunción Lavrín and Josefina Muriel found for colonial Mexico alone approximately 121 books about holy women, most of them cloistered nuns.5

But Anna stands out as an unusual hagiographical subject. While the early modern Catholic ideal of feminine piety prized enclosure, obedience, and virginity, Anna was neither nun nor virgin, but rather a poor abandoned wife and mother. The sixteenth-century Council of Trent and subsequent decrees clearly required cloistered communities for all religious women, including beatas (pious laywomen who took simple vows and lived independently or in communities) and tertiaries (lay women affiliated with religious orders as members of Third Orders). But Anna lived and died in the world as a religious laywoman and Jesuit tertiary. Inquisition records highlight how unmarried and religious laywomen who remained in the world faced marginalization and persecution as the early modern Church more aggressively attempted to enforce Catholic orthodoxy and control female religiosity and sexuality. Indeed, in colonial Mexico, this anxious convergence led the Inquisition to target poor single women, more than any other group, for prosecution as false mystics.6

Anna clearly fits the Mexican Inquisition’s social profile for false mystics. But her spiritual biography illuminates another side to this story, particularly how some women successfully navigated gendered tensions associated with their status as non-elite women living outside both marriage and convent. This chapter explores Anna’s lived religious experience as a poor migrant and abandoned wife and mother, her engagement with female mystical traditions and devotional networks, and her cultivation of alliances with powerful priests and religious orders. It also places Anna’s story within the context of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Santiago de Guatemala, particularly urban demographic shifts and social tensions, as well as movements for spiritual renewal and enthusiastic lay female piety.

Like all hagiographies, Anna’s Vida is an imperfect historical source. Anna’s last confessor, Jesuit Padre Antonio Siria, wrote the spiritual biography based on his knowledge of Anna’s life through their confessional relationship and through spiritual diaries that Anna kept after learning how to write. Unfortunately, Anna’s spiritual diaries went missing at some point in the last fifty years and only excerpts published in the appendix of a modern biography remain.7 Surviving excerpts nevertheless illustrate how Padre Siria, like all hagiographers, filtered Anna’s life story in order to support her cause for beatification, reveal religious truths, and portray his subject above time and space.8 And yet, as Jodi Bilinkoff notes, “if pious biographies are not transparent descriptions of reality, then neither are they so opaque that a close reading goes unrewarded.”9 The historian’s task is to reconnect sacred subjects to their specific contexts, in their historical moment and location.10 This is challenging, but not impossible. Particularly by the eighteenth century, when Padre Siria penned Anna’s biography, hagiographies generally tethered sacred stories to specific historical contexts in an attempt to offer verifiable proof of sanctity for the increasingly rationalistic process of canonization investigations.11 Considering Anna’s spiritual biography within the context of rural El Salvador and urban Santiago de Guatemala around the turn of the eighteenth century sheds light on the relationship between daily life and religious experience and the ways in which laywomen shaped Guatemala’s urban religion.

IMPROBABLE HOLINESS: MARRIAGE AND MOTHERHOOD IN RURAL EL SALVADOR

Santiago de Guatemala claimed Anna as a local holy woman; however, she was not originally from the capital. Born in 1639 in the small town of San Vicente in modern-day El Salvador to a Spanish father and criolla (Spanish American) mother, Anna grew up in a rural environment of small-scale ranching and subsistence farming.12 At age sixteen, Anna married Diego Hernández Vicente and moved to a remote ranch, hours from the nearest town, where she bore seven children, although only two survived early childhood.13

Anna’s life story to this point generally defied the normative gendered model for holy women in the early modern period. Her biographer pointed to early signs of virtue, but absent from the narrative are the familiar early conversion experience, the explicit emulation of female saints, and the heroic rejection of sex and marriage.14 More surprising still, Padre Siria acknowledged that Anna avoided the annual obligation to confess for years, a flagrant violation of Church law punishable by excommunication. He blamed the “shortage of priests and lack of spiritual sustenance” in rural El Salvador, but even after moving to Santiago, Anna passed three years without confessing.15 Far from holy, Anna spent years living in sin in the eyes of the Church. Her biography thus set up the kind of “dramatic turnaround from sinner to saved” more typical in the lives of male saints.16 To explain this unusual transgression in a holy female life, Padre Siria employed a rhetorical trope common in female spiritual biographies—that the devil was tormenting Anna, and the particular form of torment was to deceive her into believing that her sins were too great to reveal in confession.17

