![]()

1. EZRA POUND AS NOH STUDENT

[A] celestial maiden of the moon-laurel tree…present here briefly: for so the world learned the East Country’s Suruga Dance!

Royall Tyler, Japanese Nō Dramas

HAGOROMO (THE FEATHER MANTLE) IS ONE OF THE MOST POPULAR and frequently performed plays in the noh repertory and often the first studied by amateur students like myself.1 An angel (tennin) from the palace of the moon teaches a sacred dance to a fisherman after he steals and returns the feather garment that allows her to fly home. The unknown author of the play draws partly from the myth of a dance lesson given by a “heavenly maiden,” which Zeami references as a divine influence on the development of noh.2 Ezra Pound and W. B. Yeats studied Hagoromo, or an impression of the play, in 1914 with Itō Michio and several of the Japanese dancer’s friends. Itō, who had not trained in noh performance technique (not even as an amateur), staged the first version of Hagoromo in the United States in 1923. He used the English translation first published in 1914 by Ezra Pound, who had not studied Japanese. Yeats then relied on Itō and Hagoromo when he developed his own bird-maiden for At the Hawk’s Well (1916), the first and most influential of his dance plays modeled on noh. Judgmental accounts of the network claim that Yeats appropriated the noh form from Pound’s error-ridden translations and Itō’s unreliable teachings. Hagoromo opens with the theft of a sacred object and ends with a dance class that also teaches humility, a lesson that might apply to the difficulty of differentiating cultural robbery from collaborative teaching and learning.

Pound, Yeats, and even Itō certainly misunderstood aspects of noh and exhibited orientalist assumptions about the East as spiritual, traditional, mysterious, and essentially different from the West. But this might be the least interesting thing to say about a collaboration and series of lessons that influenced some of the most fascinating artworks of the twentieth century. Pound’s so-called “mis”-representations and “mis”-translations point to the errors and creativity that are present in any translation. Cultural exchange always provokes uncertainties about who should be authorized to represent or teach a culture, why and how students should learn it, and even if there is a “real” or “true” culture that can be taught.3 My goal here is not to “correct” the errors that I consider inevitable; to do so would imply that I claim the authority to represent a “true” Japan and knowledge of some “essence of noh,” a claim that would fall into the orientalist trap of imagined, essential differences between the East and West. In the spirit of the fisherman who learns noh from a moon angel, I engage Pound’s modernist noh collaborations with a focus on the pedagogical practices, desires, and erotics that shape the transmission of any cultural form. Like all performance genres, noh is a learned technique, and a focus on pedagogy is particularly appropriate to the emphasis on training in the noh tradition, the didactic elements in plays like Hagoromo, and the lessons that disseminated noh in modernism.

In this chapter, I use the play Hagoromo to introduce noh drama and its Buddhist-inflected ideas of personhood or subjectivity that are not defined by oppositions between subversion and submission. Noh’s representations of subjectivity influenced Pound’s construction of a multilayered or (what he might have called) “ideogrammic” poetic speaker as well as his rejection of common Western and liberal definitions of the person. Pound’s putative failures as a noh student and teacher had a generative function that is evident in his performances, theories of imagism, and The Pisan Cantos (1948). Composed when he was imprisoned by the U.S. military for treason and controversially awarded the Bollingen Prize while he was incarcerated at St. Elizabeths Hospital (formerly the Government Hospital for the Insane), The Pisan Cantos presents anti-Semitic and pro-fascist ideas along with many ghosts from noh plays and the collaborators who helped him translate them. Although Pound was not the only modernist artist to use foreign art to promote distasteful politics and bigotry, he did so more loudly than many others. Considering Pound as a translator, collaborator, and noh student provides a different foundation from which to read the controversial works that exerted such a profound influence on modernism and still have much to teach us about the atrocities of the twentieth century.

