![]()

Part 1

CONCEPTS

![]()

1

Liberals, Conservatives, and Foreign Affairs

“BIG I” IDEOLOGY: AMERICAN LIBERALISM AGAINST FOREIGN TYRANNY

What are ideologies? Broadly, they are sets of widely held beliefs or theories about how the world works. Economist Thomas Sowell describes ideology as “an almost intuitive sense of what things are and how they work.”1 Like all theories, ideologies simplify. “Ideologies elucidate complex realities and reduce them to understandable and manageable terms,” writes historian Michael Hunt.2 Examples of “big I” ideologies that are the most ambitious in terms of the scope of the world that they explain are Liberalism, Communism, and Fascism.

“Big L” Liberalism seeks to maximize individual freedom. A comprehensive theory of the social world, it celebrates the individual across the major domains of human life: the democratic citizen (politics), the capitalist entrepreneur (economics), and the Protestant believer (religion) with his direct relationship with God.3 Liberalism emerged during the English, American, and French Revolutions, when the “bourgeois” middle classes rebelled against the aristocracy. In The Liberal Tradition in America, Louis Hartz argued that because the colonies lacked a feudal past, American Liberalism was particularly consensual, lacking the divisive ideologies and class conflict of the Old World.4

“Big L” Liberalism sets the boundaries of the thinkable in American foreign policy. All Americans cherish their individual liberties, and will be suspicious of tyrannies of either the right or the left. In a 1917 edition of the Washington Evening Star, Clifford Berryman drew a direct link between World War I and the War of Independence (Figure 1.1). Entitled “Same Old Spirit of ’76,” the drawing depicts Uncle Sam, rifle in hand, proud to fight with our allies against the Central Powers. A flag reading “Liberty Forever” leaves no doubt about Uncle Sam’s purpose: defending Liberty against Dictatorship.

FIG. 1.1. Liberalism vs. Dictatorship (Tyranny of the Right), 1917.

Source: Clifford Berryman, Washington Evening Star, July 4, 1917. Image courtesy of the National Archives. ARC 6011256.