Because Anna’s early life lacked traditional markers of holiness and even the most basic obligatory participation in Church sacraments, Padre Siria’s narrative instead emphasized her heroic virtue in the midst of daily suffering—the violent abuse of her husband, her desperate poverty, and the repeated loss of her children. Indeed, Anna’s early visionary experiences revolved entirely around her experiences as a mother and the illness and deaths of her children. Padre Siria recounted that a few days after the death of her first child, Anna had a vision of her son playful and laughing in the arms of the Virgin. And when a much-beloved daughter died, Anna heard celestial music. Padre Siria further imbued the repeated tragedies of daily life with sacred significance and divine purpose, all part of God’s plan to “torment her body and embattle her spirit.”18

Padre Siria may have exaggerated Anna’s suffering for pious effect, but the trials and tribulations he described were more ordinary than extraordinary. Domestic abuse was both legal and pervasive in colonial Latin America, and infant mortality rates were high, especially among both rural and urban poor.19 Similarly, Padre Siria may have exaggerated the poor spiritual guidance offered by rural priests. He repeatedly betrayed an urban bias, contrasting the “barren soil” of Anna’s rural homeland to the “fecund” spiritual environment of Santiago, where the Jesuit order could be a guiding light for her spiritual formation and a “shield for her defense.”20 But rural El Salvador struggled to recruit priests, especially well-trained priests, and had a relatively low ratio of priests to parishioners. Visiting the Salvadoran province in the late colonial period, Archbishop Pedro Cortés y Larraz noted the lack of educated and vigilant priests and bemoaned that even the best priests of the region failed to govern their parishes properly because of the dispersed rural population.21 He dismally concluded that the poor roads and large distances made it simply impossible for many to reach Mass and feast days.22 Peasant women living far from towns, as Anna did, likely had infrequent contact with the sacraments of communion and confession.