THE LESSONS OF HAGOROMO

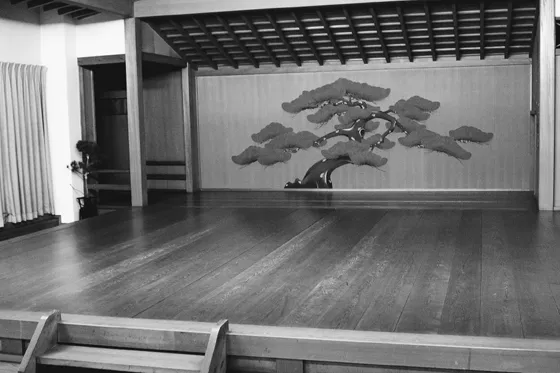

At the opening of Hagoromo, stage assistants place a small pine tree with a robe in its branches at center stage to suggest the setting at Miho Bay’s pine groves (Miho no matsubara). The only scenery for noh plays are stage properties called tsukurimono (literally, “built things”), like this pine or the bare frame of a boat, usually made of bamboo wrapped in white cloth with little effort to make it look like a real thing (figure 1.1). A large pine tree called the oi matsu (old pine) is painted on the back wall of the theater as, according to Fenollosa, “a congratulatory symbol of unchanging green and strength” (PFNoh, 36). The stage is constructed of polished Japanese cypress to form a square with pillars (hashira) at the four corners (figure 1.2).4 A bridgeway (hashigakari) extends approximately twenty-five feet from stage right and is flanked by three pine trees of decreasing size to create an impression of distance (figure 1.3). The orchestra (hayashi) includes a shoulder drum (kotsuzumi), hip drum (ōtsuzumi), flute (nōkan), and, in Hagoromo and slightly more than half of the 250 other plays in the noh repertory, a stick drum (taiko).5 Stage assistants (koken) kneel in seiza behind the musicians at the back of the stage, and eight to ten performers in the chorus (jiutai) kneel stage left.

With the stage set, the waki (witness character) and several companions (wakizure) enter down the hashigakari. They sing of the fishermen at Mio in a verse pattern (shōdan) known as issei, an ornate section sung in a rhythm that does not match the beat of the drums.6 In most plays, the shite soloist chants the issei, and by disrupting this convention, Hagoromo presents the waki as exceptional. He introduces himself in the second section, a naming verse (nanori), as “a fisherman named Hakuryō” (JND, 101). Hakuryō means “White Dragon” and refers to a Chinese story about a dragon that left heaven, turned himself into a fish, and was injured by a fisherman (JND, 99). The King of Heaven refused to condemn the fisherman because humans are permitted to kill fish. The author of Hagoromo, reading the Chinese myth as would an early modern Buddhist, uses Hakuryō to invoke the multilayered nature of humanity and the accretion of reincarnated lives. Hakuryō contains within himself the injured dragon, fallen from divinity and reborn through karma as the object of his hatred, as well as a human fisherman at risk of descending farther into hell.

FIGURE 1.1 A tsukurimono (built thing): the frame of a boat bound to the wall. (Courtesy of David Surtasky)

FIGURE 1.2 A noh stage. (Courtesy of David Surtasky)

FIGURE 1.3 The hashigakari (bridgeway) leading to the noh stage. (Courtesy of David Surtasky)

