- 155 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tweeting the Environment #Brexit

About this book

The level of politicisation of the environment has been low in the UK. Economic concerns outweigh environmental ones in political debates, public policies and political agendas. Can the rise of social media communication change this situation?

Tweeting the Environment #Brexit argues that, although limited by the dynamics of the British context, the technological affordances of Twitter enabled social actors such as the Green Party, ENGOs, and their associates to advance their political and green claims in order to mobilise voters before the 2016 EU referendum and to express their concerns in order to change environmental politics in the aftermath.

The interdisciplinary research employed a combination of big data applications such as ElasticSearch and Kibana and desktop applications such as Gephi and SPSS in analysing large-scale social data. Adopting an inductive and data-driven approach, this book shows the importance of mixed methods and the necessity of narrowing down "big" to "small" data in large-scale social media research.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

The level of politicisation of the environment has been low in the UK. Environmental concerns, although becoming increasingly prominent in public discourses, are always outweighed by concerns over economic growth or other materialist matters such as immigration (Carter, 2015; Hobolt, 2016; Pogorelis, Maddens, Swenden, & Fabre, 2005; Spoon, 2009). Apart from the poor environmental1 record of British politics, insufficient media attention to environmental issues and concerns during political events such as elections is also part of this tradition (Boykoff et al., 2018; Brandenburg, 2006; Schmidt, Ivanova, & Schafer, 2013). Over the recent decade, however, the world has witnessed a growing tendency for social actors to express their environmental concerns and demands on social media platforms. The blossoming of social media communication complicates the state of environmental communication and prompts a question – what is the capacity of social media for helping promote environmental concerns in public discourses and increase the level of politicisation of environmental issues in the UK?

This question is underexplored in the existing literature on environmental politics and social media communication. Most environment politics studies focus on examining the state of environmental issues in government policies, the manifestos of political parties and political debates as well as the development of the Green Party, environmental groups and organisations (see for example Brandenburg, 2006; Carter, 2007; Carter, 2015; Carter, Ladrech, Little, & Tsagkroni, 2017; O’Riordan & Jordan, 1995; Rüdig & Lowe, 1986; Spoon, 2009).

Studies of environmental communication on social media tend to explore the way social media is used by ordinary users during particular situations such as disasters or environmental campaigns, the social media strategies of particular social actors such as the Green Party or Environmental Non-government Groups (ENGOs), or social media discourses on specific environmental topics such as disasters, climate change and environmental movements or campaigns (see for example Autry & Kelly, 2012; Binder, 2012; Hutchins, 2016; Kireyev, Palen, & Anderson, 2009; Li et al., 2016; Takahashi, Tandoc, & Carmichael, 2015).

While existing studies seldom combine the foci of these two fields of research, scarce scholarly attention has been paid to social media discussions on environmental issues in relation to political events such as elections or referenda and their implications for environmental politics. The study of this topic, nevertheless, can offer something important. It sheds light on the role of social media in shaping environmental politics. It offers a prism to inspect the level of politicisation of environmental issues in these discussions and in related social contexts.

The book addresses the above-mentioned underexamined question through an inductive exploration of Twitter discourses and networks about environmental considerations in the discussions about the UK’s European Union (EU) referendum in 2016 and its aftermath. In the referendum, British voters voted to leave the EU by a narrow margin of Leave 51.9% versus Remain 48.1%. This outcome shocked the world; and it is producing profound impacts on Britain, Europe and the world. The environment, which is an important aspect of contemporary politics (Carter, 2007), is particularly prominent in the relationship between the UK and the EU. The role of the EU in establishing environmental standards as an institutional regulator for its member countries has increased public acceptance of European integration (Carrubba & Timpone, 2005; Hix & Marsh, 2007; Hooghe & Marks, 1997; Prosser, 2016). The UK’s membership of the EU has led to the integration of domestic and EU environmental policy in the UK (Lowe & Ward, 1998). Given that environmental issues have been a pivotal justification for the UK’s EU membership, if the environment was prioritised over other materialist issues such as the economy and migration in the referendum campaign and in the minds of voters when they were considering their votes, environmental aspects should have been crucial for the referendum. In spite of their importance, during the referendum campaign, environmental issues were largely missing in the coverage of traditional media, in political debates and in the considerations of voters in the UK (Deacon, Downey, Harmer, Stanyer, & Wring, 2016; Hobolt, 2016).

