![]()

One

“Metropolis of Jews’ Streets”

Shapes of Prague Memory in Jewish Town and Jewish Time

To recover the shapes and rhythms of the urban enclave into which communal memories of Prague’s Jewish population were inscribed requires a leap of carefully informed imagination, a look beyond the twentieth-century caesurae of Holocaust, mass emigration, and Communist regime, and past the radical alteration of the built landscape undertaken as part of the turn-of-the-century renewal project. Most buildings were leveled, the layouts of streets changed beyond recognition.1 Documents and objects collected in the Jewish Museum inspired by the reconstruction for the sake of twentieth-century memory also provide tools for uncovering earlier generations of Prague Jews’ memories of their own, still more distant past. Through such texts we seek to recreate, as much as possible by listening to their own words, how Prague’s Jewish Town looked to those who inhabited it in previous centuries, particularly when that appearance matters to understanding how they remembered their local past (Figure 1.1).

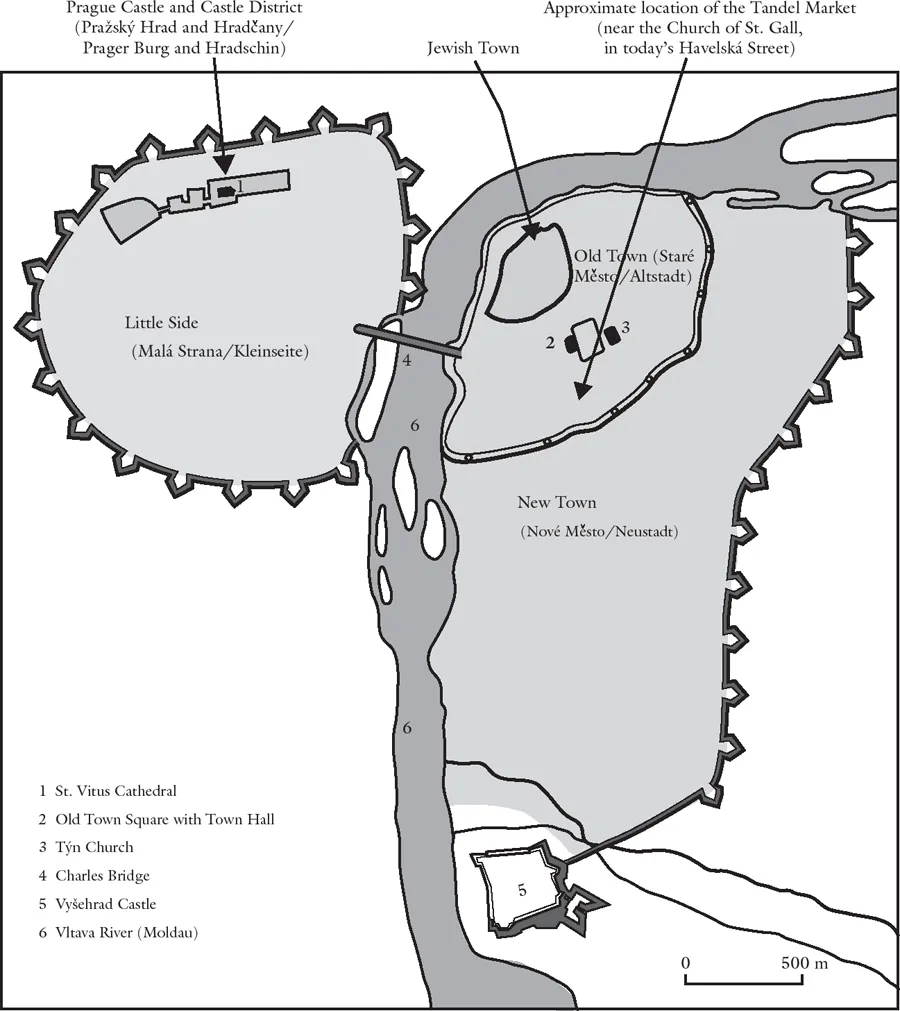

Jews lived, as did most such early modern European urban communities, in a distinct neighborhood known as the Jewish Street, Jewish Town, or, at the pen of historian David Gans in his 1592 Hebrew chronicle Ẓemaḥ David, a “metropolis” of multiple streets (kiryat ḥuẓot hayehudim).2 As opposed to other cities, however, Prague was not a single municipal entity but was made up of three—and later, four—separate towns, autonomous until their 1784 unification, spanning a bend in the Vltava River (Moldau): the Old Town (Staré Město, Altstadt), the New Town (Nové Město, Neustadt) on the river’s right bank, the Little Side (Malá Strana, Kleinseite), and, finally, the additional Castle District (Hradčany, Burg), surrounding the famous Prague Castle (Pražský Hrad)—begun in the ninth century, its St. Vitus Cathedral, its spires completed in the twentieth—on its left (Figure 1.2). The heart of Jewish life, from the late twelfth century on, was centered in the approximate area of today’s Jewish Town, also known as Josefov, wholly subsumed, geographically and politically, by the Old Town surrounding it.3 Sometimes referred to as “Fifth Town,” the Jewish settlement was at once a part of the Old Town and separate from it, at times almost on a footing with Prague’s other separate towns, and yet never quite so.4

