![]()

1

OIL, GOD, AND PEARLS

“The people want the reform of the regime!”

“We are brothers, Sunni and Shia, this country is not for sale!”

“No Sunni, No Shia, National Unity!”

—Chants in the Pearl Roundabout, February 16, 2011

The first time I flew to Manama, the capital of the small island state of Bahrain, was in 2008, en route to do fieldwork on the Shia in the Gulf, specifically those in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, which is linked to Bahrain via a causeway. I sat next to a sixty-year-old American from the Midwest, who was heading to the oil fields in Dhahran in the Eastern Province. I had never seen anyone drink so much on a plane—he gave me the impression that this was the last bar before hell and we had better make the most of it. He would be taking a service taxi from the Manama airport across the causeway and into the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, where alcohol consumption is a severe offense. As I was to fly from Bahrain to Riyadh just three days later and then stay there for several months, I thought it was wise to join him, the other expats, and the few Arab professionals in the surrounding rows in knocking back the complimentary whisky and gin while the lights of the oil refineries lining the Gulf flickered below. He had done this trip dozens of times and knew all the oil fields and refineries, from the south of Iraq and Abadan on Iran’s Gulf shore to Kuwait, and down the coast to the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia and Bahrain. There is perhaps no better way to understand the density of the oil fields and the importance of the region to the global oil industry than on a night flight, when the fires of the refineries light up the sky.

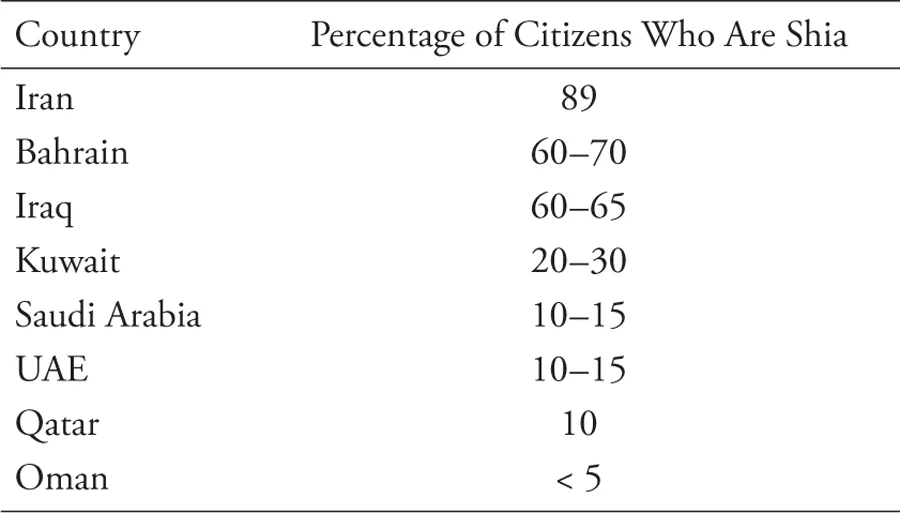

Shia Muslims are strongly represented in the stretch of land that we were flying over, though they make up only a minority of Muslims all over the world—somewhere between 10 to 13 percent of the roughly 1.6 billion Muslims.1 Shia are the majority in southern Iraq, particularly around Basra, where a large part of Iraq’s oil is located and where Saddam Hussein brutally cracked down on a largely Shia uprising in 1991 after the first Gulf War. The Americans watched that crackdown from the sidelines, but when they invaded Iraq in 2003 the Shia of Iraq were brought to power, and the Gulf Shia were able to reestablish old ties with their Iraqi counterparts, through pilgrimage, religious education, business, and intermarriage, and were inspired by the political empowerment of Iraqi Shia. If the Saudi ruling family saw the deposing of Saddam as a historical mistake and an attack on the predominance of the Sunnis in the Middle East, then the Saudi Shia minority in the Eastern Province welcomed the invasion, telling the American diplomats in the country how relieved they were to see Iraqi Shia able to live their religion freely and choose their own political destiny, and that they hoped to achieve the same in Saudi Arabia, too.2

Along the Gulf coast of Saudi Arabia, stretching from Kuwait down to Bahrain, Qatar, and the UAE, up to half of the citizen population is Shia. In Kuwait, the Shia are between 20 and 30 percent of the population. They have long been allied with the ruling family, so many have become wealthy. In Bahrain, Shia make up between 60 and 70 percent of the citizen population, and their case is politically much more sensitive. They would have the potential to overturn the political system both by street protests and democratic means if they were to act as a cohesive group and were allowed adequate representation in a democratic system.3 In Saudi Arabia there are between two and three million Shia, the majority of whom live in the Eastern Province, centered around the two oases al-Ahsa and Qatif.4

Percentage of Shia in the Gulf

NOTE: No official statistics distinguish between Sunni and Shia when estimating the number of Muslims in the Gulf countries. These are estimates for the Shia population in the states with access to the Gulf, based on the available literature and fieldwork across the Gulf.

