![]()

One

Pinsk (1881–1914)

Formative Factors

In this period, Pinsk was a relatively small city. The Jewish population did not increase as it did in Minsk, Bialystok, Brest, and many other cities. Pinsk nevertheless earned a place of honor on the Jewish map—because of the intensity of its communal life, the city’s pronounced awareness of the needs of Jews in general, as well as its own, and the development of civic institutions. Pinsk was notable for its responsiveness to the continual changing rhythms of the times and for its nationalistic, democratic, and revolutionary agitation. Pinsk retained, to an extent, its heritage of leadership in the Lithuanian Jewish Council, [autonomous central organization of Lithuanian Jewry] alongside the tradition of fervor and confidence characteristic of the Karlin Hasidim.

Many factors, old and new, coalesced to shape Pinsk’s special character: The city’s growth came essentially from within, not from large-scale immigration. This led to the formation of close-knit associations despite class tensions between different groups. Karlin Hasidism had a definite democratizing effect upon the nature of the city and quickened its propensity for unity and action where social welfare was concerned.1 Pinsk was, for the most part, a Jewish city. The Haskalah [movement for spreading modern European culture among Jews], which pervaded Pinsk, was predominantly Hebraist and nationalistic in character, whereas the influence of the Russian Haskalah penetrated primarily after the liberal period of Alexander II (died 1881). After the pogroms of 1648, the city had suffered no disturbances. Because of its geographical location, Pinsk became a center for trade and industry. As a result the number of laborers in the city increased.

Demography

Authoritative demographic data about Russian Jewry is available only from the late 1870s on. In the eighteenth century, large numbers of people “vanished” from official view to evade the tax burden; these numbers rose because of Tsar Nikolai I’s calamitous edict imposing compulsory military service on the Jews. The “disappearances” ceased after the 1874 publication of a manifesto that pledged not to punish the missing if they would reveal themselves.2 In 1879 the Jewish population of Pinsk was said to number sixteen thousand souls. According to the demographic data of 1887, there were 19,017 Jews in the city out of a total population of 22,967 (82.8 percent). In subsequent years the percentage of Jews decreased significantly. In 1897 there were 21,065 Jews out of a total population of 28,368 (74.6 percent). In the years following, the Jewish population continued to increase, but the proportion decreased further. In 1905 the total population of Pinsk was 34,174 people, including 25,136 Jews (73.5 percent). Even so, Pinsk was second among the Jewish communities of Russia in its percentage of Jews. Only Berdichev, whose population according to the 1910 statistics was 78 percent Jewish, ranked higher. In other cities the percentage of Jews was much smaller. By 1913 the population of Pinsk numbered 38,686, among them 28,063 Jews (72.2 percent).3 Even with this decreased ratio, the Jews composed nearly three-fourths of the total population, and the city had a decidedly Jewish character.

The decrease in the percentage of Jews in Pinsk was caused by emigration from the city and by the growth in non-Jewish settlement. The population of non-Jews rose from 3,950 in 1887, to 10,623 in 1914. This cannot be attributed to natural increase alone. The fifteen hundred Christian workers at the railway yards, who were imported from Russia in the 1880s, may be considered new settlers. Many of them doubtlessly arrived with their families. This implies that in the city proper the proportion of Jews was higher than the official statistical data indicates, and at the outbreak of the First World War, the Pinsk population was approximately 80 percent Jewish.

Emigration

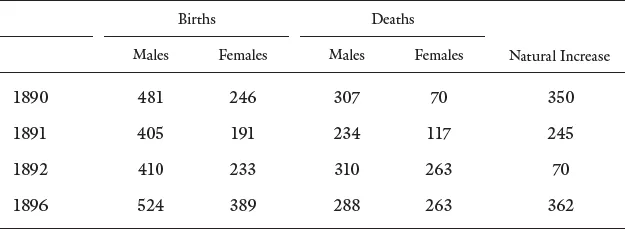

Until 1887 emigration from Pinsk was small compared to the exodus from other places; in any case there is little evidence for it. But from 1887 onward, a fairly high rate of departure is evident. We can estimate the numbers of Jews who left the city between 1887 and 1897. Official figures of natural increase are available for 1890, 1891, 1892, and 1896.