ARRIVING TO A CITY OF GOD: SPIRITUAL RENEWAL IN SANTIAGO DE GUATEMALA

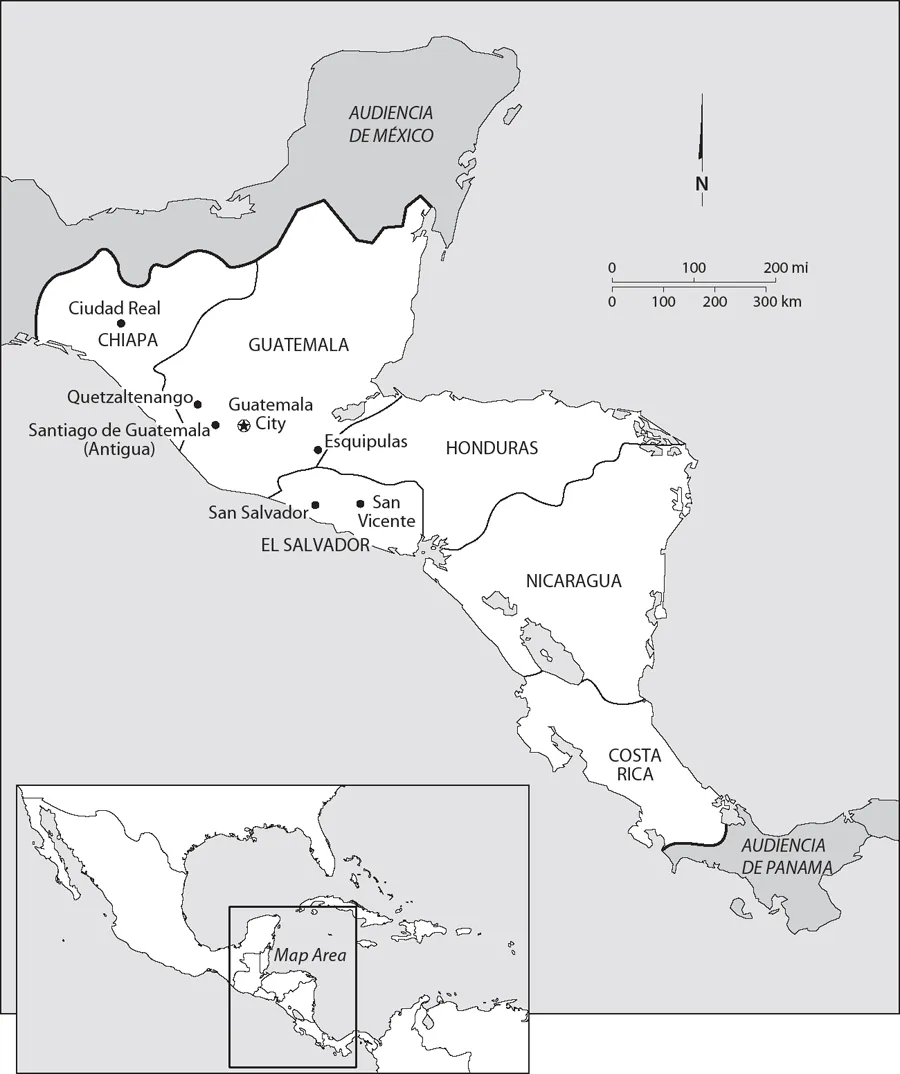

In 1667, Anna and Diego left behind the rural countryside of the Salvadoran province and migrated with their two small children to Santiago de Guatemala.23 Anna lived in Santiago for the next forty-six years until her death in 1713. Beyond the presence of Anna’s sister in the city, Anna and Diego’s exact reasons for migrating are unclear; however, Santiago had long witnessed a continuous flow of migrants in and out of the city. As the seat of the audiencia, or high court, which exercised executive, legislative, and judicial powers, Santiago was the political, economic, and religious capital for the Reino de Guatemala, also known as the audiencia of Guatemala, a region that stretched from modern-day Costa Rica to the Mexican state of Chiapas (see Figure 1.1). Between 1590 and 1650, the capital’s population apparently doubled and by the 1680s Santiago’s population leveled off at close to forty thousand residents, making it at the time one of the largest cities of the Spanish American mainland after Mexico City and Lima.24