It was next to these Shia settlements in the Eastern Province in the 1950s that the Americans and their Saudi royal partners established new oil towns—Dhahran, Khobar, and Dammam—as well as a huge compound for the Arabian American Oil Company (ARAMCO), the formerly American and now Saudi-owned oil company. This is where my seatmate on my flight to Manama was headed. As he explained to me, laws were different in those early days, and Westerners could do as they pleased. It was, according to him, the only way one could live in Arabia, in a compound, detached and protected from the Arabs and the desert surrounding them. Compounds and gated communities for American expatriates were introduced to Saudi Arabia by ARAMCO in the 1930s.5 Most Westerners in the Gulf still live in such gated communities, with high walls and armed guards, deeply ignorant and suspicious of what and who is beyond the walls and windows of their homes and offices. Wine made in bathtubs and pool parties with DJs abound.6 And I was about to find this out firsthand, living in a compound in Riyadh.

But first, my seatmate recommended a hotel in Bahrain for me, where he said he had gone for the past few years, one that was reasonably priced, with decent food and a friendly staff. We parted ways in the arrival hall in Manama, where travelers were separated into three groups: one for Khalijis, Gulf citizens whose name derived from the Arabic name for the Gulf, al-Khalij, with passports from the GCC states; one for foreigners, meaning Western expats and visitors; and one for the mainly Indian and South-Asian laborers that arrived with only a handful of belongings to work for a few hundred dollars a month in the burning heat of Arabia as construction workers on the palaces, skyscrapers, and highways or as cleaners, waiters, housemaids, or even soldiers who were relied upon to crush the occasional revolt.7 In 2008, the slogan of Bahrain was still “Business-friendly Bahrain,” and citizens of Western countries were given visas upon arrival, a practice that was made much more difficult after too many journalists, NGOs, and researchers came to investigate the brutal crackdown on protesters in 2011. Perhaps it is needless to say that the slogan was also scrapped after the 2011 uprising, being about as far removed from reality as the slogan that was used to promote the Formula 1 race in 2012: UniFied: One Nation in Celebration.

I took a cab to the recommended hotel. As I got into the taxi, I wondered what the discussion with the driver would bring, and if, like many modern travelers, I would see his opinions as representative of the current state of the country, if they would confirm what I had read previously about the region. From the ring the cab driver wore on his right hand, I knew that he was Shia. The ring, which can be made of various gemstones and has references to the oneness of God engraved, was a tradition first established by the Shia imams. When I asked him about this, he looked puzzled. His typical foreign customers—Western businessmen, oil workers, and soldiers—generally were not interested in local religious and political affairs. He replied with a lowered voice, “Yes I am a Shia, we are the majority in this country, but the ruling family is Sunni. Therefore, we have many problems with them.” I would learn much more about the history and politics of the Gulf Shia over the next years, but even this first conversation made me wonder whether the political marginalization of the Gulf Shia was not a ticking time bomb.

The hotel turned out to be an over-priced high-rise tower in Juffair. I took a room and went down to one of the bars with lower noise levels. Sitting next to me was a German couple. The man was working at the Formula 1 racetrack and she in a local advertising company. He previously had worked at the Hockenheimring racetrack in Germany, but as Formula 1 under Bernie Ecclestone recast itself as a global brand, teaming up with new cash-rich venues such as Bahrain, Abu Dhabi, Singapore, or Shanghai, venues with almost unlimited budgets to bid for F1 races, the man came to seek his own fortune in the Gulf. Bahrain was keen to promote its image as a liberal business center through the F1, a plan that somewhat worked until 2011, when the race was cancelled amidst the mass protests and the following violent crackdown that occurred that year. In 2012 and 2013, the ruling family decided to stage the race again, but the 2012 event became a PR disaster, with foreign media highlighting police brutality and the lack of reform in the desert island.8

After a while, the couple left and I returned to my room to sleep. But the reverberating bass line from the music in the hotel nightclub shook the walls of my über-kitsch room, thwarting any attempt at sleep, and so I returned downstairs. The large nightclub looked rather sleazy, with large mirrors on the walls. Two hundred mainly African American soldiers were dancing to Dirty South rap that a soldier doubling as DJ was playing from his booth high up over the crowd. There were also some female soldiers with slightly intimidating looks, and a few dozen Asian girls who tried to attract the soldiers’ attention and increasingly my own. I ordered some whisky, and soon found myself talking to some of the soldiers, who recounted stories about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the dullness of life at the American naval base in Bahrain, home to the headquarters of the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet. The Fifth Fleet is a key cornerstone for the American army, and is responsible for naval forces in the Gulf, the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea, and the coast off East Africa. Though only a few hours had passed since I had arrived in Bahrain, I had quickly found myself in the middle of the confusing set of strategic interests, resources, wars, and identities that make up the contemporary Middle East. Bahrain and Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province were at the heart of all of this, not least the American hegemonic presence in the region, of which the soldiers with whom I bought rounds of drinks were a most visible sign.