Figure 1.1 Antonín Langweil, cardboard model of nineteenth-century Prague, view from south of the Old Town Square, with the Jewish Quarter in the background in the upper left (and continuing off map). To the immediate east (right, in the photo) of the square is the Týn Church, to the west (left), the Old Town Hall. The Marian column arising from the center of the square was erected in 1650 and destroyed in 1918. Courtesy of the City of Prague Museum.

Prague’s Jewish Town was an integral part of the European Jewish settlement concentrated in the Rhine Valley and northern France in the tenth and eleventh centuries, the cradle of a region that came to be known by the biblical name, Ashkenaz. Political regimes that governed Czech Jews from the fifteenth through the early eighteenth centuries included pre-Lutheran non-Catholic Christians, the curious polymath Emperor Rudolf II, and later Habsburg representatives of fervent Catholic renewal, striving for absolute rule. This single Jewish community and its memory stood at these many crossroads, each imparting aesthetic sensibilities, social structures, religious assumptions, and spiritual insights. Understanding their development requires a chronological context as well.

Figure 1.2 The autonomous towns of Prague, circa 1650. Period maps may be found through the Czech-language website of the Prague City Archives at www.ahmp.cz/katalog/, under the heading “Sbírka map a plánů.” (Individual maps can be viewed by clicking on the thumbnail, then on the box, “Zobrazit digitální kopie.”) The “collection of maps and plans” can also be reached through the “search the catalogue” function on the English version of the site, but at the time of this writing, the map pages themselves include Czech only.

“The Eyes of God Are upon It, for Memory and Protection”: Pogrom to Politics in Prague’s Early Synagogues

In 997 CE, Prague Jews, according to an account in early Latin, Czech, and German chronicles, repeated by Gans in Ẓemaḥ David, successfully came to the aid of Duke Boleslav II in a battle against opponents of Christianization, and, as a result, “were famous and glorified in all the land, and they were given permission and assistance to build a synagogue in the Little Side (Malá Strana) in Prague . . .” likely home, in fact, to the city’s oldest Jewish settlement.5 Although the report’s precise details have not been corroborated, a Malá Strana synagogue certainly existed, for it burned to the ground in 1142.6 Across the river and two miles to the south, another early Jewish settlement grew up in the area of today’s New Town, probably along a road leading to a second castle, the Vyšehrad, or High Castle. The scanty memories these two settlements left include a few gravestones, later moved, and the account on which Gans relied. Jewish merchants mentioned by a tenth-century travel writer, Ibrahim ibn Ya′aqub of Tortosa, who was in Prague around 965 CE, may have been travelers themselves, but if they were permanent residents of Prague, they would have lived in the Malá Strana or New Town (Nové Město). So, too, would those Jews killed in Prague during rioting throughout central Europe that accompanied the First Crusade in 1096.7 Hebrew-language memorial lists of casualties of these massacres organized by locale include Prague’s dead among them. The 1096 massacres marked the first significant setback for these oldest Ashkenazi communities and brought about the beginnings of memorial rituals that would become central to their liturgy.8

Nevertheless, the city flourished. In 1160, according to Gans, King Vladislav “brought with him from Italy artists, masons, and built for majesty and glory for the joyfully bustling city of Prague the great, beautiful bridge over the River Moldau, to which none can compare in length, width, height, strength and beauty in all the area of Ashkenaz. . . .”9 This stone bridge helped advance economic development that contributed to Prague’s Jews moving toward the new market center emerging in what is today known as the Old Town (Staré Mĕsto). The first group of Jews to settle there came in the wake of the 1142 fire—history does not relate whether the older synagogue was rebuilt, or whether this settlement may have dispersed entirely at that point—and settled around a synagogue later known as the Altschul (Old Synagogue), on the site of today’s Spanish Synagogue.10 A few blocks to the west, separated from the Altschul since 1346 by the Church of the Holy Spirit, another settlement emerged around a new synagogue. Centuries later, when a third synagogue was built, this one came to be known as the old New Synagogue, the famous Altneuschul (Old New Synagogue).11

