This is a test

- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

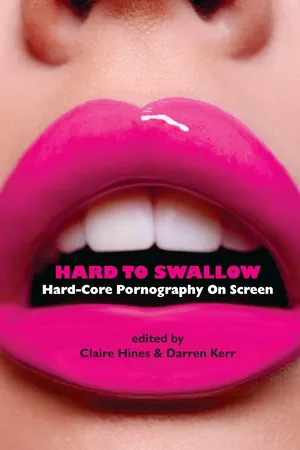

Even in our increasingly sexualized culture hard-core pornography and the representation of explicit sex is still hard to swallow. This lively and provocative new collection of essays by leading scholars explores screen representations of pornography and sex in a variety of cultural, historical, and critical contexts. Contributions cover a wide range of topics from sex in the multiplex to online alt-porn, from women in stag films to the excesses of extreme pornography, and a variety of contemporary case studies including porn performance, fashion in hard-core, and gay and lesbian pornography.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Hard to Swallow by Claire Hines, Darren Kerr in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médias et arts de la scène & Histoire et critique du cinéma. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

PORNOGRAPHY IN THE MULTIPLEX

Moving image pornography is as old as cinema itself. As has been the case with other media technologies before and since (print, photography, video tape, internet), the pornographic potential of film was an important factor driving its development – a killer application, indeed. Short pornographic films were being circulated in America in the 1910s and in France even earlier. Film made an enhanced voyeurism possible – watching others having sex, without the inconvenience of having to be present. In her discussion of the origins of moving image pornography Linda Williams (1990) links it to the ‘Animal Motion’ experiments of Eadweard Muybridge, and what she characterises as their fetishisation of the body. Pornography, she argues, takes fetishisation of the human form a stage further, for the purpose of sexual arousal, and in film finds an ideal carrier medium.

The illusion of reality permitted by the technology of the moving image was quickly spotted by early pornographers, and the first stag reels appeared in the late nineteenth century. The French ‘cinema of attractions’, ‘obsessed with exploring the mechanisms of looking made possible by the movies’, was visible in 1896 (Matlock 2004). These short films were made for exclusively male audiences, gathered together in brothels or at stag parties, at a time when female sexuality was suppressed or prohibited from free expression. The consumption of moving image pornography in early ‘cinemas’ is paradigmatic of the gendered nature of such consumption ever since. It began as a men-only pursuit, and if that male-ness has been diluted in recent years, porn has continued to be perceived – and critiqued – as an essentially male cultural form.

The content of the early stag reels was remarkably similar to that of later generations of pornographic movie – the graphic representation of sexual activity, unadorned by professional quality scripts, acting or production techniques; moving images of people fucking, in all the ways that were possible (and a few that were not, or only with great difficulty, but were tried anyway; The Good Old Naughty Days (2002), a compilation of French reels made in the 1920s, includes scenes of, as the Sight & Sound review puts it, ‘spanking, cunnilingus, fellatio, group sex, voyeurism, urination, masturbation, anal and vaginal intercourse, ejaculation and bestiality’ (Williams 2004)). To the extent that they had narratives, these were merely structuring devices for guiding the viewer from one climactic scene to another. The point of porn then, as now, was to turn the viewer on, to induce an erection, to bring him to the point of masturbatory orgasm by granting access to transgressive representations of otherwise hidden, private activities.

Because they were transgressive, early porn movies existed on the fringes of legality, if they were not outlawed entirely. Western societies policed porn with vigour in the early twentieth century, with grand gestures such as the throwing of 25 kilometres of ‘obscene’ film into the river Seine by the Parisian police in 1912. The desires porn stimulated were generally regarded as unseemly and shameful, their indulgence a private act of transgression, to be shared if at all only with other like-minded males. Like prostitution and gambling the consumption of pornography was not something one would wish to do in polite company, but was ritualised within male bonding contexts in which groups of men together had licence to look, whoop and holler.