Twitter, one of the most successful social networking sites, offered an alternative media platform for discussing specific topics during the referendum campaign. On Twitter, users can send one-to-one and one-to-many short2 messages to their followers and receive messages from the ones they follow. They have the freedom to choose who they want to follow and establish their own circles through following, retweeting and other interactions. A number of interesting questions arise for this study: What discourses were constructed in tweets on the environmental aspects of the referendum? How were users connected to one another in this environmental communication? What social actors greatly influenced the discourses and networks and how? What do the discourses, networks and the roles played by social actors suggest about environmental politics on Twitter and in the UK? The answers to these questions contribute to our understanding of social media communication as well as environmental politics.

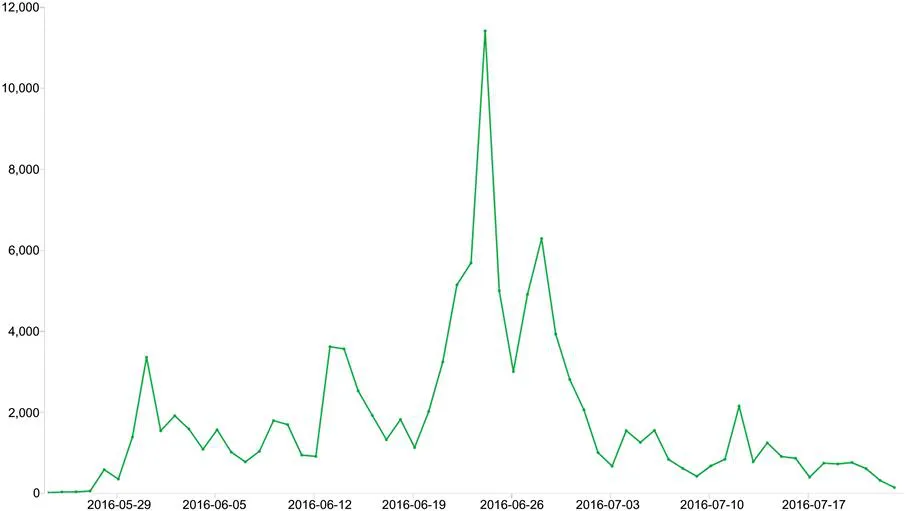

The study reported here draws on a computational discourse and network analysis of 112,298 related tweets collected in real time and archived by using the Twitter Streaming Application Programming Interface (API) between 24 May and 23 July 2016. The data include the tweets that were open to the public and contained any of the seven hashtags, i.e. ‘#Referendum’, ‘#VoteLeave’, ‘#VoteIn’, ‘#EUref’, ‘#VoteOut’, ‘#VoteStay’ and ‘#Brexit’ within the two months surrounding the referendum. We consider that the use of hashtags in tweets indicates a strong intention on the part of users to link their tweets to the topic of the referendum, and therefore, these tweets are most relevant to the studied topic. A total of 31,667,587 tweets were stored in the general dataset. We then followed the literature on environmental discourses and used the following keywords to filter the general dataset: ‘environmental’, ‘environment’, ‘climate’, ‘energy’, ‘polution’,3 ‘pollution’, ‘ecological’, ‘ecology’, ‘carbon dioxide’, ‘global warming’, ‘CO2 emission(s)’, ‘green’, ‘natural resources’, ‘greenhouse’, ‘gas emissions’, ‘gas emission’, ‘biodiversity’, ‘natural disasters’, ‘natural hazards’, ‘acid rain’, ‘resource shortage’, ‘wildlife’, ‘nature reserves’, ‘habitats’ or containing the hashtag: ‘nature’. Only environmental tweets that contain any of the keywords (hashtag) were included. Tweets including some keywords such as ‘Brexit environment’ or ‘political climate’ or ‘Philip Green’, but not suggesting topics about the environment were removed; the rest of the tweets were saved in a separate dataset for further analysis. There are 112,298 environmental tweets sent by 35,761 users in the dataset (referred to as environmental data or dataset in the remainder of the book). However, these tweets accounted for a mere 0.35% of all 31,667,587 tweets about the referendum. Other topics such as immigration or the economy received much more attention from users in the general dataset. For example, the number of tweets mentioning the topic of immigration4 (891,843 tweets in the general dataset) is about eight times the number of the total environmental tweets, while that of the economy5 (2,846,045 tweets) is even more than twenty-five times greater than environmnetal tweets. Such a low proportion of environmental tweets suggests the marginalisation of the environmental aspects of the referendum in Twitter communication. The trend over time of the environmental data can be seen in Figure 1, which shows the discussions reached a peak on 24 June 2016.

