![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Disorders of a New Order

The Levant in the Long Eighteenth Century

It is worth reiterating that it is not so much the literacy of the eighteenth-century barber that is surprising, it is his authority. This chapter investigates the sources of the authority of our nouveau literates. What is it that impelled or gave confidence to a barber, a Greek Orthodox priest, a couple of Shī`ī farmers, a Samaritan scribe, a Ḥimṣi court scribe, and a couple of Damascene soldiers to write? What is it in the social and cultural landscape of the eighteenth-century Levant that prompted these people, whose professions, strictly speaking, fell outside the learned professions and especially history writing, to write chronicles? In short, this chapter is about nouveau literacy as a social phenomenon.

In search of the sources of the nouveau literates’ authority, I focus on Damascus, the city in which the barber was born, and which was undeniably his own. Ibn Budayr’s possession of the city is evident in his marking of the city’s features: its neighborhoods, streets, bazaars, bathhouses, coffeehouses, shops, colleges, and mosques. In his chronicle, a cartography emerges in which the city is not just a list of places but a veritable habitat. It is home to all kinds of people: notables, scholars, merchants, soldiers, mystics, shopkeepers, prostitutes, and possessed individuals. It is a city where natural beauty and divine grace abound, but it is also a place of mysterious murders and curious suicides, of immoral revelry and marital infidelities. It is the hometown of the great Sufi thinker `Abd al-Ghanī al-Nābulusī, the poet laureate Bahlūl, and the impossibly seductive prostitute Salamūn.1 Despite Ibn Budayr’s anger over and frustration with the corruption and disorder in the city, the barber narrates his Damascus lovingly, proudly, and protectively.

Damascus is important not only because it is the barber’s home. It happens to be one of the five most important cities in the Ottoman Empire and a chief provincial capital. It is the center of Ottoman rule in the region, and a recipient of imperial orders, benefits, and personnel. It is the node from which imperial power is distributed and competed for. Thus, Damascus functioned as a microcosm of the empire and often mirrored its capital, Istanbul. In addition to its political significance, Damascus’ cultural and social (hence, economic) wealth was abundant. Historically one of the most important knowledge centers in the Islamic world, in the eighteenth century it became the point of departure of the northern pilgrimage route to Mecca. In these capacities, Damascus was the center of religiously and intellectually motivated traffic. For all of these reasons, the first place to look for the sources of authority in the eighteenth-century Levant, even the authority of “unimportant” nouveau literates, is the Ottoman provincial capital par excellence, Damascus, in which a great deal was happening.

FIGURE 1. A View of Eighteenth-Century Damascus. The image shows the centrality of the Umayyad Mosque. Oil painting by an anonymous artist. Source: Gerard Degeorge, Damascus. Translated from French by David Radzinowics (Paris: Flammarion, 2004).

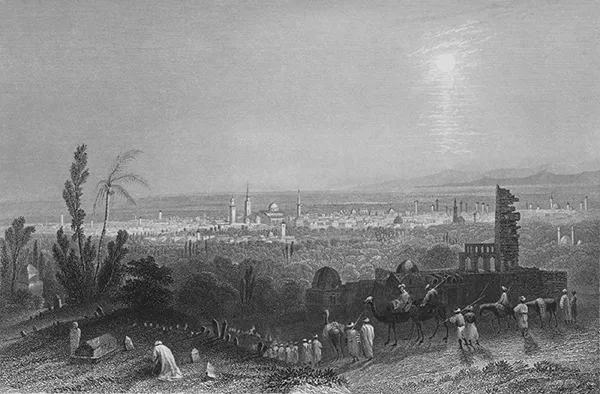

FIGURE 2. Damascus from Above Salahyeh. Source: Syria, the Holy Land, Asia Minor, &c. Illustrated. In a Series of Views Drawn from Nature by W. H. Bartlett, William Purser &c. With Descriptions of the Plates by John Carne (London, Paris, and America: Fisher, Son, & Co., 1836).

The Levantine eighteenth century represented a reconfigured social and political map, a new order of sorts. This order was constituted around the emergence of new households and networks, which afforded fresh opportunities to individuals and groups, and through which many experienced a change in social position or status. I trace the contours of this order by exploring the socioeconomic and political processes that undergirded it, and I locate in this new order a changed urban topography. It is inside the city of Damascus itself that I look for the manifestations of this new social topography not only in an altered cityscape of exhibitionism and violence but also in a more public sociability exemplified in a culture of the outdoors. This (more) public culture is evident in ostentatious buildings, some in imperial style, and in the visibility of new segments of society, such as women and minorities. In the eyes of contemporaries, including our barber, these changes represented not a new order but a condition of outright “disorder.” I argue that the chronicles of the nouveau literates constitute part and parcel of this social and cultural change, as a literary disorder of the new order.

