![]()

II

APPRAISALS OF THE PLAZA

![]()

6

The Plaza Accord 30 Years Later

JEFFREY FRANKEL

September 2015 marked the 30th anniversary of the Plaza Accord, probably the most dramatic policy initiative in the dollar foreign exchange market since Richard Nixon floated the currency in 1973. At the Plaza Hotel in New York on September 22, 1985, US officials and their counterparts in the other G-5 countries agreed to act to bring down the value of the dollar. Public statements from the officials were backed up by foreign exchange intervention (the selling of dollars in exchange for other currencies in the foreign exchange market).

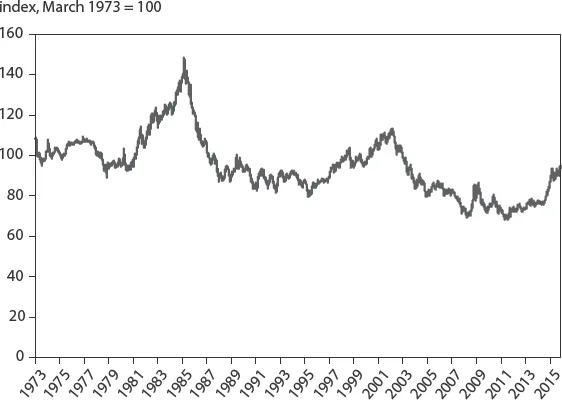

The Plaza is justly celebrated as a high-water mark of international policy coordination. The value of the dollar had climbed 44 percent against other major currencies in the five years leading up to 1985 (figure 6.1).1 Largely as a result of the strong dollar and lost price competitiveness, the US trade balance had sunk to record lows in 1985, spurring congressional support for trade interventions that an economist would have found damaging.

In the two years 1985–87, the value of the dollar fell 40 percent. After the exchange rate turned around, so did the trade balance (with the usual lag). In the end the US Congress refrained from enacting protectionist trade barriers.

Figure 6.1 Trade-weighted value of the dollar against major currencies, 1973–2015

Note: The 1985 peak was far higher than any other point in the last 40 years.

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

The Plaza Accord made institutional history as well. The group of officials that met in New York developed into the G-7 Finance Ministers Group, which has continued to meet ever since.2

Overall, the Plaza was a major public success. It is therefore sobering to realize that the essence of the initiative—a deliberate effort to depreciate a major currency—would be anathema today. In recent years policy actions by a central bank that have the effect of keeping the value of its currency lower than it would otherwise be are likely to be called “currency manipulation” and to be considered an aggressive assault in the “currency wars.” In light of these concerns, the G-7 has refrained from intervening in foreign exchange markets in recent years. In February 2013 the G-7 partners even accepted a proposal by the US Treasury to agree to refrain from unilateral foreign exchange intervention, in an insufficiently discussed ministers’ agreement that one could call the “anti-Plaza” accord (G-7 2013).

The first section of this chapter reviews what happened at the Plaza in September 1985 and during the months leading up to it.3 The subsequent two sections consider the effects of foreign exchange intervention and current worries about currency manipulation and currency wars. The last section considers intervention policy and the dollar as of 2015.

History of the Plaza Agreement

A play-by-play review of the events of 30 years ago can help shed light on the interacting roles of politics, personalities, and chance, in addition to the role of economic fundamentals.

Appreciation of the Dollar in the Early 1980s

The 26 percent appreciation of the dollar between 1980 and 1984 was not difficult to explain based on textbook macroeconomic fundamentals. A combination of tight monetary policy associated with Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker during 1980–82 and expansionary fiscal policy associated with President Ronald Reagan during 1981–84 pushed up long-term interest rates, which in turn attracted a capital inflow and appreciated the currency, just as the famous Mundell-Fleming model predicted would happen.

Martin Feldstein, then chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, popularized the “twin deficits” view of this causal chain. As a result of the fiscal expansion—tax cuts and increased spending—the budget deficit rose (and national saving fell). As a result of the strong dollar, the trade deficit rose. The budget deficit and trade deficit were thus linked. The exchange rate in this view was not the fundamental problem but only the natural symptom of the monetary/fiscal policy mix, the channel through which it was transmitted to the trade deficit (Council of Economic Advisers 1984, Feldstein 1984).

Some trading partners expressed concerns about the magnitude of the dollar appreciation. The French, in particular, favored intervention in the foreign exchange market to dampen such movements. But Treasury Secretary Donald Regan and other administration officials rejected the view that the US trade deficit was a problem, arguing that the strong dollar reflected a global vote of confidence in the US economy, and opposed proposals for intervention in the foreign exchange market to bring the dollar down. Their policy was benign neglect of the exchange rate. In the third month of the administration, Under-Secretary for Monetary Affairs Beryl Sprinkel had announced that its intention was not to intervene at all, except in the case of “disorderly markets.” For Sprinkel, a long-time member of the monetarist “Shadow Open Market Committee” and follower of Milton Friedman, the matter was a simple case of the virtues of the free market.

At the Versailles Summit of G-7 leaders in 1982, the United States responded to complaints about excessive exchange rate movements by agreeing to request an expert study of the effectiveness of foreign exchange intervention. When the resulting Jurgensen Report was submitted to the G-7 leaders at the Williamsburg Summit in 1983, the findings of the underlying research were not quite as supportive of intervention as the other countries had hoped (Henderson and Sampson 1983, US Department of Treasury 1983, Obstfeld 1990). The basic argument was that sterilized intervention has no long-lasting effect and unsterilized intervention is just another kind of monetary policy.