Here again, the early history of moving image pornography is paradigmatic of what came later with the invention first of sound, then colour photography. Pornography was liberalised in the Western world in the 1960s, as is well known. But if it was no longer a criminal offence to view pornography in most countries (and rules about what could be shown in cinemas varied between, for example, the more liberalised regimes of Sweden and Germany, and the highly restricted environment of the UK), it remained a leisure activity steeped in shame. After the sexual revolution pornographic films were shown in cinemas for the first time, but only in specially designated ‘adult’ theatres, to audiences comprised largely of solitary men who sat and did what they had to do in the anonymity provided by darkness. Even after the sexual revolution the consumption of pornography remained a private, solitary practice, geared to masturbation, and not to the shared, public space of the mainstream cinema. If pornography was the pariah of representational practice, these X-rated venues were on the shadowy, shameful margins of cinema culture. They were legal, but hardly mainstream. In most cities they were located in the red light urban zones, often alongside sex shops, brothels and peep shows, removed from the sight of decent folk. Teenage boys, such as this author in the early 1970s, would sneak into places like the Classic Grand in Glasgow, to see porn films with titles such as Teenage Jailbait (1973), Erotic Dreams (1974) and Do You Believe in Swedish Sin?(1972) (see McNair 2002). The films were soft-core, reflecting the state of sexual censorship in the UK at that time, but the furtive nature of their consumption in these dark palaces of sin made them powerfully erotic.

For a brief period only can it be said that pornography became part of mainstream cinema culture, part of the popcorn and hotdog business. This was the first wave of porno-chic, taking in the early to late 1970s with films such as Deep Throat (1972) and Behind the Green Door (1972). The story of Deep Throat is well known, and features in a documentary made by Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato (Inside Deep Throat, 2005) and which was itself screened in cinemas as part of the trend towards porno-chic in the multiplex (see below). To summarise: the liberalisation and sexualisation of Western culture in the 1960s permitted pornography to become more explicit, more acceptable, and more ambitious in its aesthetic qualities. Films became longer, their scripts more developed, their production values more luxurious. They were still a long way from winning any awards (except those eventually established by the porn industry itself), but their makers aspired to artistic seriousness. P. T. Anderson’s Boogie Nights (1997) dramatises this phase of porn’s history, as we see Dirk Diggler (Mark Wahlberg) and his colleagues act out ‘proper’ narratives in which sexually explicit scenes are ‘contextualised’ by the action, rather than merely gratuitous. Boogie Nights pokes affectionate fun at the absurdity of this ambition, but it was sincerely held, and full-length feature films such as Deep Throat were the result. This 90-minute long film told the story of a woman who discovers that she has her clitoris in her throat. As a result, she can achieve orgasm only by ‘deep throating’ a succession of erect penises, a novel form of sex therapy which is shown in its full splendour.

Made for less than $200,000, Deep Throat appeared at a moment in US cultural history when sexual liberalisation had progressed sufficiently to permit exhibition in a mainstream cinema in New York. Ordinary people, as opposed to the raincoat-adorned brigade of sleazy perves who in the public imagination frequented adult cinemas, were curious about pornography, by then emerging into public view on a number of fronts. The stigma associated with the form was in decline, and anti-porn feminism was yet to unite with born-again evangelism to reinforce its pariah status. Thus, the queues which formed to see Deep Throat as the buzz around the movie spread included young and old, men and women, couples and grannies. For the first time, pornography crossed over from the underground of adult entertainment to that of mainstream cinema.

The huge success of the film at the box office encouraged similarly ambitious works, such as Behind the Green Door and The Devil in Miss Jones (1973) – sexually explicit, hard-core pornography (i.e. depicting penetrative sex), but framed with a degree of narrative sophistication and at least the aspiration to aesthetic worth. In less liberal regimes, such as the UK, this first wave of porno-chic produced less explicit soft-core films such as the Confessions… series, beginning in 1974 (see Hunt 1998). The same year also saw the first of the Emmanuelle films reach multiplex audiences, marketed not as pornography but high-class erotica for discerning liberals. Though less explicit, these films had the same significance in their respective markets as Deep Throat had in the US – they expressed the growing social acceptability of images which had previously been forbidden in public by legislation, or marginalised to the periphery of cinema culture.

This liberalism did not last. The rise of second-wave feminism in the 1970s brought with it an anti-porn discourse centred on the alleged contribution of the form to the maintenance of patriarchal culture. Moving image pornography, like advertising, was subsumed within the feminist critique of patriarchal culture’s general objectification of women. Its graphic representations of sexual activity were defined as oppressive, violatory, exploitative and degrading. As the women’s movement grew, the consumption of pornography became again a shameful activity, at least for those men who viewed feminism with empathy and solidarity.

