![]()

1 UNSCOM’S INCEPTION AND INFANCY

WITH IRAQI ARMED FORCES at a significant disadvantage,1 the outcome of the 1991 Gulf War was sufficiently foreseeable for some to turn to post-war planning before the onset of hostilities. Before 1990 ended, possible ceasefire conditions and mechanisms were discussed in the capitals of major Coalition partners, particularly with regard to the disposition of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction after the war. As policymakers mulled over whether to demand Iraq’s complete unconditional surrender against less draconian options, the draft of what became United Nations (UN) Security Council Resolution 687 began to circulate in the Security Council’s chambers.2 The resolution stipulated that Iraq agree unconditionally to allow the UN to remove, render harmless, or destroy its weapons of mass destruction and ballistic missiles; established the UN Special Commission (UNSCOM) to effect the majority of that mandate; and directly linked the lifting of trade sanctions to Iraq’s compliance with the disarmament mandate. The Security Council’s approval of Resolution 687 on April 3, 1991, set UNSCOM on a course of forced disarmament of a sovereign nation defeated in war, a feat rarely attempted, much less successfully executed, in modern history.3

This chapter first recounts the circumstances surrounding the creation of UNSCOM. Iraq’s initial null and elliptical declarations about its biological activities are then juxtaposed against the Western intelligence assessment of Iraq’s bioweapons status prior to the 1991 war. The narrative then describes UNSCOM’s early inspections, the strategy and tactics Iraq employed to try to dupe the inspectors, the reasons Saddam Hussein sought to retain a biological weapons capability, and the adjustments the inspectors began to make to contend with Iraq’s uncooperative behavior.

From the outset, UNSCOM and Baghdad took calculated risks. As Iraq chanced that it could swiftly hide incriminating evidence and fool the inspectors, UNSCOM’s meager corps of inspectors set out to disarm it unaware of Saddam’s already activated concealment strategy and the true scope of Iraq’s unconventional weapons programs. Just as UNSCOM’s inspectors did not know how far and hard they could push Iraq to find the truth, Saddam could not predict the skill level and determination of the inspectors or the Security Council’s resolve to enforce the ceasefire conditions. Amidst those early post-war months, the leaders of UNSCOM and Iraq received disquieting glimpses of the challenges ahead but neither knew just how demanding it would be for UNSCOM to certify Iraq’s disarmament to the Security Council or for Iraq to persuade UNSCOM and the Security Council that its unconventional weapons ambitions and capabilities were a thing of the past.

OPTIMISTIC EXPECTATIONS

The U.S. and British governments prepared the first draft of Resolution 687, putting UNSCOM in charge of all disarmament efforts in Iraq.4 Without expert technical advice on what would be needed to find and secure Iraq’s chemical arsenal and ballistic missiles, to determine the extent of its suspected nuclear and biological weapons programs, and to disarm it of these capabilities, Resolution 687’s architects based the disarmament framework largely on what U.S. and British intelligence services knew about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction programs and the idea that a step-by-step process would be needed. The group drafting process took a week or two at the most. “We were really under intense time pressure,” said Robert Gallucci, who later became UNSCOM’s first deputy executive chairman.5 The French argued that the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which judged Iraq’s nuclear pursuits before the 1991 Gulf War to be purely peaceful in nature, had to be in charge of destroying any nuclear weapons capabilities that might be uncovered. The final version of Resolution 687 thus directed the IAEA to carry out these duties with UNSCOM’s cooperation and assistance but gave UNSCOM alone the authority to designate additional sites for inspection that Iraq did not voluntarily identify as being involved with prohibited weapons activities.6

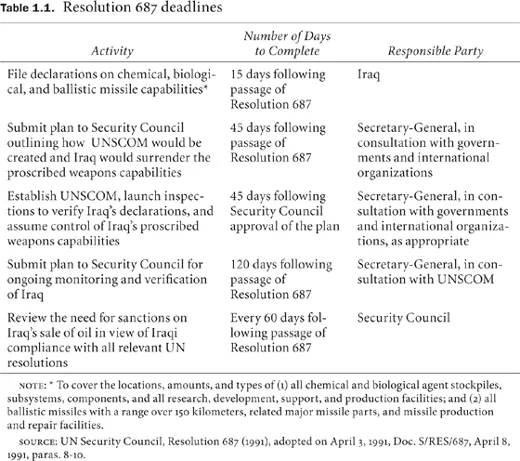

One feature of the ceasefire resolution quick to draw derision was its “laughable” deadlines for reporting and activity, described in Table 1.1. Those with field experience in the safe destruction of weapons found fault even with the fifteen-day deadline for Iraq to submit a declaration, the simplest task to be accomplished. Deadpanned one such expert, “People who didn’t have a great deal of expertise came up with those deadlines.”7 The group that penned Resolution 687 “just made those deadlines up,” conceded Gallucci.8 The resolution’s terms reflected the political pressure to end hostilities, the unusual international political environment just after the Cold War, and the speed of Iraq’s defeat.9 An overall sense of optimism infused multilateral efforts to address global problems in the early 1990s, making for a “gold rush mood . . . that everything would be over in a few months. It wasn’t apparent right away that the inspections would get tough.”10 Recalling this buoyant period, “We took on the Iraqis, they got whipped, everything of interest had been bombed to smithereens, and the Iraqis would want to get out from underneath the sanctions and would cooperate. In that sense, the deadlines weren’t seen as unrealistic.”11