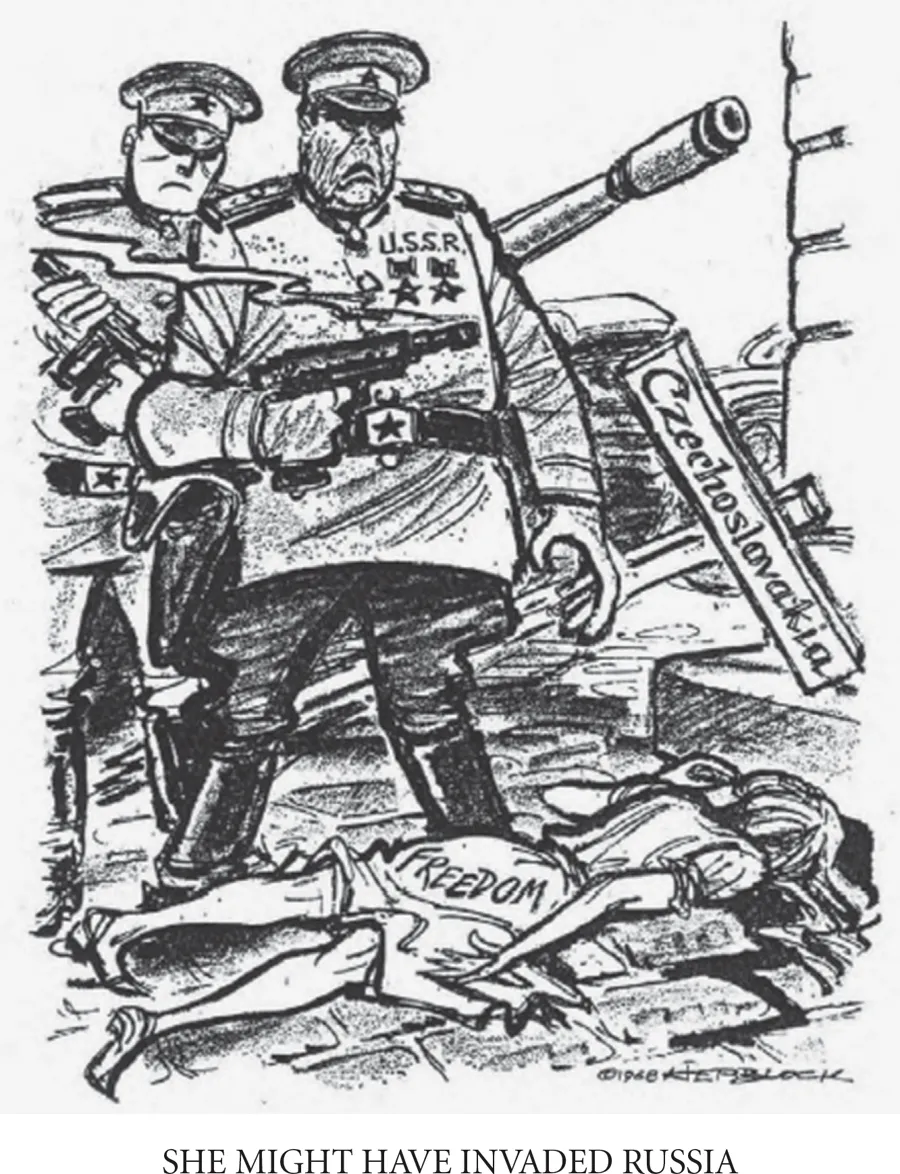

Fifty years later, Herbert Block (hereafter “Herblock”) made a similar point in the Washington Post. In August 1968 the Soviet Union and her Warsaw Pact allies invaded Czechoslovakia, bringing an abrupt end to the Prague Spring. Over one hundred Czechs and Slovaks were killed. Herblock’s drawing (Figure 1.2), sarcastically entitled “She Might Have Invaded Russia,” depicts Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and a henchman holding smoking machine guns over the dead body of a young woman. Leaving no doubt about his (“big L”) Liberal message, Herblock labels the woman “Freedom.”

American Liberalism ensures that Americans will always be wary of tyrannies of any guise, whether fascisms and dictatorships of the right or communisms of the left. This sets broad constraints or parameters within which Americans understand the world. It is not surprising, therefore, that surveys have consistently revealed that Americans feel the coolest towards communist countries like North Korea and China and dictatorships like Iran, and the warmest towards fellow democracies like England, Japan, and Germany (see Figure 0.3).

This book, however, will focus on how the “small i” ideologies of American liberals and conservatives contribute to differences in their worldviews. Within the overall constraints of a shared “big L” Liberalism, American liberals and conservatives maintain consistently different international attitudes and foreign policy preferences. As such, this book differs from a long line of largely historical scholarship emphasizing the influence of shared ideologies on American foreign policy. Against an earlier generation of historians like Charles Beard, who focused on conflicts between different groups of Americans, Richard Hofstadter argued in the early postwar period for a consensus view of American history: “Above and beyond temporary and local conflicts there has been a common ground, a unity of cultural and political tradition, upon which American civilization has stood. That culture has been intensely nationalistic and for the most part isolationist; it has been fiercely individualistic and capitalistic.”5

FIG. 1.2. Liberalism vs. Communism (Tyranny of the Left), 1968.

Source: A 1968 Herblock Cartoon, © The Herb Block Foundation.

Michael Hunt’s pioneering 1987 Ideology and U.S. Foreign Policy followed in Hofstadter’s “consensus history” tradition, arguing that three core ideas have persisted through the years, shaping U.S. foreign policy: nationalism, racism, and a reactionary fear of revolution in defense of property. Subsequent historians have also followed in this “consensus history” tradition, arguing, for example, that a shared ideology of “manifest destiny” or the “warfare state” under-girds American imperialism and militarism.6 Political scientist Michael Desch has also joined this tradition, arguing in his provocative “America’s Liberal Illiberalism” that a “big L” Liberalism at home promotes illiberal foreign policies, such as the George W. Bush administration’s pursuit of global hegemony.7

FIG. 1.3. The demographic correlates of ideology: Being older, male, wealthy, or from the South are associated with being more conservative; greater education or being Hispanic or black are associated with being more liberal.

