![]()

Chapter 1

An Atlantic Institution

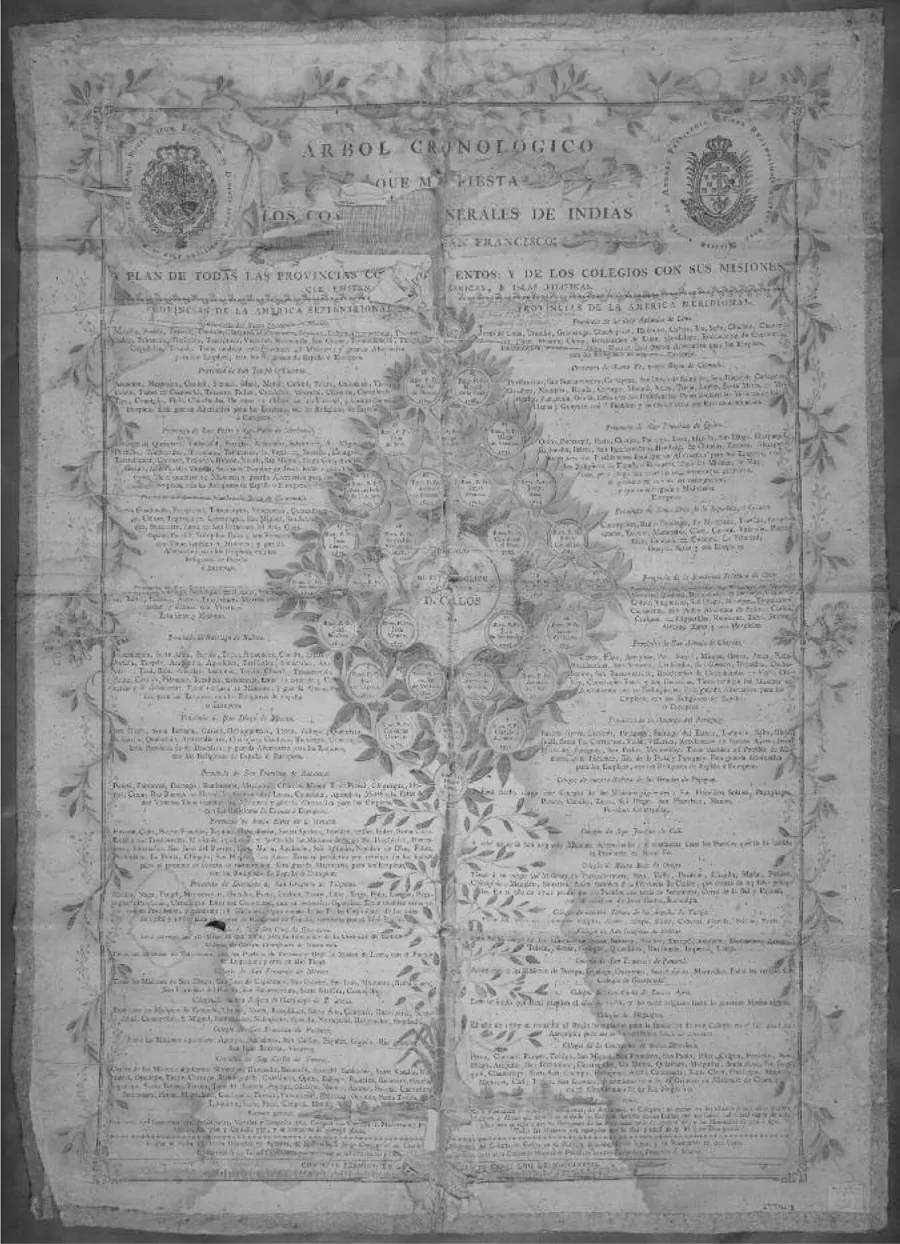

Upon entering the research room in the Franciscan archive at Celaya,1 researchers note a prominently displayed organizational chart of the Franciscan Order in Spanish America dated 1789 and printed in Lima. Fray Pedro González de Agüeros, a missionary from the Colegio Apostólico de Ocopa in Peru, painted a perfectly symmetrical genealogical tree consisting of the Franciscan commissaries general of the Indies. Commissaries are arranged chronologically on branches from the trunk to the peak, where the name Fray Manuel María Truxillo appears, González de Agüeros’s contemporary. This allegorical symbol is a Franciscan adaptation of Jesse’s tree, a type of representation that depicted the royal lineage of Jesus of Nazareth that was very popular in the Middle Ages. In the sixteenth century, religious orders adopted the genealogical tree to describe themselves, typically with their founders as the root that sustained the tree. In the picture on Celaya’s wall, the print is topped by the royal coat of arms and the crest of the commissary general of the Indies on opposite sides. Moreover, the author dedicated the printed leaflet to King Charles IV. González de Agüeros sent an undeniable message of the union of the monarchy and the Franciscan Order in Spanish America. His loyalty to the king is indisputable—all of his opus magna of books and maps centered on Ocopa’s missionary endeavors were dedicated to the monarch.2

González de Agüeros’s print is a eulogy to the Franciscan missionary endeavors in America. The tree divides the composition into two lists of all the Franciscan provinces (provincias), convents, custodies (custodias), propaganda fide colleges, and missions in North and South America, respectively. Each list begins with the first (or “mother”) province established on each continent on top and continues chronologically through provinces established thereafter, and finally the colleges of propaganda fide alongside their missions at the bottom. This printed leaflet is an exaltation of the Franciscan commitment to the evangelization of America, which comprised 17 provinces, 231 convents, 164 vicar houses and hospices, 14 apostolic colleges, 1 custody (in Sonora), and a total of over 300,000 neophytes ministered to by 4,500 to 5,000 provincial friars and 700 to 870 apostolic propaganda fide missionaries. As art historian Jesús Pérez Morera points out, genealogical trees have both an historical and a mystical meaning. This type of allegorical composition coalesces the history of the Franciscan Order in America through the commissaries general of the Indies, its commitment to the expansion of