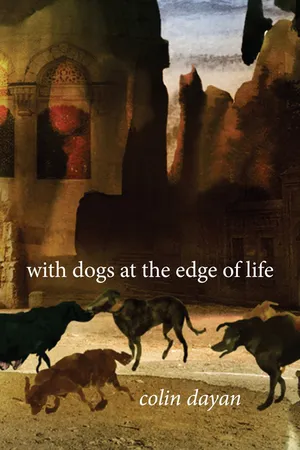

![]()

part one

like a dog

![]()

MY LIFE, WHAT I REMEMBER of my childhood, began with a dream. I dreamed that I was in a dump, out there in the dirt with broken footstools, cracked dishes, and piles of toys. No one else was there. I had been dropped off and left alone right before the sun set. I do not remember myself—how I looked, what I felt. All I see even now are things. The things in the dirt are not garbage, not like the stuff you throw in trashcans. They are weighty, extravagant, and intemperate in their height and clutter. That is the feeling I have when I call up the dream. I am there thrown away in a heap, in the midst of junk that, treasured once, still seems effervescent with love, imprudent in excess.

What are the things that get left behind, disposed of, forgotten? In heaps they pile up, one on top of the other, a clutter of dead bodies that somehow hold on to life: in the limb thrown softly onto the back of its neighbor, in the mouths held open, not quite ready to turn away from the life they knew. This held breath, the hot blood and flesh of abandoned stuff, matters to those who live. To know our easy disregard is to hold fast to the sight of what we push aside. Only then do we come to know what we have lost. In the piles of the dead, things still hold the pulse and beauty of what we claim to cherish but continue to kill.

Dogs are captive in the yoke of care and cruelty that defines our status as humans. They are property and persons, both res nullius, or no one’s thing, and valuable possession. Our contradictions, inconstancy, and greed continue to make large groups of persons, whether human or nonhuman, expendable. And nowhere is that indignity as clear as in our relationship with dogs. Nowhere do we experience so fully the alternating closeness and disregard of those who master—those whose rituals of disposal undergird and sustain the soft, closeted lives of the privileged.

It is with the dogs that I begin. They are the things of great attachment that can be cast off. Their relentless passion and full heart compel a new understanding of spirit and a new appreciation of flesh. Though blessed, they are also like the junk I dreamed about and into which I was tossed. This book is about what gets treated as refuse, tossed off as trash in the world of high-status human animals. But it is also about the dogs that, in spite of the constant uncertainty of their lives, saved me from the dump, calling me back, again and again, to life.

![]()

chapter one

dogs and light

Deep the woods and dark the scent

As the bright season lengthens

Into the work of the mind for

Which the dogs live

VICKI HEARNE, “NEWS FROM THE DOGS”

A PHILOSOPHER, POET, and professional trainer of horses and dogs, Vicki Hearne died on August 21, 2002. Her husband, Robert Tragesser, sent me the notes to the preface of the posthumously published “Tricks of the Light,” the five-part sequence poem that she worked on right up until her death. It was published in the volume of collected poems with the same title. She felt the need to explain her change of muse from horses to dogs:

But I have outlived and outwritten the ability to invoke exalted horses who outlive or outwrite the ability to send a good or, if the gods should so will a great, dog out into the fields of the imagination, and its forests, its planets.

It is not that no preparation is needed. I have put the supernatural, that is to say, great, dog in the place of the winged horse, and the good dog in the place of the serviceable word.1

Her words return dogs to their rightful place as medium of thought and criterion of utterance. Their thought is heavy and palpable as flesh. The sure sign of the spirit, as Saint Paul knew, could be touched, held, and smelled. In “Tricks of the Light” she speaks to and with the dogs. She lets her readers know the stirring of knowledge that is none other than the dog’s personal surpassing:

the dog’s leap beyond herself

and a twirl and flash

of a toothed belief.2

I first met Vicki at Yale. Into the office across from me she brought two pit bulls, Michael and Annie, and two pink plastic chaise lounges. It was the first time I ever saw dogs like them, so intense, focused, and muscular. Vicki’s office mate, a non-dog-loving medievalist, did not welcome them. But who ever expected pit bulls in Linsly-Chittenden Hall? Walking up the stairs with Vicki and her dogs seemed to me a glorious ritual, one of great concentration. I remember feeling as if light shone around their bodies, and I was honored to accompany her and the dogs. Even now I sense the demands of her belief, and I hear her airy gasp that meant a dog was in sight. I held the dumbbell, the choke collar, and the long line, heavy and magical in my hand.

