![]()

1

BUDDHISM AND THE PSYCHEDELIC CONNECTION

IN 1996, the popular Buddhist magazine Tricycle: The Buddhist Re- view published a special edition devoted to the topic of Buddhism and psychedelics.1 It included the results of a poll of readers titled, “Psychedelics: Help or Hindrance?”2 The findings from the 1,454 responses (63% from the magazine and 37% from the web) were summarized as follows:

89% said they were engaged in Buddhist practice.

83% said that they had taken psychedelics.

Over 40% said that their interest in Buddhism was sparked by psychedelics, with percentages considerably higher for boomers than for twentysomethings.

24% said that they were currently taking psychedelics, with the highest percentages for people over 50 and under 30.

41% said that psychedelics and Buddhism do not mix

or 59% said that psychedelics and Buddhism do mix.

The age group that expressed the most confidence that they do mix was under 20.

71% believe that “psychedelics are not a path, but they can provide a glimpse of the reality to which Buddhist practice points.”

58% said they would consider taking psychedelics in a sacred context. (In the “under 20” category, it was 90%.)

Rather striking in this data is the high percentage of those who have taken psychedelics (83%). Also worth noting is the age grouping: the older baby boomers and younger “twentysomethings” and “under 20” group seem to be more involved, interested, and confident in the religious/sacred use of psychedelics. These figures appear to support the editor, Allan Badiner’s, claim that (at least in the mid-nineties) “psychedelic use is on the rise again.”3 I will revisit this issue below. For now, let us look at some more of the data that have been collected.

In his study of Western Buddhists,4 James Coleman found similarly high percentages of psychedelic drug use among the membership of seven different Buddhist centers in North America:

Over 62% of Western Buddhists he surveyed said that they had used psychedelics;

Of those, half said their use of psychedelics played some role in attracting them to Buddhism;

5 and

80% of Western practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism said that they had used psychedelics.

6These figures are in stark contrast to the estimated 8% of the U.S. population thought to have experimented with psychedelic drugs, based on government surveys.7

Charles Tart, in his survey of members of the Rigpa Fellowship,8 an organization led by the Tibetan Nyingma lama Sogyal Rinpoche, found that among the 64 respondents:

77% reported previous experience with a major psychedelic, and of those:

49% had 1–10 experiences,

18% had 11–50 experiences, and

10% had 50 or more experiences.

Tart also found that “90% of the respondents report that they no longer use major psychedelics, 10% that they use them at least once per year but less than once per month. 19% indicate they expect to use major psychedelics in the future and 32% that they might.”9 Tart’s data seem to show that for members of this organization, psychedelic use largely dropped off as they became more involved in traditional Buddhist practice.

My online survey (conducted July 19, 2010, to July 26, 2011) had the following results from 196 respondents:

85.1% considered themselves Buddhist.

61.6% had tried LSD at least once.

33.3% continued to use psychedelic substances.

61.4% of those who continued to use psychedelics said their use of these substances was for spiritual/religious purposes.

49.3% said that Buddhism and psychoactive substance use are compatible.

Here I need to make an important caveat: these surveys are not from random samples; nor are the sample sizes large. They give no indication of how widespread the spiritual use of psychedelics might be within American Buddhism. At best, they offer some anecdotal evidence concerning this heterodox and often outlawed practice among American convert Buddhists. However, the surveys do suggest some correlation between the practice of convert Buddhism and the use of psychedelics, and demonstrate that at least some American Buddhists not only have tried psychedelics but also continue to use them. In the Tricycle survey, respondents were largely from the regular readership of the magazine, and it is probable that those with some previous psychedelic drug experience were more likely to express their opinions on the matter. Likewise, Coleman’s survey was a “purposive sample” of two Zen groups (Berkeley and Rochester Zen Centers), two Tibetan groups (Karma Dzong in Boulder, Colorado, and Dzogchen Foundation in Boston, Massachusetts), two Vipassanā groups from the San Francisco Bay area (one led by Gils Fronsdal and other by James Baraz), and one nonaffiliated Buddhist group (the Heron Sangha of San Luis Obispo, California).10 As mentioned, Tart’s survey was from a single Tibetan organization, the Rigpa Fellowship.

My survey, which I attempted to give a neutral title—“Attitudes Toward Psychoactive Substances Among American Buddhists”—was compiled through the SurveyMonkey website. To promote the survey, I e-mailed both individuals and Buddhist organizations in the United States, sending a URL link to the survey, and asked them to pass it on to anyone they thought might be interested. I also developed a Squidoo website providing information on and a link to the survey, and asked people to post the link online.11 My sampling was “purposive” or “selective,” rather than random. The primary goal was to acquire qualitative data concerning a cohort of American Buddhists who use or have used psychedelics and to understand their views on the relationships they see between the practice of Buddhism and the use of psychedelics. I was particularly interested in uncovering the views of “psychedelic Buddhists,” people whose practice of Buddhism is augmented or supplemented with the use of (a) psychoactive substance(s) for spiritual/religious purposes. Additionally, I contacted various contributors to the Tricycle edition on Buddhism and psychedelics and Zig Zag Zen, and asked if they would like to complete the survey and/or be interviewed. I also asked that they forward my e-mail to anyone whom they thought might be interested in the survey or in being interviewed. Most (but not all) of my interviews were conducted with people who completed the survey.