It is difficult to explain the odd variations in the data and the wide disparity between males and females in births and deaths. The data may be inaccurate because a significant number of female births went unregistered, no permit being required to name a female child in the synagogue. Information from the year 1900 shows that the birth rate exceeded the death rate by 787. That year the total population numbered 30,339.4 Accordingly, the rate of natural increase was twenty-five per thousand;5 the annual natural increase among the Jews was at least five hundred people. According to the birth registry and the death registry(metryki), there were 974 births and 410 deaths (220 males and 190 females) in 1900 among the Jewish population; in other words, the natural increase was 564.5. We may assume that if the population had been stable, it would have grown by five thousand people in the decade from 1887 to 1897. In actuality, it increased by only 2,048, despite the fact that Jews came from elsewhere to settle in the city.

TABLE 1.1

Natural increase in the Pinsk Jewish population, 1890–96

Epidemics were rare occurrences, and to the extent that various diseases broke out, they did not claim many victims. In 1893 there was an outbreak of cholera, but in the period from August 1 until January 1, 1894, there were no more than 320 deaths in the entire Minsk district.6 “It is known that in the months of Av and Elul [months of the Jewish calendar, corresponding to July and August], there is an increase in the numbers of the sick among the poor and the children as a result of eating unripe fruit and a surfeit of vegetables and fruits.”7 But these factors could not significantly influence the extent of natural increase.

Emigration prior to 1887 fell into three categories. The first category included people with initiative and practical talents who headed for the larger commercial centers like Kiev and Moscow. The second group, intellectuals living in poverty, headed mainly for various cities in southeastern Russia, where they tried their luck as Hebrew teachers or businessmen. Among this class, some also left for America and Palestine. Most of the emigrants, however, were simply impoverished, and they turned toward America. The Jews of Pinsk were spared the frenzy characteristic of the flight from Russia in the early 1880s because they had not undergone the calamities of the sufot banegev [the pogroms of 1881–1884]. In the latter half of the decade, however, a severe economic crisis buffeted the city. This reached its peak in 1891 and caused progressively increasing emigration to America. An article from 1887 states: “The number of our brothers who leave for America grows with every passing day in our city, too; not only the young make the journey to the New World but families as well.”8 Shaul Mendel Rabinowitsch wrote an article in 1891 describing the plight of travelers on their way west who reached Pinsk by the river route and had to camp temporarily by the railway station. Rabinowitsch’s opinion was that the emigrants did not leave their homes for lack of livelihood but that many had been seized by a kind of mass psychosis. “We see members of our community in the town pick up knapsacks and exile themselves to faraway lands.”9 Relying upon Ha-Maggid’s [Hebrew weekly, influential both in Haskalah and Orthodox circles] description of the miseries of travel reported by a Pinsker, Yisrael Gatsman, Rabinowitsch cautions against emigration to America, remonstrating, “Brothers, you should know it is not only one report which has reached us but hundreds, from all the many wanderers who have left our city.”10 In 1893 the writer again describes the migrants’ camps alongside the river and near the railway, where “more wanderers from our city join them.”11 Wealthy people also left the city. One writer appeals to the “notables of Karlin,” seeking aid for the old-age home. “It is clear to all of us that many of the well-to-do have moved to other cities and the income of the home has declined.”12 The official demographic data from 1890, 1891, 1892, and 1896 show a pronounced decrease in the Jewish population between 1892 and 1896. In 1890 there had been 26,635 Jews in the city (13,456 males and 13,179 females). In 1891 there were 26,070 Jews (13,213 males and 12,857 females). In 1892 there were 26,796 Jews (13,582 males and 13,214 females). And by 1896 there were only 21,819 Jews (10,375 males and 11,444 females). In the course of the four years from 1892 to 1896, the Jewish population of Pinsk had decreased by 4,975 persons. The 1880s had been years of continued growth of the Jewish population in the city; in the early 1890s, the situation remained stable; in the mid-1890s, the Jewish population decreased dramatically. On the eve of the First World War, the situation returned to that of the early 1890s. The population had again increased and stood at approximately twenty-eight thousand.

