![]()

Part One

Defining Islands and Isolating Definitions

![]()

1

Defining Islands and Isolating Definitions

DEFINITION

Horizon . . . f[rom] horos, [meaning] boundary, limit.

—OED, s.v. “horizon”

Generally speaking, a scholarly work begins (or should begin) with asking whether its subject can be defined—and, if so, whether it should be defined overtly—and, if so, whether the definition should be at the beginning, middle, and/or end of the scholarly work or should suffuse it. Most studies avoid defining definition itself, as if they feared becoming bogged down in terminology even before the journey starts.

Thus Islandology cannot afford to avoid defining definition. It is already inescapably concerned, from the beginning, with the “coast”—a term understood in this context as the “cut” where one kind of thing is supposed to begin and another kind is supposed to end (finir). This cut, or limit—Hamlet calls it a bourn, meaning “horizon”1—is crucial to any definition of island. The commonsense understanding of island as “insulet”—meaning “land circumferentially bordered or insulated by water and entirely defined horizontally by its shoreline”2—already raises questions about definition.

The logician John Venn, originator of the Venn diagram (“a group of circles that may or may not intersect according as the logical sets they represent have or have not elements in common”),3 has something to say about such questions of definitional islandness.4 In his Principles of Empirical or Inductive Logic (1889), Venn considers the debate between John Stuart Mill and William Whewell about whether the “discovery” of the elliptical orbit of the planet Mars circumnavigating the sun was a case of induction or deduction.5 He brings up the parallel case where “a navigator sail[s] round an island and then pronounce[s] it to be an island.”6 If circumnavigation alone makes a “land” an “island,” says Venn, then the eighteen members of Ferdinand Magellan’s crew who made it back to Portugal after their three-year voyage should have concluded that the planet Earth was an island. Richard Eden, in the preface to his translation of Sebastian Münster’s Treatise of the Newe India (1553), writes, “The [w]hole globe of the world . . . hath been sayled aboute.”7 One thinks of Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, published in 1873, with its nicely named character Passepartout.

The meanings of most words, not only island, often seem to dissipate a bit around the edges. In Methods of Logic (1952), the philosopher Willard V. Quine claims that the “whiteness of a region in a Venn diagram means nothing but lack of information.”8 A concept, writes the logician Friedrich Ludwig Gottlob Frege in Foundations of Arithmetic (1884),

must have a sharp boundary. If we represent concepts in extension by areas on a plane, this is admittedly a picture that can be used only with caution, but here it can do us good service. To a concept without sharp boundary there would correspond an area that had not a sharp boundary-line all around, but in places just vaguely faded into the background. This would not really be an area at all; and likewise a concept that is not sharply defined is wrongly termed a concept.9

Of this viewpoint of isolation, Ludwig Wittgenstein makes a critique in his posthumously published Philosophical Investigations (1953).10

This way of speaking about groups obtains as well for nations as for words. Thus Johann Gottfried von Herder envisions a nation as a closed autonomous island, each corresponding to a people’s territorial area and linguistic extent11—or so such recent works as Spaces of Culture: City, Nation, World (1999) seek to envision his thought. In fact, Herder knows well that many cultures exist on small islands. He often contrasts the cultural uniformity of large islands with the cultural diversity of small ones. Whether the word island represents a particularly telling locus of thought—where parts become wholes and wholes become parts—is an ancient question. Plato raises the problem of the potential link between islandic geography and thinking when he discusses the waters of the Euripus Strait, the narrows that eventually took Aristotle’s life.12

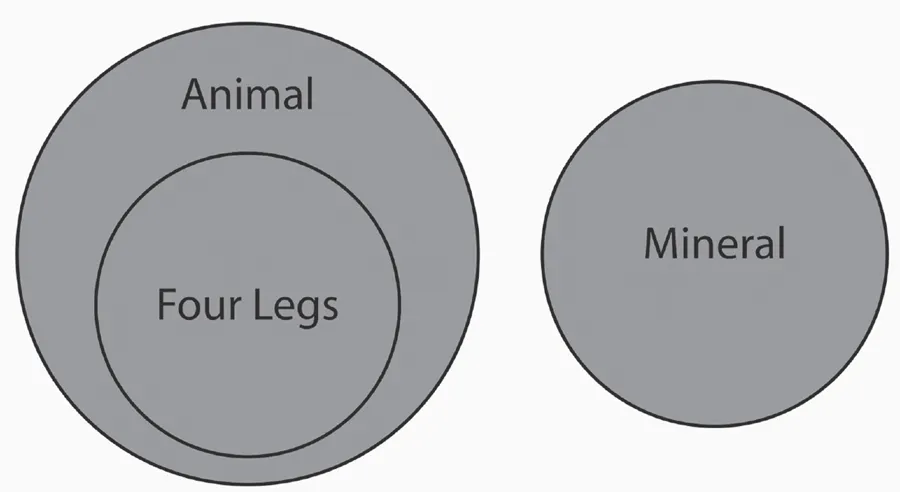

ILLUSTRATION 1 Animal. Four Legs. Mineral. Standard (Leonhard) Euler diagram. Source: Collection Selechonek.