Years later, when I had moved out to the Tucson Mountains in Arizona, Vicki came to visit. By then I had the three dogs of my life: Dogie the Rottweiler, Mehdi the Am Staff, and Jesse the black Labrador. Dogie, the oldest and the largest of the three, never took to training. His trainer became my lover. That probably contributed to his recalcitrance. Or maybe I was just too lax and easygoing. Vicki took Dogie out to the front steps of the house in Tucson. It was hot, it was summer, and she had accepted my love and his bad training. My dog sat, and she put choke collar and long line around his neck. He would not move. There he sat, at the top of the steps. So dragged he was, down the stairs, all 120 pounds, and then he landed flat out on the ground, with Vicki, who joined him there, laughing.

Vicki had no truck with smug oversimplifications or pious surmises based on narrow judgments about victimization and mastery. Claims of humane treatment are not reassuring. Dogs can be killed with kindness. Nothing is more dangerous to their sense of themselves than coddling. The choke collar, used correctly just once, with the impersonality of a force of nature, gives a dog the space in which to focus, to know where and how it wants to be. The annoying sound of the clicker, on the other hand, crowds the dog into acknowledging what it might want to ignore. So one click usually will not do. The bribery of treats follows. This coaxing requires no intimacy between dog and person, no exchange of recognition. Ignored as capable of intent or will, the dog must accept the characterization that remains: nothing more than a creature with an insatiable appetite. So we have Elizabeth Costello’s story of Sultan the ape in J. M. Coetzee’s The Lives of Animals: “At every turn Sultan is driven to think the less interesting thought. From the purity of speculation (Why do men behave like this?) he is relentlessly propelled toward lower, practical, instrumental reason (How does one use this to get that?) and thus toward acceptance of himself as primarily an organism with an appetite that needs to be satisfied.”3

In Bandit: Dossier of a Dangerous Dog, her remarkable story of saving a dog sentenced to death, Vicki describes what happens when people give positive reinforcement, such as biscuits, to teach dogs to sit. Such rewards reduce “the complex of meanings” that a dog can give to the act of sitting. “Continual treat reinforcement of the puppy’s sitting discourages the puppy from trying to mean anything but a treat…. Truth becomes a dog biscuit, an M&M, a sitcom, or cocaine…whether or not the human beings know that in the process they and the dog have lost a language and thus a world.”4

I remember Vicki’s visit to the University of Arizona in 1994, where her words and presence struck terror in the hearts of many dog-loving professors in the audience. She urged that the character and responsibility earned through absolute obedience to the craft of training give dogs both a language and a presence squarely in the world. My colleagues complained: “Her use of force is fascist.” One woman boasted, “I use a clicker to show my dog who is boss.” That evening at a cocktail party, Vicki, who dared take out a cigarette, was told to go outside. Ignored by everyone, there she stood for the next few hours, alone, in the desert on a terrace under the stars. She had been banished, I thought. Vicki had stamped in hunger for the word, sweated to the cadence of reflection, and beaten out thought in brutal prose. The promise of language and the rapture of thought held always tight in the leap, the retrieval, the tracking of dogs. So she writes of dog knowledge, learning at the edges of work in “Tricks of the Light”:

Proof is all in the mind,

the mind is all in the world,

the world is a star

caught in a young bitch’s teeth

just as she is learning the grab

of the heart that sends her past hurt

into her work, leaving doubt

in the dust of regret

that stains the bureaucrat’s breath.5

In our decent and all-too-human times, Peter Singer argues for the sanctity of animal life by making an analogy between animals and the incapacitated and insane. Since animals suffer and feel pain like these disabled humans but have the added ingredient of reason, even if limited, they deserve to occupy a place of rights as “non-human persons.”6 The horror of drug testing on dogs and cats, of the care and stuffing of cows or chickens, pigs or sheep, for slaughter is not debatable. But Singer’s argument comes close to the ethical pathos of abolitionists arguing for the better treatment, even emancipation, of slaves, granting freed slaves—as Frederick Douglass knew—some utility, even understanding, but never respect, not the privilege of possessing their own thought or speaking to their own people.