Note: A regression analysis. * p < .05, ** p < .01, all other p’s ≤ .001. Line thickness in this and all subsequent figures is proportionate to the size of the standardized coefficient. Data source: OU Institute for US-China Issues, 2011.

Hunt is right that inadequate attention has been placed upon the impact of ideology on American foreign policy.8 Unlike Hunt’s focus on shared ideologies, however, this book highlights the foreign policy consequences of ideological differences among Americans.

THE SOURCES OF IDEOLOGY: THE MAKING OF LIBERALS AND CONSERVATIVES

How do Americans differ ideologically? Figure 1.3 displays how seven major demographic characteristics of the American people relate to ideology. In our 2011 survey, being older, male, wealthier, or from the South was correlated with being more conservative, while greater education or being Hispanic or black was associated with being more liberal. While their individual effects were small, each characteristic was statistically significant, together accounting for 8 percent of the variance in an American’s liberal-conservative ideology.

This pattern is consistent with that found in the fall 2010 American National Election Surveys (ANES) data, providing further confirmation that our 2011 YouGov sample is representative of all Americans.9 It is also consistent with previous scholarship on demographics and ideology in America. For instance, the gender gap in ideology first became evident in the 1970s as men became more conservative while women split into two groups, one group becoming more conservative and another more liberal.10 Similarly, a long line of scholarship has explored how and why black Americans are more likely to self-identify as liberals.11 Other scholars have repeatedly shown that greater income is associated with greater conservatism.12 It is also noteworthy that while education and income level were strongly and positively correlated with each other in both our 2011 sample and the 2010 ANES sample (both at exactly r = .45), they correlated with ideology in the opposite directions: greater education was associated with being more liberal, while greater income correlated with being more conservative.

To ensure that the relationships between ideology and the other variables that we examine throughout this book are not the spurious products of these seven demographic variables, we include them as standard covariates or “control variables” in most of our statistical analyses. For instance, when we find in Chapter 4 that liberals enjoy soccer more than conservatives do (β = −.15), we can be confident that it’s not just because Hispanics (β = .13) like soccer more than non-Hispanics and tend to be more liberal, or that older people, who tend to be more conservative, like soccer less (β = −.09, p = .004).

These demographic correlates of ideology, of course, only represent broad tendencies. So what makes some Americans liberals and others conservatives? Social psychologist John Jost has developed a complex functionalist account of the motivational underpinnings of ideology. Specifically, he argues that liberals and conservatives vary systematically in their (1) epistemic needs for certainty, (2) existential needs for security, and (3) relational needs for solidarity.13 Specific psychological predispositions, in other words, lead certain types of people to be drawn to particular types of ideologies.

First, conservatives tend to be less tolerant of ambiguity than liberals, scoring higher on psychological scales measuring the Need for Closure, which taps desires for simplicity and certainty.14 Interestingly, when liberals are put in situations where they are forced to think in more simple ways, such as when they are under cognitive load or even drunk, they tend to become more conservative.15 Liberals also score higher on psychological measures such as the Need for Cognition, which taps the enjoyment of thinking.16

Of the “Big 5” personality traits or domains that psychologists use to describe personality, “openness to new experience” has been the most consistently and strongly associated with ideology: liberals are more open to new experiences while conservatives tend to be more conventional.17 Liberal openness may be tied to their greater need for cognition, while greater conservative conventionalism may be tied to their greater need for closure and certainty. Borrowing from the Ten-Item Personality Inventory, we included two items, “I see myself as open to new experiences, complex” and “I see myself as conventional, uncreative,” in our survey.18 After reverse-coding the latter, they were averaged together to create an “openness” scale, which correlated positively (r = .22) with liberal ideology, replicating earlier work. In a creative study, psychologist Dana Carney and her colleagues made inventories of bedrooms and office spaces, and found that liberals were more likely than conservatives to possess items related to openness, such as a greater number and variety of music CDs, books, maps, and art supplies.19

Second, a large body of scholarship has emerged in psychology demonstrating that conservatives are more fearful and sensitive to threat, attesting to greater existential needs for security. Some lab experiments have revealed ...