Before long, the U.S. State Department shifted Gallucci to New York to buttress U.S. Ambassador to the UN Thomas Pickering’s drive to win Security Council approval of the resolution and to set up UNSCOM. Joking that he had not been to the UN since a fifth-grade field trip, Gallucci was thrown into meetings with Secretary-General Javier Peres de Cuellar and UN Undersecretary for Disarmament Yasushi Akashi, who advised following UN practice and staffing UNSCOM with diplomats representing an equitable geographic balance from around the world. Knowing that specific technical skill sets would be required to locate and eliminate Iraq’s weapons and that “diplomats from Uruguay don’t do that,” Gallucci felt that he “was awkwardly positioned in these talks.” Worse, he was firmly instructed not only to press for Swedish diplomat Rolf Ekeus as UNSCOM’s executive chairman but to nominate himself as Ekeus’s deputy. This “doubly ugly, perfectly awful” situation mortified Gallucci, who groped for the right words to convey U.S. preferences to the world’s top diplomats.12

On April 3, the clock started ticking on Resolution 687’s deadlines.13 Ambassador Ekeus remembered being approached the very next day about the UNSCOM job. Regarding the text of Resolution 687, Ekeus was struck by how unmistakably paragraph 22 tied Iraq’s disarmament to the lifting of trade sanctions. Ekeus believed that Baghdad had a strong motivation to cooperate fully with UNSCOM since oil sales were Iraq’s primary source of income. Moreover, he anticipated sharp criticism from Iraq if he did not proceed summarily. As he swung into action to launch UNSCOM, the humanitarian costs of extended sanctions weighed heavily on him: “I felt I had to rush, that I couldn’t even allow more than one day than is absolutely necessary before completing my task.”14 Convinced that Iraq could be swiftly disarmed, Ekeus accepted the UNSCOM chairmanship on the condition that the Swedish government did not replace him as ambassador to the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, allowing him to return to Geneva within a year or so.15 As with Ekeus, prevailing opinion among policymakers and UNSCOM insiders held that UNSCOM would only be in existence for a year or two at the most.16

Landing in New York, Ekeus provided UNSCOM dexterous leadership. A “hands-off” manager, Ekeus’s “let-science-lead-the-way” philosophy about running UNSCOM put scientists in the field for the technical work of inspection and destruction while he stuck to the diplomacy, informing the Security Council of their progress and sustaining support for UNSCOM’s operations.17 UNSCOM inspectors lauded Ekeus for his discretion, attentive listening, reasonable command of the technical issues, readiness to innovate, and willingness and ability to navigate political pressures in search of the truth. Ekeus also got very high marks for seeking his inspectors’ counsel, asking the right questions, giving them liberty to do their work, heeding their recommendations, and backing his inspectors in public even if he privately disagreed with them.18 Everyone wanted something from this Swedish diplomat with the shock of white hair, but Ekeus adroitly juggled it all until the timing was right for action.19 One of his juggling tools was language. Fluent in English, Ekeus spoke it with an intonation and phrasing that alternately charmed, informed, or paralyzed his inspectors, the Iraqis, international envoys, policymakers, and the media. Plying this “Swinglish,” “Ekeus could be very unclear if he chose to do so,” said Gallucci, “but very precise when he wished.”20 By all accounts, Ekeus was the right steward for UNSCOM.

To illustrate, Gallucci credited Ekeus with a structural proposal for UNSCOM that found the acceptable middle ground between doing things the typical UN way and the need to send technically qualified inspectors quickly into Iraq.21 A group of international diplomats would advise UNSCOM, while technical experts would do the heavy lifting, inspections. “Splitting the difference, the UNSCOM commissioners were the geographically equitable bit and the small inspectorate was filled with specialists who did the pointy-end-of-the-stick work.”22 Thus the Secretary-General’s plan for UNSCOM called for a headquarters staff of roughly twenty-five people, divided into nuclear, ballistic missile, chemical, biological, and future compliance sections to provide planning and operational support for inspections. As needed, governments would loan technical experts to UNSCOM for the inspections.23 The inspectorate’s tasks were basically to gather and assess information, dispose of weapons and relevant facilities, and monitor and verify compliance.24 Otherwise, Washington’s expectations for UNSCOM were modest, according to Charles Duelfer, who later followed Gallucci as Ekeus’s deputy: “We assumed UNSCOM would resolve some war termination issues temporarily and that its activities would keep sanctions in place, sort of kicking the rock down the road, which was the traditional U.S. approach with Iraq.”25

IRAQ’S INITIAL DECLARATIONS

Meanwhile, Saddam was also banking on UNSCOM to be short-lived. As elaborated further on, Saddam’s inner circle concocted a scheme to dupe the UN’s inspectors an...