Despite medieval Prague Jews’ royal privileges and generally peaceful relations with their Christian neighbors, violence broke out periodically. The deadliest massacre of medieval Prague Jews broke out on the last day of Passover in 1389, which was also Easter Sunday: “All of the suffering that has found us” (Numbers 20:14). So Avigdor Kara, expert in rabbinic law and wisdom from non-Jewish sources, began his elegy to the victims, continuing rhetorically: “Can one tell all that has happened to us?” The lament, Et kol hatela′ah (All of the Suffering), entered Prague’s liturgy for an extant minor fast day (17 Tammuz), and later for Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), along with a second composition by Kara and a third drawn from an earlier corpus. Remaining for centuries in the local liturgy, this massacre was thus Jewish Prague’s earliest strong communal memory. It was also commemorated annually elsewhere; in Worms, among the most venerable of the Ashkenazi communities, a list of its victims was read aloud on the day after the massacre’s anniversary, presumably to avoid mourning on the joyous last day of Passover. Kara’s elegy explains that Jews who ran inside the Old Synagogue (Altschul) for protection were engulfed by fire and destroyed along with the synagogue. The rioters, he wrote, “broke into the Old and New Synagogues,” the Altschul and the then Neuschul, spiritual and geographic centers of the Jewish Quarter, continuing:

Bitterly I call out in weakened voice of suffering

For they degraded, burned, tore the holy books

The Torah commanded to us by Moses.12

Et kol hatela′ah goes on to describe looting, desecration of corpses, and even uncovering of long-buried bones in the cemetery. The Altschul itself was rebuilt, and parts repaired yet again after a fire in 1689. In 1867, it was completely dismantled, and the new Spanish Synagogue built in its place.13 Records of the Altschul’s appearance, foundations, and furnishings were not kept, so while Kara’s lament, recited annually, provided later Prague Jews with a memory of the Altschul and the atrocities experienced there, very little survives to tell what memorials might once have existed within its walls. One exception involves events of centuries later; Judah Leib’s Milḥama beshalom states that during the Swedish siege in 1648: “They fired [artillery] also onto the roof of the Altschul, from all directions, and the weight [of the munitions] was more than 40 ‘liters,’ and the Jews left the depressions they made to preserve as a memory on the sanctuary of the Lord.”14 Memory was, in this case, literally pounded into the outside walls.

Legend regarding the New Synagogue (today’s Altneuschul) held that blood spattered on its walls during the 1389 massacre remained there as a memorial, the synagogue building a venerable witness to its own history.15 This tradition associating memory of the medieval pogrom with one synagogue in particular is probably linked to its later importance. By the late sixteenth century, the former New Synagogue, then known as the Great Synagogue, had surpassed the Old Synagogue (Altschul) as the center of local Jewish life.16 The ground where broad, boutique-lined Pařížská Street now stands was then crowded with buildings, a few narrow alleys running between them. The Altneuschul dominated its surroundings, one of a few freestanding buildings in the Jewish Quarter; a small courtyard abutted its eastern façade. This relative isolation and its stone construction allowed it to survive catastrophic fires that destroyed much else.17 Its physical endurance and central role in communal affairs lent weight and staying power to memories it embodied.

Kara was also associated, in a short early fifteenth-century Hebrew chronicle, “Gilgul bnei Ḥusim” (Hussite Cycle), with the Bohemian Christian reform movement whose founder, Jan Hus, is still today a symbol of Czech nationality and independence (a statue of him occupies a prominent place in Prague’s Old Town Square).18 Hus was a priest and reformer in late fourteenth- and early fifteenth-century Prague, opposing indulgences and icons and supporting translation of the Bible into the vernacular Czech.19 Various Hussite denominations that flourished after his death at the stake as a heretic in 1415 were vigorously opposed by Catholic crusading armies sent from neighboring countries. Among charges against the Hussites was that of “Judaizing,” adopting customs similar to or inspired by Jewish theology or practice.20 The Hebrew chronicle gave this accusation a Jewish twist, claiming that Kara had taught Judaism to Czech King Wenceslaus IV (1378–1419), from whom Hus learned its tenets. While the direct association of Kara with Hussite theology is most likely imaginary, Jews may have seen the internal Christian attack on Catholic practice as grounds for hope of mass Hussite conversion to Judaism, a yearning reflected, according to one scholar, in another of Kara’s songs, “Eḥad yaḥid umeyuḥad” (One, Unique, and Distinct).21 Although later generations, while continuing to sing the song, generally forgot its connection to Hus and Hussitism, and the chronicle, originally appended to a widely read book of customs, ...