Catholicism in America, and the relevance of the Spanish monarchy. By placing the colleges on both sides of the trunk and the provinces at the level of the branches, González de Agüeros accentuates the colleges evangelical role in converting America to Catholicism. Genealogical trees include the founder of the order at the base of the tree, as the root of the group, while the trunk constitutes the grounding for the order’s expansion.3

This chapter examines the institutional genesis and consolidation of these colleges and their atypical raison d’être in a time when secular forces had halted mendicant expansion in Spain and its empire. According to González de Agüeros, the Franciscan evangelical program owed its existence to both the colegios and provincias. However, in the eighteenth century the colleges became a new missionary vanguard, the trunk of Franciscan evangelism in Spain and Spanish America. Due to their strong commitment to conversion (internal and external) and soteriological responsibility, as well as certain innovations brought to the Franciscans, the Franciscan propaganda fide institution grew rapidly. In a sense, an institutional survey of the colleges serves as the background for the following chapters.

This chapter describes the organizational structure of the colleges to better understand their missionizing agenda. College leaders directed the evangelical program, dealt with government and ecclesiastical bureaucracies, and comprised the first stage of appeals when problems arose. To improved effectiveness and response, American and Spanish colleges remained uniquely independent from the Franciscan provincias and under the authority of Franciscan general commissaries in Mexico City, Lima, and Madrid. Yet the colleges’ uniqueness was in some ways as traditional as innovative. Changes were introduced that revitalized the Franciscan evangelical ministry and thus spoke to the spirit of reform and evangelization present in the order since its beginnings. The colegios de propaganda fide did not, however, remain pristine, monochromatic, inert institutions. This chapter also exposes conflict with provincias and rivalries both internal and external to the propaganda fide communities. Such fissures demonstrate that the Franciscan propaganda fide colleges were far from homogeneous institutions free from tribulation.

Fig. 1.1. Arbol Cronológico que manifiesta los comisarios generales de Indias del Orden de San Francisco y Plan de todas las provincias con sus conventos: ϒ de los colegios con sus misiones, que existen en las dos Américas, é Islas Filipinas (Madrid: Imprenta de Benito Cano, 1789). Courtesy of the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania.