Singer counters reasonableness against degrees of incapacity—capable of more or less reason—as a necessary bulwark against cruelty. What, then, do these rights so urgently invoked look like, and legally, how would they be constituted? In arguing against Singer, Hearne used to talk about his indifference to consciousness, memory, and judgment—the personal identity—of animals. As she never tired of saying, humanitarian claims reduced dogs to objects of charity, or worse, to servile recipients of their masters’ beneficence. Easy certainty undermines what matters most in the mutuality of adaptation between humans and dogs.

The greatest dog I ever had was the worst dog, or so I thought at the beginning. Mehdi hated and feared men, especially arrogant, tall ones. He bit them. He attacked a rather macho dog trainer one day in the backyard of my house in Tucson. I found him wandering around Oak Creek Canyon in Sedona, Arizona. He looked like a deer. Abandoned, he had fleas in his ears and ate only leaves and insects. I tried to teach him to eat meat or sit for dog biscuits, but he always preferred lettuce and anything green. He was an American Staffordshire terrier. Mehdi was also a good judge of character. He went for the balls of particularly pompous men. When I injured my back not long after I found him, he became more aggressive. He went after a colleague who came to visit me. Another colleague, and, yes, another male who was well meaning and caring, explained that sometimes euthanasia is the only answer. After all, he explained, he and his former wife had a dog that ate shoes. They could not get him to stop. So they killed him. For this professor there was no such thing as training. Only coaxing was allowed. Discipline held no appeal for him. It was too cruel.

Vicki lay dying in a hospice in Connecticut. After she died, I drove from Tucson, my home of ten years, to the East Coast. I decided to search for Red River, the site of John Wayne’s film of cows and honor. Once past Fort Stockton, Bakersfield, and Ozona, I realized I had not found it. On the way to San Antonio, I stopped for the night. Getting out of the car with my dogs, I knew that this first night outside Tucson marked the end of a kind of peace, the sun and sky that left humans in awe of things not often remarked on or known: the precise grasp of a Harris’s hawk; the summer dance of the tarantulas; the wolf spider pulsing in the corner of a room; the wail of the Colorado River toads after August monsoons; footprints left in the dirt by the nighttime wandering of the javelina; long-backed lizards pressed against the windows; and coyotes searching for kill as bulldozers devoured the Sonoran Desert.

Let the elegy begin. The turn to things lost, the end of much that I loved. In the humid summer of Philadelphia, I understood the meaning of that thing I saw in Sonora, outside of San Antonio. After feeding Dogie, Mehdi, and Jesse, I went out to the car to get my bags. I saw something stuck to the front grill of my car. A bird on the grill. In the night wind, the thing that once had been a sparrow must have flown toward the headlights. Trying to get it off, using a pencil and then a large comb, I saw that its guts were stuck, wrapped into the steel. Stuck by its guts. A curse, I thought. The next day, as I drove through sun into heavy rain, I prayed that it would fall to the ground. Instead, the sparrow held on all the way to Philadelphia. Once there, when I parked the car across the street from my new house, the bird finally dropped off. Dried out in the heat, it fell to the ground, hollowed out and folded like a dead leaf.

The life it asks of us is a dog’s life.

JAMES MERRILL, “THE VICTOR DOG”

BECAUSE YOU LOOK AROUND and find them looking at you. Then you become yourself to yourself. You exist. Your home has meaning. But that is not exactly it. It is not about me, but about flesh shot through wit...