![]()

1

Pre-Oil Urbanism

The Settlement of Kuwait

Kuwait was established in 1716 as a predominantly urban society. During the “tribal outbreak” of the eighteenth century, tribes from central and southern Arabia migrated toward the northeast coast of the peninsula to escape severe drought and famine.1 One group of families who migrated together, known collectively as the Bani ‘Utub,2 came from the Najd-based Anizah tribal confederation and had been settled cultivators prior to their migration to the coast.3 When they reached the head of the Persian Gulf around 1716, they found a spacious bay with a nearby freshwater supply. There was no existing town or significant community settled in the area; aside from a few fishermen’s huts, the only physical structure of significance was a fort (kut) of the Bani Khalid tribe, which had seized control of eastern Arabia from the Ottomans in the 1660s. The ‘Utub set up their new settlement on a small hill known as Tell Bhaiteh, which faced the Bani Khalid’s kut (for which Kuwait is a diminutive meaning “small fort”).

Within less than a hundred years this cluster of families grew into “a thriving commercial settlement” whose residents engaged in fishing, pearling, shipping, shipbuilding, and trade.4 Kuwait’s auspicious location in the northwest corner of the Gulf and its enviable natural properties fostered its growth into a vibrant port and regional entrepôt. The area around the town was “of the most barren and inhospitable description, without a tree or shrub visible as far as the eye can reach, except a few bushes which mark the wells, of which the water is particularly salty and bad.”5 The place would have been uninhabitable without its large natural harbor, “capable of containing the navy of Great Britain,”6 which allowed the townspeople to import everything they needed. Kuwaiti merchants imported grain and wheat from Basra, Iraq; piece goods, rice, sugar, spices, and teak for shipbuilding from India; mangrove poles for house-building from east Africa; coffee from the Red Sea region; tobacco and dried fruits from Iran; and fresh water from the Shatt al-Arab river in southern Iraq.7 Because of the importance of trade, Kuwait Town was established as a free port and no customs duties were levied on sea imports until the beginning of the twentieth century. Its strategic position between the Gulf and the deserts of northeastern Arabia made it an important gateway between the sea and the hinterland. The town grew into a chief center of the transit trade linking the transnational Indian Ocean maritime network with the caravan trade extending inland as far as Damascus.8 The town’s proximity to the Shatt al-Arab also gave Kuwaitis access to the fertile river channels of Iraq, and dates from this region became the principal export cargo of Kuwait’s long-distance traders.

According to local tradition, for the first forty years the settlers had no leader but paid tribute to the shaykh, or chief, of the Bani Khalid. When their population increased due to the town’s economic prosperity, the heads of the main families decided that a leader must be chosen to settle all problems and disputes and to protect the town from external attack.9 Many leading ‘Utbi families turned down the job because governing the town would interfere with their maritime trades. The Al Sabah, however—“the poorest of the important families”—agreed to provide a ruler for the town “both for the honor of it and because the opportunity costs for them were very low.”10 Therefore, in 1752 Sabah I was selected for this position.