Figure 1. Daily Trend of Environmental Tweets One Month Before and After the Referendum (x-Axis: Dates; y-Axis: Number of Tweets).

The research adopted an innovative methodological approach to inductively analysing ‘big’ social media data6 (see detailed discussions about our methodological approach in Chapter 9). Using mixed methods (a detailed discussion of research methods and procedures can be found in Chapter 9; see Chapter 6 for a discussion of social network analysis), we analysed not only the content and networks of social media discussions but also the role played by key social actors in these discussions and the social networks formed around them. In so doing, we aimed to develop a ‘thick’ analysis of social data, borrowing Geertz’s term (Geertz, 1973), so that we could gain an in-depth insight into the relationship between Twitter and environmental politics. Here, a ‘thick’ analysis means that we identified quantitative patterns in social media data on the one hand, and on the other hand, qualitatively interpreted the meanings of the patterns and theorised them through establishing connections between the patterns and social dynamics about environmental politics in context.

We achieved the ‘thick’ analysis in our exploration of the data, using chosen computational applications, which mix big data applications such as ElasticSearch and Kibana and desktop applications such as Gephi and SPSS. The major difference between the two is the former is designed to operate on a distributed environment such as clusters of multiple nodes (machines/computers), while the latter is only run on a single machine/computer and their scalability and computing ability is limited. Therefore, the former is much more scalable and performs better than the latter; and meanwhile they are suitable and economic for handling big data. Our endeavour to inductively analyse ‘big’ data was made possible by our strategy to narrow ‘big’ social data down to ‘small’7 social data. Statistically identifying reasoned patterns in ‘big’ social data together with a close-reading of identified and extracted ‘small’ key data enabled us to gain deep insights into Twitter communication on this topic and its link to social contexts and implications for environmental politics. The scale of our data – 112,298 tweets – and the need to conduct social network analysis of the data made it impossible to adopt merely conventional ways of doing social science research such as content analysis. Therefore, we turned to the help of computational applications so as to quantitatively and statistically analyse the ‘big’ data. However, we needed to narrow down the ‘big’ data to a scale so that we were able to handle the data manually and gain an inductive understanding of the data; such data should nevertheless be meaningful, i.e. which is the key data in the environmental dataset that can be further developed to tell a significant story and leads to a profound understanding of the ‘big’ data. An inductive understanding of the meanings of the ‘small’ but meaningful data helped us interpret the quantitative and statistical patterns identified in computational analysis.

Along with the story being unfolded in our data exploration, we came to understand that the Green Party in the UK,8 ENGOs such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth, their associates, and environmental online media achieved the most prominence in ‘green’ networks on Twitter. The technological affordances of Twitter – the interactions between the infrastructure of Twitter and the users’ use of Twitter – facilitated these green elite users in gaining discursive capacity on the platform. However, they did not succeed in winning the referendum (as suggested by the result), the capacity for which was partly limited by the state of existing politics and environmental politics in the UK and partly limited by the fact that Twitter users may not represent the British electorate (see the discussion in the conclusion in Chapter 4). That is to say, even if they had mobilised voters (on Twitter) to vote for Remain on the basis of green issues, these voters might have been too few in number; at the same time, there might have been more voters who cared more about other materialist issues such as the economy and immigration over the environment. Established British political parties such as the Conservative Party, the Labour Party and the Liberal Democratic Party paid limited attention to environmental concerns in their tweets about the referendum. Overall, the marginalised environmental discourses in the related tweets presented a national perspective and materialist concerns, which were based on economic grounds and focused on the role played by the EU in environmental protections and policies in the UK and even in the world. Pure environmental concerns, i.e. environmental and ecological dimensions such as climate change, global warming, the environmental consequences of fracking, and pollution were barely mentioned, and where they were mentioned, they were only used to support this focus. In this case, Twitter communication shows asymmetrical information flow and sparse networks; and it is geographically bound and has close connections to the British social context, reflecting the extension of British environmental politics onto Twitter. These suggest the influence of social contexts on, and the importance of, geographical proximity, in Twitter communication.