The barber and all the other new historians in our sample benefited from the changes in the region, whether as individuals or as members of a larger community. This enhancement in status afforded these individuals the confidence to celebrate, even flaunt, their rise, and it raised the stakes considerably. In a new position there was much more to lose. Whether to count their blessings, issue rebukes, or complain about the vicissitudes of time, these nouveau literates wrote chronicles to negotiate in a changed world. Having experienced social mobility, and prompted by hope and fear in their new positions, these authors used the publicness of the text to negotiate and exhibit their altered situations. Consequently most of their texts were public displays, inexpensive “monuments” to match the new urban architecture itself.

A RESHUFFLE IN THE SOCIAL TOPOGRAPHY

Despite (or perhaps because of) military defeat and territorial loss, the Ottoman Empire in the long eighteenth century has come to be seen as constituting a new order.2 Politically, the clearest manifestation of this phenomenon is the externalization of the authority of the sultan to households outside his own. The capital city witnessed the rise of “vizier-pasha” households,3 while the provinces saw the rise of powerful local gubernatorial families.4 In the province of Damascus, local rule came tinged with a dynastic flavor. For much of the century, the al-`Aẓm family ruled the province with the exhibitionism, pageantry, and panache of a royal household.5

In many ways, the al-`Aẓm family represented a new creature. And the new creature came with a new fiscal deal: the mālikāne, a system of tax farming, which almost amounted to private land ownership.6 The beneficiaries of this system were the governors and other members of the local elite, whether `ulamā’ or commercial families. Competition over the purchase of rights over these tax farms, auctioned to the highest bidder, was the order of the day. “Wealth pulls along more wealth,” as the Arabic proverb goes7; those who were able to offer advances for a mālikāne found generous reward.8 Thus, in seeking to explain the eighteenth-century phenomenon of the rise of the notables (a`yān), scholars have determined that the new tax-farming system constituted an important economic basis that facilitated the social and political dominance of new figures and households.

Another economic factor that seems to have contributed to the changes in the eighteenth-century political landscape is the intensification of global trade because of European demand for cash crops such as cotton, silk, and grain. The emergence of port towns at the expense of traditional inland commercial centers reflected a shift in trade patterns toward the sea.9 The point here, however, is that integration into the world market brought about what is usually expected of the integration into the world market: new avenues for political and economic power. The ascendancy of the tribal strongman al-Ẓāhir al-`Umar (d. 1775) is a case in point.10 Having monopolized the cotton trade in Palestine, al-`Umar managed to garner the strength—and audacity—to challenge Ottoman rule from his newly fortified costal town of Acre. As we shall see, al-`Umar was ubiquitous in the region and consequently in the chronicles of the time. Often cast as the villain, but sometimes as the good ally—depending on who is reporting—al-`Umar eluded the representatives of Ottoman rule for a long time. Whether the good guy or the bad, al-`Umar rebelled with style,11 which made him the subject of epiclike narrations of the variety we will encounter in Chapter 5.

The Levantine eighteenth century was also about a new sectarian order, which manifested itself in the rise to prominence of the Greek Catholic community. The origin of these dreaded schismatics—as the Greek Orthodox held them to be—dates back to the late seventeenth century, but their dominance in the subsequent century is intimately intertwined with their active role in the reinvigorated Mediterranean trade. Through conversion to Catholicism, this community sought to free themselves from the control of the Orthodox Patriarchate in Constantinople. Significantly, the community rose at the expense of their former co-religionists the Greek Orthodox, but by the end of the eighteenth century they had also superseded the local Jewish community, especially the Fārḥī family, who were hitherto the preferred custom collectors and financiers.12

Thus far, I have described the new order in terms of “rise” and “fall,” which are the current terms in modern scholarship. However, these stories of rise and fall should not be seen as isolated trends in an otherwise unchanged society. Rather, I will argue that the emergence of new figures, families, and groups reflected a larger and deeper social flux, in which both the “middling sort” (say, a barber, a farmer, or a minor soldier) and the culturally nondominant (say, a Greek Orthodox priest or a Samaritan scribe) also experienced or stood to experience change in social position. In order to integrate nonnotables into the picture, one must readjust the view such that the focus is less on the fact and identity of the new elite and more on the mode and place of their operation, that is, on the dynamic of family patronage and its base, the elite household.13

The new order can be viewed as simply one of the appearance and dominance of new families whose households became the nodes and loci of social networks that extended beyond kin. The nature and extent of the power of the household differed according to occupation and social and/or political functions of the family. Whether these were large military-administrative households, smaller wealthy merchants, or distinguished `ulamā’ families, they were generally rich, fiercely competitive, and decidedly local. However, for the perpetuation of their power, these families needed to cultivate connections further afield in the places that mattered most, often the imperial capital itself.

Although the shenanigans that went on between the local notables and their Istanbul patrons are known to the modern histo...