Even with their shortcomings, college administrators responded to difficulties and challenges in various ways. To illustrate this point, I focus on how reforms coming from Madrid in the last decades of the eighteenth century and before the American revolutions affected the colleges’ business of conversion and salvation. At the core were centripetal forces around Madrid’s bureaucracy to control and transform the empire into a reliable long-term resource of expanding wealth and political loyalties. The colleges accommodated, while simultaneously challenging, the new laws that emanated from Madrid. The chapter begins with a description of the context in which the colleges operated as a new vanguard of missionary work, a polished and lubricated mechanism (albeit imperfect) for the “conversion of souls.” In the end, the Franciscan apostolic colleges evolved towards an imperial, centralizing institution that dominated the Spanish missionary scene in the twilight years of the empire. Why and how it happened deserve some reflection.

The Plan to Convert the Spanish Atlantic World

As Fray Pedro González de Agüeros stressed in his genealogical imprint, Franciscan convents multiplied throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to become the largest religious order in terms of manpower and geographical reach by the time the first colegio was established in Querétaro in 1683. In the Americas, the Franciscan evangelical program quickly spread among native communities in the aftermath of conquest through the creation of parishes to evangelize Indians in rural and urban areas, called doctrinas. Succinctly put, networks of Franciscan convents and Indian doctrinas were organized around custodies (custodias) and provinces. The missionary front continued its expansion in North and South America, bringing new lands and peoples under Spanish control. In an iterative process, doctrinas became Indian parishes, for the mendicant orders custodias became provincias, and diocesan parishes were established in Spanish towns.

In North America, the arrival of twelve Franciscans after the fall of México-Tenochtitlán in 1524 set in motion an evangelical program of conversion and acculturation that both made possible as well as sustained Spanish domination. New Spain’s provincial map included the early Provincia del Santo Evangelio (Province of the Holy Gospel), established in 1534, and subsequent provincias of Yucatán (1559), Michoacán (1565), Guatemala (1565), Nicaragua (1675), Discalced San Diego de México (1599), Zacatecas (1603), Xalisco (1606), Florida (1612), and Río Verde (1645). A similar pattern is found in the viceroyalty of Peru, where the Franciscan Provincia de los XII Apóstoles del Perú (1553) split into the provinces of Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, and Chile in 1565, Venezuela in 1585, and Río de la Plata in 1612. Demographic studies and contemporary sources reveal the predominance of the Franciscan Order on the ecclesiastical map of the Spanish Atlantic by 1700.4

A priori, the late seventeenth century did not seem an auspicious time for establishing a new Franciscan missionary venture. Criticism of mendicants in general and especially the Seraphic Order paralleled its expansion. Franciscans confronted several antagonistic groups from within and without. A succinct summary then stresses the significance of establishing the colleges in the late 1600s. By the end of the seventeenth century, the mendicant orders had resisted more than a century of conflict with bishops over control of Indian parishes. Since their early arrival in Mexico, mendicants had enjoyed special papal and royal prerogatives over the administration of Indian doctrinas that included spiritual as well as economic benefits commonly reserved for diocesan clerics. In Europe, bishops supervised the administration of sacraments and collection of tithes, and inspected and exercised control over the parishes. In America, popes and kings had turned these privileges over to the mendicants in reward for their undertaking the evangelization and conversion of native peoples. Consequently, bishops continuously challenged the Franciscan monopoly over these Indian parishes. The secularization of Franciscan doctrinas—the process of turning parishes administered by Franciscan priests over to the diocesan clergy—happened slowly. Overall, Franciscans in particular and mendicants in general withstood the secularizing impetus until the mid-1700s. The continuous assaults had failed due to the mendicants’ ability to defend their privileges as well as the real difficulties faced by diocesan authorities to fill the vacuum once friars left their doctrinas. Finally, in the mid-eighteenth century, a series of royal edicts passed between 1749 and 1753 gave the final blow to the doctrinas when mendicants hesitantly turned over most parishes to the dioceses (bishoprics) in Spanish America.5

