![]()

ONE

DEFINITIONS

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SPIRALS (AND A WAY OF READING SPIRALLY)

It’s no calligraphy for school children. It needs to be studied closely.

• FRANZ KAFKA, “IN THE PENAL COLONY”

THE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE SPIRAL

Spirals are ubiquitous in nature, from plant and insect life, to human hair and fingerprints, to the movement of water and celestial bodies. Spirals have also, and increasingly, been used by corporations and in branding commodities. Innumerable products for children (films and television programs, toys, games) feature spiral shapes, and many companies have spiral logos. Perhaps this is because spirals express both the idea of growth and the pleasures of play. Give a young child a pencil and one of the first things he or she is likely to draw is a spiral. The infantile and youthful pleasures of the spiral, and its association with a kind of ur-writing, can certainly be viewed as in some way connected with its preponderance in twentieth-century literature and, especially, visual art. Yet my concern here is not with spirals as playful, ornamental decoration, or contrarily as universal “essence” in the mode of Corbusian architectural theory or Jungian psychoanalysis.1 Instead, I proceed from the premise that spirals in twentieth-century literature and art express in their very forms a relationship both to history (which is to say, political-economic history) and to novelty and conceptions of the new. To begin to flesh out this approach, it is imperative to recognize that spirals themselves have a history and to demonstrate how they incorporate that history.

In a short essay on the work of visual artist Bernard Réquichot, which was first published in 1973 and later appeared, in English translation, in the collection The Responsibility of Forms, Roland Barthes juxtaposes the contours of the spiral with those of the circle. “The circle,” he writes, “is religious, theological; the spiral, like a circle distended to infinity, is dialectical: on the spiral, things recur, but at another level: there is a return in difference, not repetition in identity. Thanks to [the spiral], we are not constrained to believe: everything has been said, or: nothing has been said, but rather: nothing is first yet everything is new.”2

Barthes’s subtly emphatic observations provide a productive framework through which to begin to explore more closely the image of the spiral in literature and visual art in the twentieth century. More particularly, they offer a way to conceive the relation of different spirals in literature and visual art to one another across that century. Indeed, Barthes both asserts the inherent historicity of spirals and challenges notions of historical continuity. While his description of “dialectics” is by no means identical with that of Walter Benjamin, explored briefly in the introduction, the possibility that “nothing is first yet everything is new” bears an important resemblance to Benjamin’s conception of emergence, for which Benjamin draws on a spiral figuration, as we will shortly see. Moreover, Barthes’s notion of the spiral as a “distended” or, better, “deported” circle—Barthes calls it “un cercle déporté à l’infini”—is not only a claim about the relation of the emergent to what-has-been, but a demonstration, on the level of the sentence, of a “profane” spiral effect whose properties this book will pursue.3

But before proceeding with an account of this formal profanation, it behooves us to wind back toward the word itself, to seek its definition. The noun “spiral,” according to the OED, is a term from geometry describing a “continuous curve traced by a point moving round a fixed point … while steadily increasing (or diminishing) its distance from this” fixed point. As with many familiar forms—take the classic example of a line—geometry gauges the relation between a fixed or an original point and a point or points in the distance. Unlike many other familiar geometrical forms, however, of crucial importance in and for the spiral is the movement that connects those points. The spiral curves or swerves around in such a way as to produce what Barthes calls “levels” of distance from or proximity to the fixed point.

And yet, the OED’s definition not only fixes the meaning of the spiral, but, with its unusual parenthetical reversal of direction, reveals an important ambivalence inherent in the geometric form itself, one that confounds attempts to establish origin and distance-from-origin. Does the spiral travel outward from the fixed point, thereby increasing its distance from that point, or curve inward, diminishing that distance? To cite Paul de Man citing All in the Family’s Archie Bunker: “What’s the difference?”4 In the former case, the fixed point could be conceived as a kind of center, but one unlike that of a circle, since its circumference stays open. In the latter, the inward, “diminishing” direction implies that the fixed point or origin is in a sense on the outer edge of the structure. Opening or closing, dissipating or concentrating: as we shall see, this ambivalence or bidirectionality inherent to the spiral form is crucial both for the twentieth-century visual artists and writers who embrace the spiral as fundamental to their practice and for a study that seeks to understand or take account of the art and literature involving or revolving around those spirals.

The OED’s examples of the usage of “spiral” offer a glimpse of the word’s complicated and fascinating history. According to the dictionary, the modern English noun “spiral” was first deployed by Thomas Hobbes in 1656, in his translation of his own Elementa Philosophica, and then again by John Dryden in 1697, in his translation of Virgil’s Georgics, describing the motion of the sun. Not surprisingly, then, the word comes to English via the French and Italian spirale from the late medieval Latin spiralis, an adjective that the German scientist, philosopher, and theologian Albertus Magnus is noted by the OED to have used, in passing, in 1255 when describing the coiling movement of the celestial sphere (notions for which he is said to be indebted to the medieval Andalusian philosophers Averroës and al-Bitruji).5 The Latin spiralis is thus cognate with the Greek σπεĩρα (speira), an everyday word describing anything wound, coiled, or wrapped around.