The book comprises eight chapters that are divided into three parts. The first part includes two background chapters. Chapter 2 contextualises the study through discussions of the relationship between environmental issues and politics and between Brexit and the environment. Chapter 3 outlines the overall media landscape within which Twitter resides and identifies key debates in the fields of Twitter communication and environmental communication on Twitter.

The second part has four chapters that address four aspects of our findings. Chapter 4 depicts environmental discourses in tweets and explains the nature of the environmental considerations in the discussions about the referendum on Twitter. Chapter 5 paints a picture of a divided and asymmetrical space where a fragmented elite club and transient communities formed, and where the domination of elite social actors in networks was enabled by the attention given to them by ordinary Twitter users. Chapter 6 presents a social network analysis of the environmental data, in which we examined the attention-based ‘retweeting’ networks (egonets)9 surrounding key social actors (egos). Chapter 7 discusses the tweeting practices and discursive arguments of 15 categories of the 107 influential social actors identified in the egonets in the social network analysis discussed in Chapter 6.

The two chapters in the third part of the book discuss the insights gained from this study as to the relationship between social media and environmental politics (Chapter 8), as well as reflections on social media research and our methodological approach (Chapter 9).

1. By ‘environment’ we mean the natural world where humans, animals and plants live.

2. During the study period, the word limit of Twitter was 140 characters. However, it increased to 280 characters in 2017.

3. This is an intentional misspelling as this word appears in some tweets.

4. Tweets contain one of the keywords ‘migration’, ‘immigration’, ‘immigrant(s)’, ‘migrant(s)’, ‘refugee(s)’, ‘freedom of movement’, ‘free movement’, ‘right to travel’ and ‘mobility rights’.

5. Tweets contain any of the keywords ‘economy’, ‘economic’, ‘pound’, ‘dow jones’, ‘income(s)’, ‘cost(s)’, ‘money’, ‘currency’, ‘tourist(s)’, ‘credit(s)’, ‘job(s)’, ‘financial’, ‘finance’, ‘market(s)’, ‘price(s)’, ‘trade(s)’, ‘business(es)’, ‘worker(s)’, ‘deal(s)’, ‘economist(s)’, ‘wage(s)’, ‘tax(es)’, ‘shop(s)’, ‘fishing’, ‘farming’, ‘TTIP’, ‘bank(s)’, ‘investment(s)’, ‘propert(y/ies)’, and ‘revenue(s)’.

6. The term ‘big data’ refers to an unprecedentedly large amount of data that often come from different sources, but which may be interrelated. This data grows rapidly and are in various formats, as well as being dynamic and unpredictable (Jin, Wah, Cheng, & Wang, 2015). In this book, our data is not typical big data. By ‘big’, we merely mean the big size of the social data in the dataset. Therefore, we used single quotation mark around big to indicate the difference.

7. In the specific context, ‘small’ refers to small facets that are extracted, derived and reasoned from repository of ‘big’ data. Such facets can provide meaningful data insights for researchers.

8. In the remainder of the book, we use the Green Party to refer to the Green Party and its branches in the UK, unless we specify where it is operated.

9. An egonet is a ‘network based on a particular individual’, which is an ego (Scott, 2017: 74 and 84).

CHAPTER 2

THE ENVIRONMENT AND POLITICS

The growth in global environmental awareness among the public and the rise in environmental movements worldwide shows the increasing political importance of the environment at the international level. However, as in most countries, including the UK, green issues have never been a truly salient political agenda. During elections, concerns over topics such as national economic growth and taxation, almost always prevail over pure environmental concerns, wh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Part 1

- Part 2

- Part 3

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Tweeting the Environment #Brexit by Jingrong Tong,Landong Zuo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Media digitali. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.