Government officials also raised their voices against expansion of the mendicant orders, which some considered the core of problems faced by Spain throughout the seventeenth century. Among the most persuasive foes of religious expansion were economic counselors called arbitristas, who linked Spanish economic and imperial decadence to religious excesses and inability to produce economic (material) progress. Their opposition to additional religious convents had resulted in royal prohibitions of new establishments and the mendicants’ consequent gridlock in eighteenth-century Spain and in Spanish America, excepting at the ever-expanding frontier. Throughout the eighteenth century, enlightened reformers received the baton from the arbitristas to put the mendicants on the defense. Reformers viewed mendicant orders as economic burdens that hoarded resources which otherwise could be used to promote Spain’s incipient industrialization.6

In contrast, the Franciscan Order’s internal critics aimed at reform and enhancement rather than imposing personnel and geographic limitations. Similar to critiques in previous centuries, Franciscans censured decadence in various forms and missionizing shortfalls in America as well as Spain. It should be noted that the demographic peak for Franciscan friars and houses in the Hispanic world coincided with perceptions of spiritual laxity and a loss of momentum in the evangelical ministry vis-à-vis the secular clergy and other regular clerics, particularly the Jesuits.7 Such was the case of Fray Gregorio de Bolívar, a friar stationed in Peru in the early seventeenth century, who has been described by scholars as a precursor to Fray Antonio Llinás’s plan to establish colleges to train Franciscan missionaries in Spain and the Americas. While the link is tenuous at best, Bolívar submitted his reform project to the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Sagrada Congregación de Propaganda Fide), an institution founded in 1622 by Pope Gregorius XV with the support of the Franciscan Order to monitor and advance missionary programs in foreign lands. The Congregation welcomed ideas that fostered the expansion of Catholicism as much as offered a platform for critics to meddle in American ecclesiastical affairs. Lured by the opportunity, dissenting voices like Bolívar’s used the Congregation to raise their objections on the state of the Church in the Americas. Disenchanted Franciscan missionaries actively used this new venue to appeal to Rome to repair missionary agendas and Rome welcomed the same as a means to intervene in otherwise out-of-reach Spanish American matters. Bolívar’s report deserves some attention because his concerns and proposals would reverberate with the genesis of the colleges sixty years later.8

In the mid-1620s, Fray Gregorio sent a report to the pope that questioned the Church’s missionary commitment and sought reforms. The friar predictably painted a picture of Church decadence in Peru. According to the report, secular and regular clerics had lost their evangelical zeal and relaxed their customs by allowing and actively participating with natives in gambling, smuggling, and in illicit (for mendicants) buying and selling activities with laypeople (including Indians). He further denounced the clerics for selling alcoholic beverages to the natives, which, he argued, perpetuated idolatry and immoral behavior. Overall, Indian doctrinas under secular and regular clerics had become, he asserted, “seedbeds of incredible evil, because here greed, forbidden and exorbitant gambling, fraud and abuses, and all manner of decadence flourish.” He particularly decried the prevalence of lewdness and immodesty, resulting from these practices.9

Indubitably, according to Bolívar, reform of the clergy’s ruinous state in Peru was much needed. As a solution, he advocated establishment of colleges in each bishopric, “where a certain number of students be trained and educated according to the opportunity and convenience of each bishopric.”10 Under this plan, each religious order should have at least one facility dedicated to the study of languages of nearby native peoples, where a third of the students would be trained and sent to frontier missions. Even though his project was not approved, the friar’s ideas mirror the future Franciscan colleges for the propagation of the faith.

Indeed, Fray Bolívar had many peers with similar objectives. Debates to create colleges to improve potential missionaries’ language and oratory skills had positive results throughout the century and culminated with the creation and expansion of revitalized conversion schemes. Founded under the auspices of the Sagrada Congregación de Propaganda Fide in Rome, also in 1622, the Colegio de San Pietro Montorio sent missionaries to the Far East and Middle East. Students at Montorio attended language classes—Arabic, Chaldean, Ethiopian, Albanian, Greek, and Chinese—while also studying under newly appointed chairs for the study of theological controversies (primarily concerning Protestantism), doctrinal and moral theologies, sacred scriptures, medicine, mathematics, and geography. In 1628, the Spanish pri...