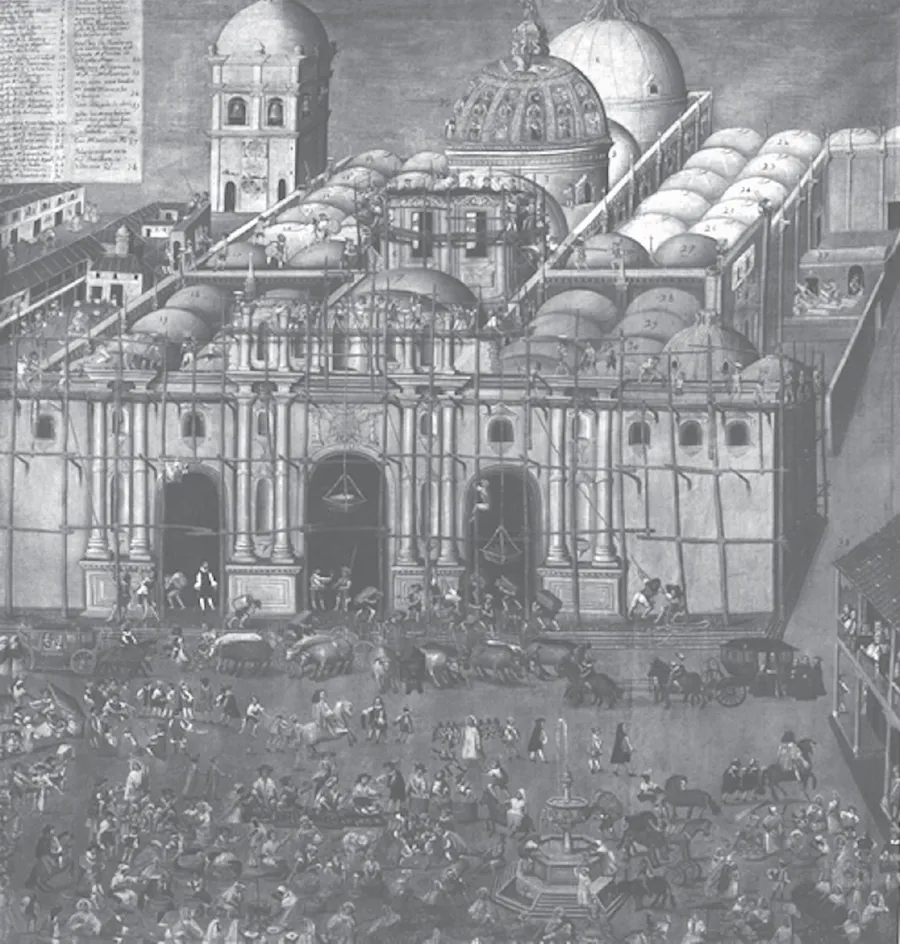

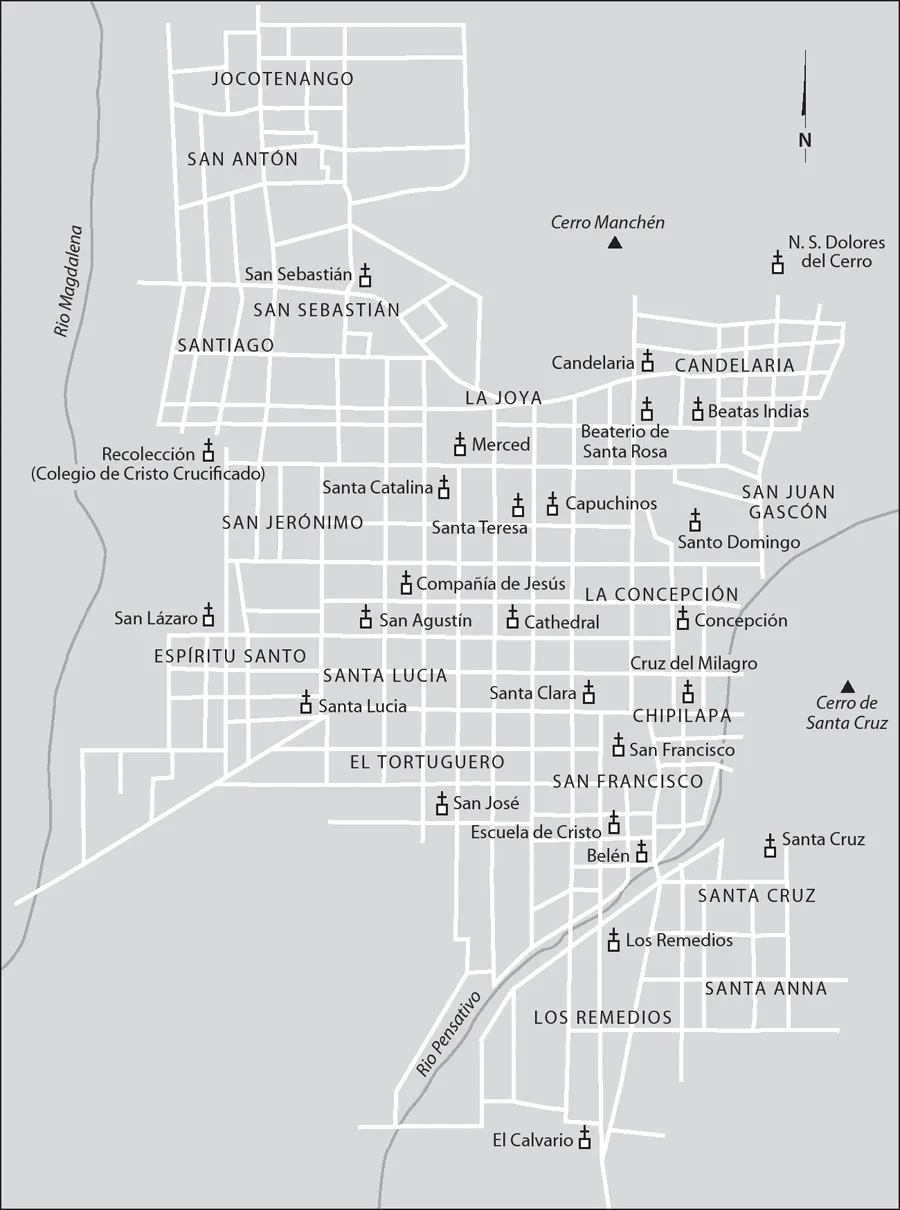

It appears that Anna’s family arrived in the city on the eve of a dramatic shift in the social and cultural rhythm of the colonial capital, which ultimately culminated in the elevation of Santiago to an archbishopric in 1743. A growing urban population and an economic recovery supported new investments in religious and cultural institutions. Just a few years before Anna’s arrival, Santiago initiated its first printing press and around 1680 the city founded the University of San Carlos and built the grand fountain and Plaza of La Alameda—“‘second only to Lima.’”25 But the most magnificent architectural additions to the city were religious foundations. Anna was there to see the opulent reconstructions of the cathedral, as well as the Jesuit and Franciscan churches and the splendid addition of the iconic arched bridge to the Santa Catalina convent (see Figure 1.2 and Figure 1.3). Between 1670 and 1725, the number of female convents in the city also more than doubled, from two to five.26 For rising provincial cities, female convents served as crowning jewels and symbols of pious identity and cultural prestige.27 The only other city in all of Central America that could claim a female convent during the colonial period was Ciudad Real in Chiapas. The turn of the eighteenth century proved to be the pinnacle of monastic institutions in Santiago, with evidence suggesting that more than 10 percent of Spanish women were professed nuns, and hundreds more women were housed in convents as students, servants, and slaves.28 Most of the servile population was indigenous or of African descent.

Figure 1.1. Map of colonial borders of the audiencia or Kingdom of Guatemala. Based on map by Christophe Belaubre.