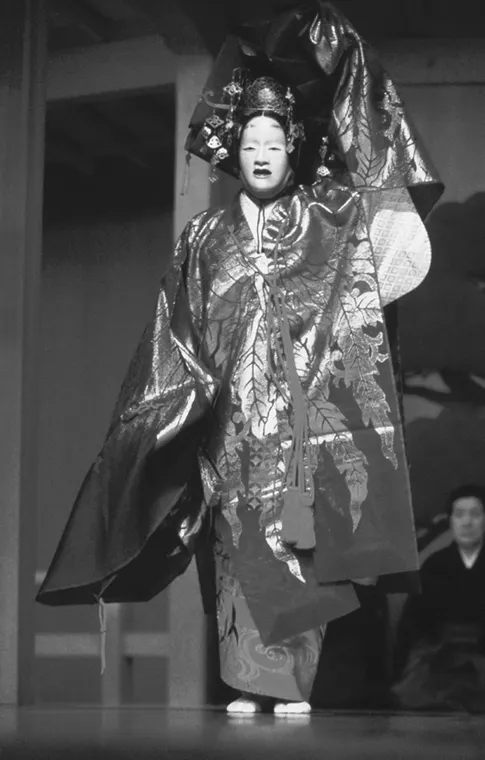

Hakuryō’s encounter with the feather mantle is a test, and his failure would result in his further fall from enlightenment. Early in the play, he celebrates in poetic language the pleasures of spring, indicating that it is possible for him to be uplifted by a “beauty to transport the heart with keen delight!” (JND, 101). The “wave washes the shore” and the “moon / loiters in the plains of Heaven,” lines that bring together distinct, even oppositional substances (water, moon, and earth) and suggest that they could merge like the dragon and fisherman (JND, 101). As the waki, Hakuryō’s function is to enable and witness the appearance of the shite, the tennin (angel) from the palace of the moon. He takes the feather mantle from the pine, and the angel calls out in protest from offstage.7 The angel walks slowly down the bridgeway in the suriashi (sliding-foot walk) dressed in a sumptuous costume, elaborate headdress, and, usually, the zō-onna mask for young women and divinities (figure 1.4).

Hakuryō initially refuses to return the mantle, for high-minded familial and nationalistic reasons; he will “show it to the elders” and “make it a treasure of the realm” (JND, 102). Several other passages celebrate Japan’s emperors as “gods’ offspring” who “still rule / the moon-illumined land, source of the sun” (JND, 106). The play also quotes from a poem that was adapted for the modern Japanese national anthem, a passage suggesting the nation will endure for as long as it takes an angel’s mantle to wear away the rock it brushes. These references to Japan’s longevity as a sacred nation made Hagoromo an obvious choice for performance at the coronation of the Taishō emperor in 1915.8 The play sets earthly values, politics, and beauty next to the heavenly, asking, “Heaven and earth, why, are they not one?” (JND, 105). If they were, the angel would not need her feathered mantle to return to her home on the moon. The play suggests that oppositional, divisive thought is one source of the separation. Hakuryō’s challenge is to find the divine dragon within his fallen human state, not by an assertion of power, but through a deep sympathy that closes the gap between self and other, fisherman and tennin, waves and shore.

Hakuryō’s lesson in sympathy begins as the angel pleads with him to return the robe in language that is emotionally elevated by a shift from prose to poetry (mondō to kakeai).9 Hakuryō acknowledges his own unkindness, just as the angel laments “her desperate plight” (JND, 103). The connection between the characters is emphasized when Hakuryō takes lines that might have been sung by the angel or a narrator:

ANGEL: What then shall I do? in distress she cries,

HAKURYŌ: and when Hakuryō still withholds the mantle,

ANGEL: helpless,

HAKURYŌ: hopeless. (JND, 103)

FIGURE 1.4 Hagoromo: “It is as if the whole dance lives in the sleeves of the feather robe, performing the way of the Palace of the Moon.” (Photograph © Toshiro Morita, provided by website http://www.the-noh.com)

The chorus (jiutai) breaks in at this moment to describe the “five signs of an angel’s decline” that signal her approaching death (JND, 103). The noh chorus sometimes chants lines that represent the speech of the shite or waki and sometimes describes the stage action as would a narrator, a variation that seems to break down the distinctions between characters.

Noh language in English translation feels not only poetic but also “unrealistic,” in part because Japanese pronouns do not specify subjects. The translator faces difficult choices with pronouns because English speakers rarely refer to themselves in the third person, and Hakuryō’s reference to himself by name is not particularly unusual in Japanese but is unusual in English. Other unrealistic features in noh performance include the chant-like vocal delivery, masks, ornate and bulky costumes, slow suriashi walk, forward-leaning posture (kamae), musicians, chorus, and stage attendants, that is, nearly every aspect of noh performance. Pound and other modernists appreciated these features as part of noh’s demand for “acting that is not mimetic” (PFNoh, 5). Noh is not mimetic in that it does not imitate Western ideas of “reality” or comply with the conventions of Euro-American realist performance, even though convention is precisely what makes an acting style seem like a realistic representation of life. Euro-American audiences expect actors to ignore their presence in a the...