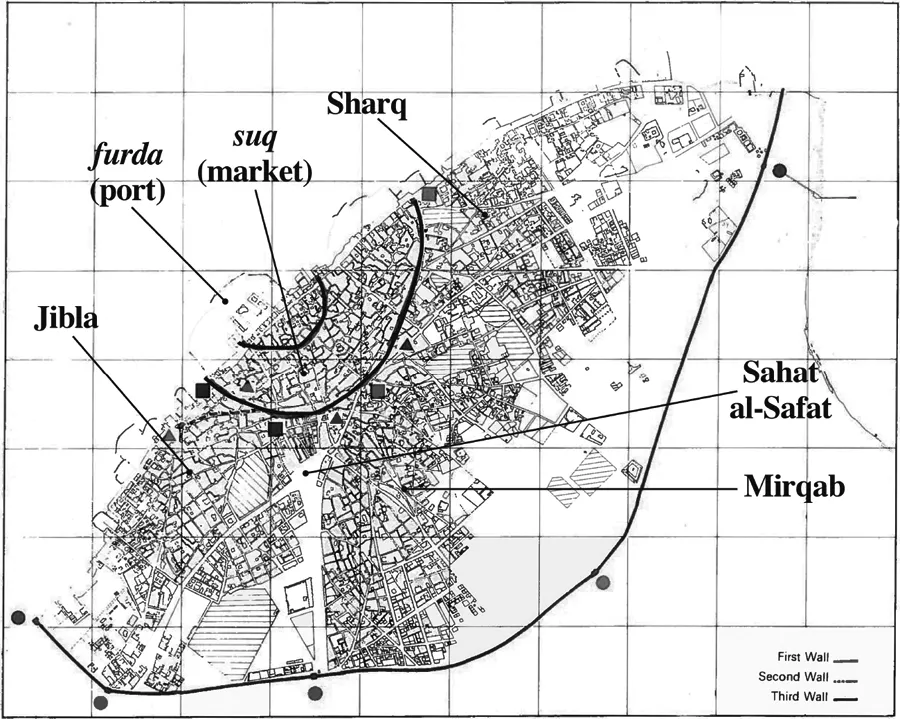

In 1760 Sabah I built a wall around his small settlement, signaling the moment when Kuwait became an independent, viable, and self-sufficient town. Over the next two centuries Kuwait developed from a small coastal settlement enclosed within a dilapidated boundary wall into a city-state with territorial boundaries that, when finally locked in place in 1922, extended well beyond the town’s limits to incorporate expanses of desert. The coastline enclosed within the 1760 wall was approximately six hundred meters long, with an inland depth of around three hundred meters. This small area was unable to accommodate the substantial demographic growth that occurred at the turn of the century, so a second wall was built in 1811 that reflected the extent of the town’s achieved and anticipated spatial expansion. The new wall had a semi-circular shape similar to the first wall, but the length of the town’s shoreline from one end of the new wall to the other was now approximately sixteen hundred meters, and the town had expanded an additional four hundred meters inland. Kuwait experienced a period of unprecedented economic and demographic growth from the 1890s until around 1920 due to a pearling and trading boom throughout the region. This growth may explain why sometime after 1887, when J. R. Povah made the last recorded reference to its existence, the second wall was removed and urban expansion became unbounded.11 Kuwait Town’s population grew substantially during this period. The demand for buildings to accommodate new immigrants increased, leading to a peak in the house-building industry.12 The British Political Agent reported in 1916 that “building operations are in evidence in all quarters of the town, which is rapidly extending.”13 By the time the third wall went up in 1920, it was much longer than the earlier walls and encompassed a significantly larger area. The urban coastline within the new wall had reached 5,600 meters. The total area inside the second wall before it was demolished, after nearly 170 years of settlement, was .724 square kilometers; the area incorporated within the third wall was 7.5 square kilometers—a spatial increase of more than 900 percent within only thirty to forty additional years of settlement (Figure 1).14

FIGURE 1. Map of Kuwait Town showing the three walls, residential quarters, and different morphological sectors. Source: Kuwait Municipality, Planning and Urban Development (modified with labels).

In 1899 Mubarak I signed a protection agreement with Great Britain, although Kuwait still had tenuous ties with the Ottoman Empire. Mubarak pledged not to receive the representative of any other power, nor to cede any portion of his territory to any foreign government or subject without the previous consent of the British government.15 This treaty and those signed with other Gulf rulers “protected the position of local dynasties” because they were signed directly in the names of individual rulers and their successors.16 Unlike in other parts of the Gulf, the British rarely interfered in Kuwait’s internal affairs. But they did largely take control over Kuwait’s external affairs, including establishing its boundaries. In 1913 the British and Ottoman Empires met to settle, among other existing disputes in the region, “the status and limits” of Kuwait.17 They identified the undisputed territory of the Al Sabah as having Kuwait Town at its center and including all areas inside a radius of forty miles in all directions. The tribes in this area were considered loyal to Mubarak because he was able to extract from them the zakat (alms collected from a fixed portion of one’s wealth to help those in need), a key factor in determining the extent of a ruler’s jurisdiction in the desert. In exchange, the tribes received access to the suq, or town market, and nearby water wells, as well as the ruler’s protection along the caravan trade routes.18 Mubarak was further authorized to collect zakat from tribes outside this undisputed territory that were within a radius of 140 miles from the town’s center.19 The agreement was never ratified, however, due to the outbreak of World War I.