Between March 1984 and February 1985, the dollar appreciated another 17 percent. This final phase of the currency’s ascent was more rapid than the earlier phases and could not readily be explained on the basis of economic fundamentals. The long-term interest rate differential peaked in June 1984. Its subsequent decline was in the wrong direction to explain the remainder of the upswing. The US GDP growth rate and trade balance were also moving down—the wrong direction to explain the continued dollar appreciation. At the time some economists argued that the foreign exchange market was “misaligned” or had been carried away by an irrational “speculative bubble” (Bergsten 1984, Cooper 1985, Krugman 1985, Frankel 1985). Whatever the cause, the trade deficit reached $112 billion in 1984 and continued to widen. Some who had hitherto supported a freely floating exchange rate for the dollar began to change their minds.

Dating the 1985 Shift in Dollar Policy

Between the first Reagan administration and the second, there was a change in policy with respect to the exchange rate: a shift from a relatively doctrinaire laissez-faire policy during 1981–84 to a more flexible policy of activism during 1985–88. An obvious point from which to date the switch is September 22, 1985, when finance ministers and central bank governors met at the Plaza Hotel and agreed to try to bring the dollar down (Funabashi 1988, 9–41; Mulford 2014, 169–72). The Plaza Accord was certainly the embodiment of the new regime. But I would prefer to date the start of the new era from the beginning of 1985. With the inauguration of the second Reagan administration in January 1985, Don Regan and James Baker decided to trade jobs: Regan became White House chief of staff, and Baker took Regan’s job as the secretary of the Treasury (Regan 1988; Baker 2006, 219–20). At the same time, Beryl Sprinkel left Treasury, and Baker’s aide Richard Darman became deputy secretary at the department. David Mulford joined the team in January, as the new assistant secretary for international affairs (Mulford 2014, 156).

At the White House Baker had developed a reputation for greater pragmatism than other, more ideological members of the administration. In his January confirmation hearings, he showed signs of departure with respect to exchange rate policy, stating at one point that the Treasury’s previous stance against intervention was “obviously something that should be looked at” (Destler and Henning 1989, 41–42).

Another reason to date the change from early in the year is that the dollar peaked in February and had already depreciated by 13 percent by the time of the Plaza meeting. Some observers, such as Feldstein (1986) and Taylor (chapter 12 of this volume), argue that the gap in timing shows that exchange rate “policy” had little connection with the actual decline of the dollar, which was determined in the marketplace regardless of the efforts governments made to influence it.

Notwithstanding that official policy did not change until September, however, there are two persuasive respects in which the bursting of the bubble at the end of February may have been in part caused by policy change. First, it was widely anticipated that Baker and Darman would probably be more receptive to the idea of trying to bring down the dollar than their predecessors had been. If market participants have reason to believe that policy changes to reduce the value of the dollar will be made in the future, they will sell dollars today in order to protect themselves against future losses, which will have the effect of causing the dollar to depreciate today.

Second, some intervention was agreed on at a G-5 meeting on January 17—Baker attended the dinner—and did take place subsequently (Funabashi 1988, 10). Surprisingly, the G-5 public announcement in January used language that, on the surface at least, sounds more pro-intervention than was used later in the Plaza announcement: “In light of recent developments in foreign exchange markets,” the G-5 “reaffirmed their commitment made at the Williamsburg Summit to undertake coordinated intervention in the markets as necessary.”

The US intervention that winter was small in magnitude.4 But the German monetary authorities, in particular, intervened heavily, selling dollars in February and March.5 The February intervention was reported in the newspapers and, by virtue of timing, appears a likely candidate for the instrument that pricked the bubble. Baker’s accession to the Treasury in January and the G-5 meeting probably encouraged the Germans to renew their intervention efforts at that time.

One could take a narrow viewpoint and argue that the Plaza Accord should be defined to include only the deliberations made on September 22 at the Plaza Hotel and not other developments in 1985. But my view is that it is appropriate to use the term to include all the elements of the shift in dollar policy that occurred when Baker became Treasury secretary, including other meetings, public statements, perceptions, and—especially—foreign exchange market interventions.

History routinely uses this sort of shorthand: We celebrate 2015 as the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta, even though the precise paper signed at Runnymede in 1215 had no immediate effect in England and did not even bear that name. Versions were reissued in subsequent years (a 1217 version is the one that was first called Magna Carta) and eventually came to represent the principle that the king was bound by law.

We use “Bretton Woods” to denote the postwar monetary system based on pegged exchange rates facilitated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) with gold and the dollar as the international reserve assets. But the system that was agreed at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in 1944 had been negotiated over the preceding two years and did not really come into full operation until some 15 years later (initially the IMF had little role to play and European countries delayed restoring currency convertibility), by which time it was already beginning to break down (as the convertibility of the dollar into gold was increasingly in question) (Steil 2013). Nevertheless “Bretton Woods” is a useful shorthand, like “Magna Carta.” It is similarly useful to apply “Plaza Accord” to the set of changes in policy with respect to the dollar that took place in 1985.

The Plaza Meeting Itself

In April 1985, at an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) meeting, Baker announced, “The US is prepared to consider the possible value of hosting a high-level meeting of the major industrial countries” on the subject of international monetary reform. Similar trial balloons were floated in Congress (Putnam and Bayne 1987, 199). But the other shoe was yet to drop. Monetary and exchange rate issues were not extensively discussed a...