As the 1970s gave way to the 1980s, the Reagan presidency saw a resurgence of born-again religious extremism in the US, and the emergence at the heights of government of another set of arguments against porn, this time premised on theological views of the sacred nature of human sexuality. Porn was demonic and sinful, in this reading, because it encouraged and championed sexual activity outside of the sanctified realm of marriage and family. In the mid-1980s anti-porn feminism fused with Christian evangelism, leading to the Minneapolis Ordinance and other gestures designed to criminalise or marginalise pornography (see McNair 1996). Pornography remained legal in the US, thanks largely to the protections on free expression and speech offered by the first amendment to the constitution, but it re-acquired pariah status, since viewing it branded one either as a sinner damned to eternal hellfire, or a misogynist only one step away from committing rape. The naive curiosity and excitement generated by the appearance of Deep Throat in 1972 was a thing of the past. As Linda Ruth Williams puts it in a review essay on Inside Deep Throat, ‘after a heady, anything-is-possible moment of “porno chic”, when the world and her husband queued up outside theatres and hard-core became the darling of the embryonic “couples audience”, came the shaky years when feminists joined hands with moral enforcers to censure the new form’ (2005b: 25).

The pornographication of mainstream Western culture (see McNair 2002) which occurred from the late 1980s brought a second wave of porno-chic, as we shall see below, and Deep Throat would later be revived, even canonised, in the re-evaluation of all things retro – including 1970s porn – which characterised the 1990s and 2000s. But pornography did not, and has not moved back into mainstream cinema, even momentarily, for one simple reason (I suggest). In the early 1970s and the era of Deep Throat, there was no video technology and no internet. Home computers did not exist. Moving image pornography could be viewed only on celluloid, either on home projectors or in cinemas. For most people, the latter was the most convenient means of accessing moving image porn.

In the 1980s and 1990s, as the production and consumption of pornography expanded in the liberal capitalist world, it did so not in the form of films made for cinema, but on video tape, disc, and then online, using personal computers. The consumption of pornography, to repeat, is an essentially private past time, indulged in as an accompaniment or prelude to masturbation. It is thus best suited to media platforms which allow solitude and privacy – the very opposite of cinematic exhibition. The dramatic expansion of what I have elsewhere called the pornosphere (McNair 2002) occurred, therefore, not in the cinema, but in the domestic environment, where it has remained. This is probably just as well, since pornography has never inspired what anyone could call great movies, even when accessing decent production budgets and artistic talent. Notwithstanding occasional attempts to demonstrate otherwise, pornography is stubbornly antithetical to art, whatever medium is employed to distribute it, and thus difficult to present in any context other than the immediate sexual self-gratification which has always been its distinctive aim. The challenge to make pornography which is at the same time aesthetically valid remains unfulfilled.

PORNO-CHIC IN THE MULTIPLEX

The expansion of pornography since the 1980s, then, has not occurred in the public sphere of the cinema, but in the private realm of the living room, on the back of technologies which decentralise, diversify and democratise the communication system, and which also make it much harder to control than ever before. Pornography has been globalised, through websites such as YouPorn. com which make what would once have been called ‘stag reels’ accessible to consumers all over the world, including countries in which traditional platforms for distributing porn, such as magazines and video tapes, were tightly policed. In the process porn has retained its transgressive essence, and thus its allure in markets where it was hitherto banned or restricted. Although it has never been more available, nor the legal and moral constraints on its consumption fewer, pornography remains a cultural form on the periphery of the mainstream. Why go to see porn in a cinema, when it can be accessed in the privacy of one’s own home?

There is a public, cinematic dimension to the expansion of pornography, however – part of the pornographication of mainstream culture which is at least as significant as the changing patterns of pornographic consumption permitted by new technologies. Pornography has become the subject of public discourse, as well as the object of transgressive desire, in all forms of popular media, from TV soap operas to style magazines and fashion (...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Dedication

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: Is Hard-core Hard to Swallow?

- Part 1. Turned On: Hard-core Screen Cultures

- Part 2. Come Again? Hard-core in History

- Part 3. Fluid Exchanges: Hard-core Forms and Aesthetics

- Selected filmography

- Index