Kuwait’s borders were formally established in 1922, as a result of a boundary dispute between Mubarak’s son Salem (r. 1917–21) and Ibn Sa‘ud, the ruler of Najd.20 The conflict between the rulers led to a bloody battle between Kuwait and Ibn Sa‘ud’s militant Ikhwan tribes in Jahra—an agricultural village twenty miles west of Kuwait Town under Al Sabah jurisdiction—in October 1920. It was in this context that Salem ordered the building of a new wall, the town’s third, to protect against attack.21 Though the sur (boundary wall) was never assailed, it was Kuwait Town’s first true fortification. Unlike its predecessors—which had been “more for show than protection” in that they were less than a foot thick, quite low, and dilapidated—the new wall was a real protective barrier.22 As American missionary doctor Stanley Mylrea put it, “For more than three miles stretched the great wall completely shutting off the city from the landward side. . . . Kuwait was now a ‘fenced city.’”23 The path of the new sur forever marked the extent of Kuwait’s urban limits, even after the wall was torn down with the advent of oil (Figure 2). The conflicts with Ibn Sa‘ud also led to the fixing of Kuwait’s permanent boundary with Najd at the ‘Uqair Convention of 1922, during which the boundaries between Kuwait, Iraq, and Najd were defined. In this agreement, which was brokered by the British, Kuwait maintained the area within the forty-mile radius that was delineated in the 1913 Anglo-Turkish agreement but lost most of the area beyond that radius to Najd.24

FIGURE 2. Aerial photo (taken in 1951) showing the permanent boundary of Kuwait Town (later Kuwait City) demarcated by the 1920 sur. Source: Kuwait Municipality, Planning and Urban Development.

Occupying the space between Kuwait’s new urban and national boundary lines were the Bedouin camel- and sheep-herding tribes of the hinterland, and a few small agricultural and fishing villages under Al Sabah jurisdiction.25 Though generally self-sufficient, the tribes and villagers were dependent on the town market to sell their produce and buy supplies. The two largest villages (Zor on Failaka Island and Jahra) were governed by a representative on behalf of the Al Sabah. The rest had no recognized headman, and the Al Sabah ruler dealt with them “through the first inhabitant whose presence he [could] secure.”26 The only revenue the ruler collected from the tribes and villagers was the Islamic zakat and a 2 percent tax on goods taken out of Kuwait Town. By 1922 Kuwait’s city-state status was well established.

Demographic Growth

Kuwaiti society before oil could thus be divided into three distinct categories: urban-mercantile (the townspeople), sedentary-pastoral (the agricultural and fishing villages), and nomadic- and semi-nomadic pastoral (the Bedouin). Members of the latter group continuously settled in the town or villages, thereby adopting new social and economic lifestyles and reflecting the porosity of these social categories.27 Many of the townspeople and practically all of the villagers (such as the Awazem, who settled in Dimnah, or present-day Salmiya) therefore shared lineage with the desert tribes. As A. R. Lindt observed in 1939, because of their shared origins coupled with the close interaction and interdependence of Kuwait’s urban and pastoral populations, “there is not that deep cleft between town-dwellers and nomads which is so great an obstacle to a national unity in other Arab countries.”28 In 1904, John G. Lorimer estimated the fixed population of what he called the “Kuwait principality” to be approximately fifty thousand people: thirty-five thousand inside the town, two thousand in the villages, and thirteen thousand Bedouin.29

The town’s population increased between the mid-eighteenth and mid-twentieth centuries as much by immigration as by natural growth, and this increase paralleled the town’s steady economic expansion. Kuwait’s first period of commercial prosperity came during the Persian occupation of Basra, where the British East India Company’s factory was located, beginning in 1777. Kuwait’s neutral position during the regional conflict kept the town and its desert trade routes safe from molestation. The Company therefore chose Kuwait as a safe and suitable place to divert its desert mail and trade between India, the Middle East, and Europe for the duration of the two-year occupation.30 The experience revealed the small town’s strategic importance as a major caravan trading post, and the shipping potential of its large harbor, which provided satisfactory anchorag...