The flow of emigration in the first fourteen years of this century, that is up to the First World War, was not insignificant, although in 1902 one source notes that “there are not many emigrants from Pinsk.”13 No doubt the fear of military conscription during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) prompted many to flee to America. In April 1904 Chaim Weizmann writes from Pinsk: “People speak of nothing but emigration; it is discussed in all strata of society, everyone longs to leave.” The reason for this, he believes, is the great poverty and the fear of pogroms.14 An article from October 1904 states:

It is difficult to describe our situation today. Women part from their husbands who go off to war; half a year has gone by, and mothers and sisters wait weeping at the post office, in vain, for a letter from their sons and brothers. Others stand there and wait for a letter from “theirs” in America and for nothing. The agents [travel agents] swindle ruthlessly and suck the poor dry. On Saturday, October 16, a crowd assembled—women whose husbands were returned from the border—and broke all the window panes in the agent’s house.15

A 1905 news item from Pinsk reports that many Jewish families are about to emigrate.16 An article from March 1906 states: “Emigration from Pinsk is very high; not a day goes by that several families do not leave for America or England; apparently the emigration will increase after Pesah [Passover].”17 In 1905 Grigory Luria took it upon himself to serve as an unofficial Pinsk representative for the information office of the ICA [Jewish Colonization Association, founded in 1891 by Baron Maurice de Hirsch] center in Petersburg, to provide information to prospective emigrants.18 ICA established an emigration information office in Pinsk in mid-1909. During the first eighteen months of its existence, that is, until the end of 1910, 969 people applied to the office, approximately one-third of them people with families. Ya’acov Kantor, reporting on this, is of the opinion that 90 percent of the applicants, whose number reached at least 1,350 individuals, emigrated from the city. Kantor also points out that many others, who had not made inquiry at the office, emigrated; he assumes that within that eighteen-month period, eighteen hundred people left the city, in other words, twelve hundred people per year.19 All departed for North and South America. Many Bund [General Union of Jewish Workers in Lithuania, Poland, and Russia] and Sionisty Sotsialisty [movement combining Zionism and Socialism; see Chapter Two] activists fled from Pinsk, as from other revolutionary centers, after the failure of the 1905 revolution. The biographies of Pinskers in America attest to this.20

Emigration had many causes and was a problem of broad dimensions. In Pinsk it now became a public question as well. On October 20, 1909, a meeting was held to prepare for a Jewish congress, dealing with issues of emigration, which was to take place in Vienna in 1910. The meeting resolved to send delegates to the congress at the community’s expense. A decision was made to form emigration societies in the city and its vicinity to implement resolutions passed at the congress. A nine-member committee was selected.21 Many of the emigrants were young people, who were of course more mobile. There were some who fled for fear of the police and others to avoid induction for four years of army service, leaving their parents to pay a fine of three hundred rubles as punishment for their failure to report. The migration of the young people left its mark in the marriage and birth registries. Two hundred fifty-three marriages, 974 births, and a natural increase of 564 individuals were registered in 1900. But in 1910 only 176 marriages, 749 births, and a natural increase of 419 were registered; and in 1914, only 162 marriages, 630 births, and a natural increase of 240 individuals.22 Although the reliability of the birth data is dubious, there is no reason to doubt the accuracy of the marriage registrations, which show a real decline. Surely one factor in the decrease in the number of weddings in 1914 was the outbreak of war that year.

Despite these factors—emigration, escaping revolutionaries, and young men fleeing for fear of induction into the army—the Jewish population in Pinsk increased between 1897 and 1914, from 21,065 to 28,063 people. The explanation lies in the relocation of many Jews from the towns and villages in the vicinity to the city. A large network of villages with Jewish residents existed in the countryside around Pinsk. Sixty-two villages are listed in the document, which records the sale of hametz [foodstuffs forbidden for Jews to possess during Passover] in Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Volk’s rabbinical court in 1909. The residents of the hamlets may have been drawn to Pinsk by fear of pogroms or perhaps by the possibility of proper education for their ...