Three years later, on February 15, 2011, when I made another flight to Manama, the world was quite different. Arabs were toppling dictators across the region. Only a few days earlier, Tunisia’s Ben Ali had fled to Saudi Arabia, where he remains in exile and is a vital symbol of how contradictory the Saudi approach to the Arab Spring has been. While 2011 saw protest movements from Chile to the United States, Europe, and Russia, the Arabs were really showing the world how to mobilize and how to bring down dictators, and the Egyptians had just ousted Mubarak from power. Even still, politicians and analysts were busy consoling themselves that Country X was not like Country Y, that Tunisia and Egypt were exceptions in the sea of authoritarian states, that Syria and particularly Gulf countries such as Bahrain or Saudi Arabia could not experience protest movements.9

A day before I boarded the plane to return to Bahrain, on February 14, 2011, one protester had been killed while trying to march to the Pearl Roundabout, a central traffic intersection in Manama. A bit frightened, I asked the two Bahraini women sitting next to me on the plane what they thought, but they replied that I should not be worried as there are protests all the time, and had been in Bahrain for decades. They were referring to the period of sustained popular mobilization from 1994 onwards that did not stop until 2000–2001, when the new King Hamad reached out to the opposition groups, brought them back from exile, and promised profound political reforms, which were supposed to follow a National Action Charter. Incidentally, this charter was approved almost unanimously by a referendum on February 14, 2001. But the promises of fundamental political reform were broken, as Hamad Al Khalifa promulgated a new constitution that significantly differed from the charter Bahrainis had voted for, ensuring that the ruling family maintained a tight grip on power and that the elected half of the parliament had only limited powers. Also in 2002, Hamad Al Khalifa changed the name of the country he was ruling from “State of Bahrain” to “Kingdom of Bahrain,” and declared himself king rather than amir.10 The Bahraini regime had intended to use the ten-year anniversary of this referendum as a propaganda tool with planned festivities and advertisements praising the ten-year reform path posted throughout the country, but this idea backfired.

At Manama airport, all seemed normal, and driving to the hotel was no problem. But when I went to the Arab restaurant on the rooftop of my hotel late that night to grab a bite, I could hear sirens and the sound of helicopters circling over the city, and particularly near the Pearl Roundabout.

I had arranged this research trip weeks before, unaware of a Facebook page that called for a Day of Rage on February 14, 2011. I had wanted to interview veterans of the leftist, Arab Nationalist, and communist movements in the Gulf. But when I met a friend of mine for a late lunch on February 16, he understandably did not want to speak about the history of popular protest and leftist political mobilization in Bahrain. Rather, he wanted to discuss current events. And he wanted to go to the Pearl Roundabout, which was now apparently controlled by the protesters and increasingly being referred to as Tahrir Square, in homage to Cairo’s epicenter of protests. Protesters had gathered at the Pearl Roundabout in the afternoon of February 15, after a second protester had been killed, and his funeral procession on the morning of February 16 was attended by over a thousand people who walked from the main hospital and morgue in Bahrain, the Salmaniya Medical Complex, to a cemetery.11

People rush toward the Pearl monument in Manama, Bahrain, on February 16, 2011. European Pressphoto Agency/Mazen Mahdi.

My friend and his wife took me in their car that evening, and we drove to the roundabout, leaving the old city of Manama to our left and passing the skyscrapers of the financial district. But a few hundred meters from the roundabout in the financial heart of the city we had to stop; the roads were blocked, not by riot police but by a sheer endless mass of empty cars. Thousands had come out to witness what was going on. Unlike in Cairo, where most protesters came by public transport, here most came by car, and this added a whole new disruptive dimension to the protests. When I pointed out to my friend that the mass of silent cars felt like the start of a “car revolution,” he replied with a smile, “This is the Gulf, after all.” We got out of the car and started walking toward the white glowing monument at the center of the roundabout. Illuminated in the night the white pearl monument had an almost magical appeal. In its center stood a sculpture of a dhow—a traditional local sailing vessel—with six arches for its sails, representing the six members of the Gulf Cooperation Council. At the top perched a simulated pearl, as pearl diving had been one of the cornerstones of Bahrain’s economy before the discovery of oil. Approaching the monument we could hear the voices of thousands, the shrieking of megaphones, fanfares, music, engines. What struck me most when we were finally standing on the Pearl Roundabout was how relaxed everyone seemed to be. There were thousands of people on the roundabout, and two had been killed trying to reach here, but on that evening of February 16 it felt like the most natural thing to bring your family to a demonstration in the heart of the capital. Within a few hours, protesters had already set up tents, screens, makeshift kitchens, medical centers, mobile phone charging stations, and a podium for speakers.

We first went to see my friend’s colleagues, a few dozen elderly men in a large tent where all the different leftist opposition groups were gathering. For decades they had been trying to “liberate” Bahrain. Britain had been the colonial power in the Gulf since the late eighteenth century, and it entered into a treaty relationship with the Al Khalifa in 1820, which recognized the Al Khalifa as rulers of Bahrain. Britain also established a Royal Navy base in the country, the premises of which were taken over as the base for the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet at formal independence in 1971. So while the leftists had long fought an a...