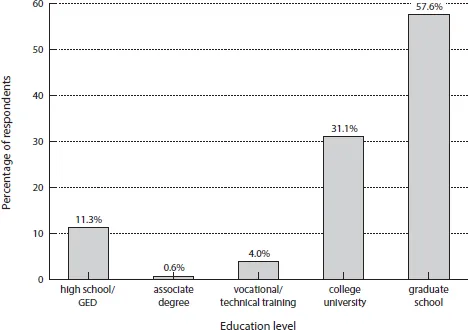

Significantly, most of the survey responses were obtained shortly after I e-mailed the link to the academic H-Buddhism list of scholars. Thus the results of my survey may over-represent what Charles Prebish calls “A Silent Sangha in America”—academics studying Buddhism who also have a personal interest in the religion.12 Further evidence of this possibility is provided by the 177 who answered the question, “What is your highest level of education?”: 57.6% had attended graduate school.

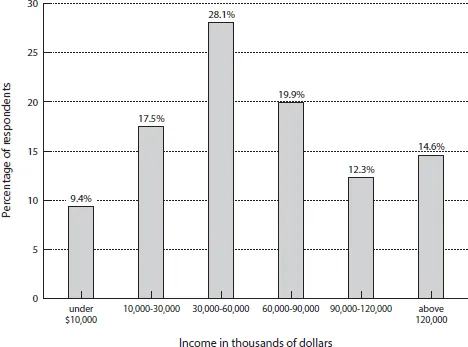

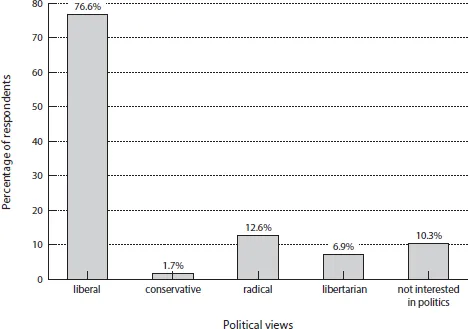

What other demographic data do we have on American convert Buddhists? Coleman’s survey of Buddhist groups found that 58% of the respondents were female and 42% were male.13 The sample was overwhelmingly Caucasian/white (about 90%), and those of Catholic or Jewish background were over-represented compared to national averages. While the age range was from 19 to 78, the mean age was 46. Coleman also found that most of those surveyed were from the middle and upper-middle classes, were far more educated than average Americans, and were more politically liberal. The results from my survey largely corroborate Coleman’s findings. The age range of respondents was 18 to 74, with a mean age of 42. Over 95% of the respondents indicated that they were “Caucasian” or “white.” Like Coleman’s sample, respondents tended to be middle to upper-middle class, highly educated, and politically liberal (see figures 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3). However, unlike Coleman’s results, male respondents outnumbered females in a ratio of 65% to 35%. As some of Coleman’s data suggest, this may indicate a stronger interest in psychedelics among male convert Buddhists than female converts.14

FIGURE 1.1 What is your total gross family income per year?

FIGURE 1.2 What is your highest level of education?

FIGURE 1.3 How would you describe your political views?

There are a number of possible reasons for this gendered aspect of psychedelic Buddhism. One is that the use of psychedelics (especially potent substances in high doses) may appeal more to males than females, in the same manner that extreme sports and dangerous occupations such as law enforcement, the military, and firefighting generally appeal more to men than women. Another reason might be that males are simply more vocal about their interest in and use of psychedelics than females (and there is no substantial gendered divide in interest or use). Sarah Shortall has pointed out the lack of counterculture discourse on “the way gender mediated and differentiated the drug experience,” and how writing on drug exploration in the 1950s and 1960s rarely portrayed women in an active role.15 A number of publications in recent decades have begun to recover some of women’s experiences in the counterculture, and I recommend these to the interested reader.16 In an online survey about gender and sexuality in the psychedelic community (148 respondents; 96 male), Joseph Gelfer found that:

When asked if they felt there was equality within the community, 61 percent of people answered positively. Most stated that the community was more welcoming to diversity than mainstream society. However, a vocal minority felt the community was “a bit of a boy’s club” and women were “often sidelined as just ‘the girlfriends.’” A difference emerges here between the opinions of men and women, inasmuch as women were more likely to identify inequality.17

Gelfer’s results appear to support the results from my survey and interviews. Again, this may mean that white, middle-class men are more interested in psychedelics than white, middle-class women, or that men are more likely to share their experiences. Finally, a possibility that cannot be discounted is researcher bias. As a white male convert to Buddhism, I may have gained a greater rapport with male participants during interviews, and I was able to network better with and solicit more information from men than women. Because my sample size was limited, there is no way of knowing with any degree of certainty if males are in fact more highly represented than females among psychedelic Buddhists. However, given my data, men seem to be more interested in mixing Buddhism and psychedelics, and therefore I have focused more attention on men’s religious narratives. There is no valuation here of men’s stories above women’s.

...