Figure 1.2. Antonio Ramírez, Cathedral of Santiago de los Caballeros (Guatemala, 1678).

Figure 1.3. Map of Santiago de Guatemala, ca. 1770. Based on map by Christopher Lutz.

Coming from a rural environment where she had infrequent contact with priests, Anna must have been struck by Santiago’s dense and growing concentration of priests and friars. Between 1650 and 1750, the number of priests ministering within Santiago doubled, from five hundred to one thousand.29 By the early eighteenth century, Santiago’s religious orders included close to four hundred friars. Parish priests and friars worked together to foster devotions and reinforce Catholic orthodoxy, but like other Spanish colonial cities, Santiago was also rife with competition and rivalries as religious orders openly vied with each other and with secular parishes for devotional followers.30

The late seventeenth century witnessed a vibrant spiritual renewal within Santiago’s lay community as well, fueled by a fervent urban missionary movement and enthusiastic lay piety. The Holy School of Christ religious brotherhood, founded in Santiago in 1664, brought laymen and priests together in a devotional regime of spiritual exercises, physical penance, frequent engagement with the sacraments, and acts of mercy such as visiting hospitals and prisons.31 In the late seventeenth century, the Holy School of Christ transformed into the religious order of the Congregation of San Felipe Neri, known for its cultivation of missionary zeal, dynamic preachers, and gifted and dedicated confessors.32

Joining their efforts were the apostolic Franciscan friars of the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Propaganda Fide), w...