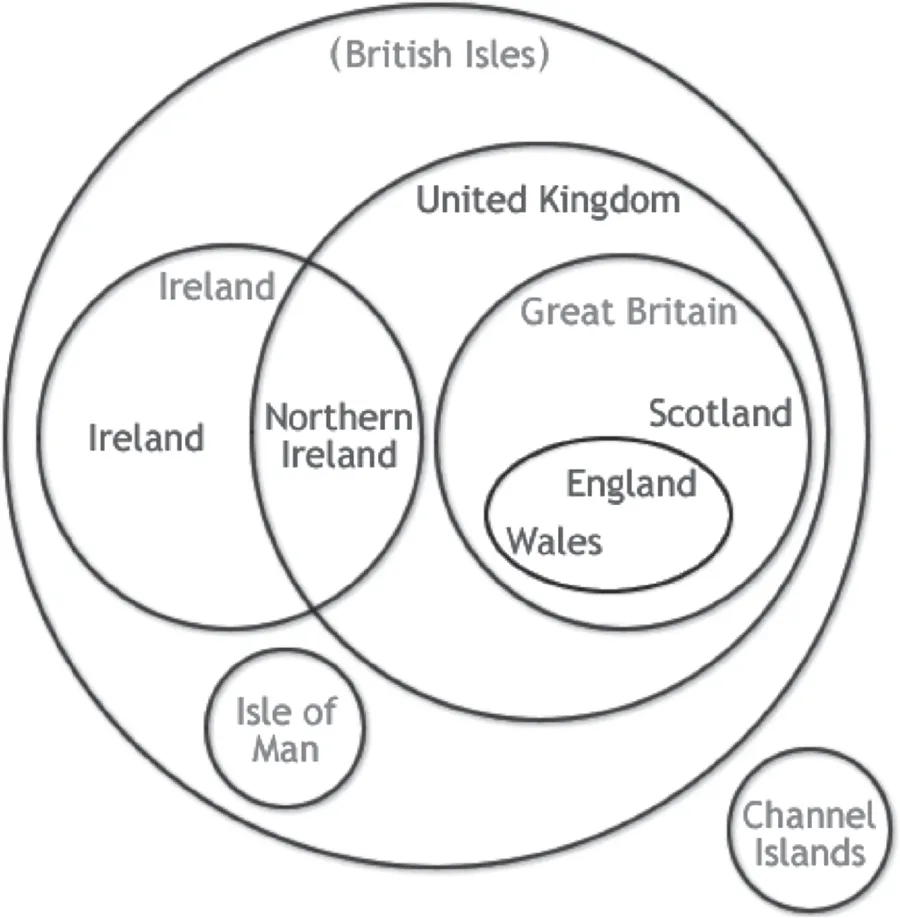

Consider, then, how a Venn diagram presents the cut between a finite group of parts and their wholes (see Illustration 1). Venn illustrates set theory in terms of geographic regionalism. An archipelagic logic shows islands of the British Empire (including the “British Isles”) seeming to match up to islands of meaning13 (see Illustration 2)—an appearance that informs both his essay “On the Employment of Geometrical Diagrams for the Sensible Representation of Logical Propositions” (1880)14 and his book Symbolic Logic (1881).15 Here the geographer’s task of separating island from mainland and one island from another precedes the philosopher’s dialectical ambition to define parts and wholes. It is no wonder that twenty-first-century school-teachers still use a Venn diagram to compare the Sargasso Sea—“a sea within a sea,”16 “the sea with no shores,”17 “a sea without a coastline”18—with the fictional Sargasso Sea of Jules Verne’s science fiction novel Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea (1870).19

If islands constitute an instigating and typical case for philosophical definition, then philosophy and geography are probably interrelated in such a way as to raise questions. Might it turn out to be more than a “mere metaphor” that John Robert Ross, in Constraints on Variables in Syntax (1967),20 with his Chomskyan generative, focuses on the “marooned,” or insulated, location of wh-words in languages? Is it an “accident” that Benoit Mandelbrot poses his question, “How Long Is the Coast of Great Britain?” (1967),21 in terms of the fiction of measurable circumambulation of islands? After all, Mandelbrot’s Fractal Geometry of Nature (1982) links mathematical forms with natural objects in the way of geography, as in his argument that “clouds are not spheres, mountains are not cones, coastlines are not circles, and bark is not smooth, nor does lightning travel in a straight line.”22 Does Venn’s having hailed from the Humber—the estuary on the North Sea where the tidal rivers Ouse and Trent daily reveal and conceal mudflat islands23—suggest how biography can become of formative significance? Or are there other concerns at work in delimiting the intersection of island thinking with thinking in general?

ILLUSTRATION 2 Islands Defined as Venn Diagrams. John Venn’s island diagrams lend themselves to defining nations with many islands or large archipelagoes (e.g., Greece, Canada, and Greater Britain). Source: Collection Selechonek.

Venn’s work was attractive to a Victorian empire then ruling over a great part of the Earth: the British Empire, as he knew it, was the largest in world history. Writes Carl Schmitt, a Nazi opportunist who set himself up as that empire’s enemy: “It was only by turning into an island, in a new sense previously unknown, that England could succeed in conquering the oceans and win the first round of the planetary spatial revolution.”24

According to the ideology of the “scepter’d isle”25 that was summarized for British readers in Shakespeare’s Richard II, the English “nation” followed a foreign policy of “splendid isolation.” That is what First Lord of the Admiralty Lord Goschen called British policy in 1896.26 Goschen was echoing sentiments from colonial New Brunswick in the “New World,” where people had long regarded Britain as the “Empress Island.”27 The inhabitants of other island-based empires such as Venice and Hormuz did likewise.

John Venn “mapped out” sometimes overlapping logical relations between finite collections of sets in much the same way that his contemporaries mapped out aggregations of imperial holdings. Leonhard Euler put forward the first planar graph theorem28 and laid the groundwork for developments in topology when he solved a mathematical problem represented in terms of bridging islands in the Pregel River at Königsberg, the hometown of Immanuel Kant, who set the terms for modern philosophy.

EPISTEMOLOGY

An Enlighten...