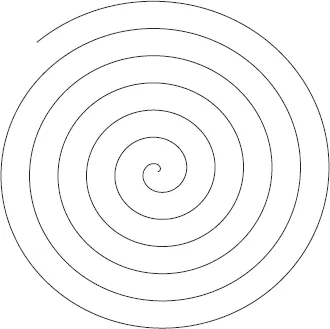

In the classical period, the spiral form was a source of fascination from early on. As Barthes seems to be ventriloquizing, Plato, in Timaeus, speculates that there are three fundamental movements of the universe: circular, for the stellar gods; rectilinear, for brute matter; and spiral, for “planetary souls.”6 Accordingly, the earliest geometers, including Euclid, took note of the form, prevalent among planetary dwellers, and made some rudimentary calculations. Yet among the ancient Greeks, the spiral is most closely associated with Archimedes of Syracuse (ca. 287–212 B.C.E.), in whose honor the most familiar representation of the form was eventually named (figure 1).

In a long letter to his fellow geometer Dositheus, thought to have been written around 222 B.C.E., Archimedes set forth twenty-eight increasingly complicated propositions, starting with Euclid’s calculations, extending them into a study of the way the form “turns” first once around a center and then turns again, and showing how each of those turns (τρόποι [tropoi]) can be measured. (The detailed mathematics of this measurement will not concern us here, but it is worth noting that Archimedes frequently repeats that he seeks to gauge what he calls the “forward” movement of these spiral turns, by which he presumably means “outward.”) The understanding of these “tropes” was no abstract exercise for Archimedes, who was not only a geometer but also what today would be called an engineer; it was of enormous practical importance in the Hellenistic period, explaining, for example, the way screws and drills function, and in so doing advancing the science of architecture and the refinement of construction techniques.

Archimedes’s letter, along with the manuscript of other work in which it was included, is thought to have been translated into Latin sometime before the late fifteenth century.7 But that translation, like many Greco-Roman translations, is itself not untendentious: in the Greek original, the text was untitled, but in manuscript editions the chapter accrued the name Περὶ ἑλίκων (Peri helikon; On [or About] the Helices), and in fact Archimedes consistently used the noun helix and not the adjective speira. When the text was given the Latin title De lineis spiralibus (On Spiral Lines), Archimedes’s discussion of a three-dimensional form (the helix) was in effect, at least titularly, condensed or flattened into a two-dimensional image associated with a “line.”8

1 Archimedean spiral. (Image courtesy of Marc Edwards)

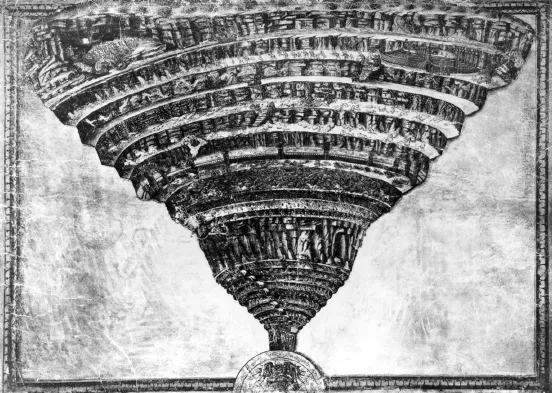

And yet, despite the condensation that takes place in the translation from Greek helix to Latin spiralis, in the late Middle Ages the spiral form preserved a sense of its helical depth and extensity, drawing on its association in the classical period with the movement of the celestial spheres and of the soul’s wandering (Plato) and with zoological ideas about natural life, as in Virgil’s Georgics or indeed in Lucretius, who, in De rerum natura, uses the term clinamen to describe the “swerving” movement of atoms.9 Consider, for example, Dante’s Divine Comedy, as famously illustrated by Sandro Botticelli, in which the directionalities of the pilgrim’s wanderings—which is to say, the architectonics of hell and purgatory—are, respectively, downward and upward spirals; the pilgrim moves, as the Dante scholar John Freccero convincingly demonstrates, a sinistra, descending into the funnel of hell, and a destra, ascending the Mount of Purgatory (figure 2). These points of reference can make sense, or be cognitively mapped, only when considered in relation to Dante’s broader cosmological world picture, which Freccero argues necessarily involves both spatial and temporal dimensions: “Just as we use a clock in our post-Copernican world for spatial reference when we use the words ‘clockwise’ and ‘counter-clockwise’ as well as for measuring time, so celestial movement gives the pilgrim his time references in the poem, and also provides him with a means of telling … [his] direction.”10

2 Sandro Botticelli (1444–1510), “Map of Hell,” ca. 1480, in Dante, The Divine Comedy. (The Art Archive at Art Resource, New York)

If, in the late Middle Ages in Europe, the soul was conceived as capable of either descending to a sinister eternal hell or rightly ascending to an eternal heaven via a “time-filled” spiral journey, it is of little surprise that the form is so frequently found in the architecture of Romanesque and Gothic churches. Consider, for example, the cathedrals of Notre Dame and Chartres and Mont Saint-Michel, with their prevalent narrow spiral staircases and heavenward-pointing spires, not to mention the spiral-like forms in their stained-glass windows; these allegorical forms are as didactic, and sometimes as complicated, as Dante’s. (Returning for a moment to the word: curiously, the etymology of the architectural “spire” bears no relation to that of “spiral”; neither does “spirit” or the Latin verb spirare [to breathe], though as we shall see these ideas are often viewed as cognate.)

In early modernity, the spiral’s late medieval associations with religious aspiration—and indeed, desperation—began to be translated into the dual idioms of scientific utility and aestheticized beauty. In Leonardo da Vinci’s illustrations for the Divina Proportione, in the architecture (attributed to him) of the Château de Chambord, and especially in his 1493 sketch of his proto-helicopter (a helix that depends on a conical spiral), huma...