![]()

Part 1

Early Film Combustion

![]()

1

Early Cinema and the Comedy of Female Catastrophe

FIGURE 1.1 Frame enlargement from Mary Jane’s Mishap (G.A. Smith, 1903)

Scenarios of women spontaneously combusting while doing housework offered irresistible subjects for early film representation. Mary Jane’s Mishap (G.A. Smith, 1903) provides an especially iconic example that, unlike many slapstick comedienne films, is still extant today. In this short comedy, a British housemaid accidentally blows herself to smithereens and erupts out of the chimney while attempting to light a hearth fire with paraffin. Mary Jane, played by the filmmaker’s wife Laura Bayley (one of several comically gifted Bayley sisters),1 then rains down in dismembered body parts over the village skyline, and finally returns to haunt her own gravestone as a dancing specter.

Mary Jane’s Mishap enacts a more elaborate adaptation of the Irish housemaid comedy The Finish of Bridget McKeen (Edison, 1901), which itself was a two-shot remake of the single-shot film How Bridget Made the Fire (Biograph, 1900).2 In these latter two films, the famous female impersonator Gilbert Saroni plays an untidy maid who accidentally incinerates herself in the process of attempting to expedite her housework with kerosene. (Mary Jane’s poison is paraffin wax.3) Meanwhile, an Irish domestic is electrocuted by a battery-wired turkey in A Shocking Incident (Biograph, 1903), and a flirtatious Irish maid falls victim to an exploding bowl of flour when her employers’ son plays with fireworks in Nora’s 4th of July (Biograph, 1901).

In these comedies of female catastrophe, the mundane routines of conventional domesticity and the dangerous effects of modern housekeeping technologies become innovative sources of exuberant fun and visceral surprise. But why were self-immolation and other forms of gendered domestic violence causes for joyous laughter rather than horror or pathos? This chapter focuses on the conspiratorial relationships between comical laughter, gender and sexual violence, and modern upheaval in early short-form filmmaking. Early films reveled in their very representability of movement: what would be cause for alarm or danger in real life (such as combustion, dismemberment, and assault) was a hilarious sight gag once projected on-screen. Due to its abrupt temporality of violence and minimal focus on the aftermath, early cinema parlayed corporeal apocalypse into visual curiosities, provoking extravagant laughter from weary spectators. By cutting apart the film strip and eliding interim images of the body, decapitation could appear bloodless, combustion quick and harmless, and sexual violence a mere opportunity for mischievous fun and tricky role reversals.

The gender politics of how these cinematically dissected bodies became laughable bear further feminist analysis and historical contextualization. Female accident was a frequent hazard of modern industrial life in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As I will describe, women caught fire in their homes in deadly “crinoline conflagrations,” exposed their bodies to sexual predation in public spaces, exhausted their labor in grueling domestic work, suffered deplorable conditions in dangerous sweatshops, and tested the limits of their too-tight corsets against the physical upheavals of riding on streetcars or visiting amusement parks and fairgrounds. These incidents of female catastrophe were all too mundane in the modern public sphere’s gender-integrated spaces. Though not quite as spectacular as spontaneously combusting out of the chimney, many of these horrific accidents were reported in a derisive or jocular tone. Instead of lamenting the modern hazards of traditional feminine accoutrements (corsets, enormous hoop skirts, oversized bonnets), commenters mocked women for the incongruity of their feminine fashion juxtaposed with their volatile, technologized urban environments. The specters of traditional femininity were thus laughed off as ridiculous sight gags: modern horrors made fun through recourse to demeaning stereotypes of feminine rigidity.

Comedy philosophers have encapsulated the comic spirit as the lithe body reduced to rigid absurdity. This is Henri Bergson’s still widely cited definition of comedy: “something mechanical encrusted on the living.” Debates about laughter, modernity, and mechanization have tended toward universalist abstraction, invoking the mechanical body of comic laughter as largely androgynous. Critiques of Bergson focus on his instrumentality (his notion of laughter as a mere tool for disciplining wayward bodies), and his problematic argument that laughter allows no space for emotional empathy. Yet what this abstract universalism further disallows is nuanced attention to the slippery gender and sexual politics of comic mechanization. When women’s bodies become funny in these early catastrophe comedies, it is always due to the recognition of something abruptly left behind: perhaps just a limb or a head, or perhaps something much deeper and more confusing to identify.

Catastrophe, from the Greek katastrophem, meaning “overturning” or “sudden turn,” always has the potential to become comical: like catastrophe, comedy hinges on surprise, spontaneity, and punctual shock. More than just smoke screens for anxieties about women’s bodily infiltration of the public sphere, early comedienne catastrophe films become funnier the more they encroach on reenacting the very disasters that they purport to defer. In other words, laughter and terror provide mutual enablers for spectators to embrace the underlying instabilities of historical change. Women’s mangled, dismembered, and incinerated bodies were among the principal protagonists in this endless cycle of looming catastrophe and uproarious release.

In these films, women reimagine their own femininity through promiscuous object and bodily attachments that always erupt in spectacles of gleeful destruction. As we have seen, a deadly paraffin bottle allows a bored housemaid to catapult herself into the public sphere in Mary Jane’s Mishap, while the ingestion of nitrous oxide gives a black woman immunity to police brutality and juridical punishment in Laughing Gas (Edison, 1907). After visiting her dentist, Mandy Brown (Bertha Regustus) spreads her laughter contagiously and indiscriminately to the police force, as well as to the white working-class, some gospel revelers, and a justice of the peace. In Madame’s Cravings (1906), one of over seven hundred films directed by Alice Guy-Blaché, Guy plays a pregnant woman who exhibits her maternity cravings in public. The sight gag of her voracious appetite (as she devours a child’s lollipop, pickled herring, smoking pipe, and glass of absinthe) climaxes not with ingestion but with excretion, in the exhibitionist scene of her trick childbirth, rendered here by a spontaneous jump cut. The film is comical not because Guy plays a fool (though her husband is a bit of a sad sap), but because the terms of domestic femininity and its shape-shifting place in the polis are subject to continuous reinvention and corporeal mutation.

Similarly, in comedies about sexual assault (of which there were too many to enumerate), women ward off predators by dissolving into billboard posters (as in Kiss Me!), acquire facial hair through trick cuts (A Sticky Woman, Gaumont, 1906), or partake in cross-racial masquerades through plays on dark lighting (What Happened in the Tunnel, Edison, 1903). The comic sight gag, often at the masher’s expense, was less about the “rigidity” of the male predator’s temporary emasculation than about the comic potentials of how these volatile, novel technologies could revolutionize the gendered social order. Mary Jane might lose her head (though she gets it back in the end), but the spectator will never forget the jolting impact of its sudden loss, even if the eruption of surprise quickly dissolves into laughter. Georges Bataille’s critique of Bergson is useful here. Bataille argues that laughter at automatic gestures is never wholly intentional or “corrective,” but profoundly revealing and potently transformative. Though by no means a feminist, Bataille placed his laughter on the side of risky unknowing: the nonknowledge that runs roughshod over masculine enlightenment rationality. It is precisely this instance of unknowing—of unleashing deeply desired but impractical possibilities through volatile upheavals of the body—that comedies of female catastrophe flaunted and celebrated. From emigrant Irish housemaids to migrant African American women and pregnant female consumers, comical visions of women undergoing simultaneously physical and social transformations haunted the silent screen.

Crinoline Conflagrations and the Everyday Mishaps of Female Combustion

The comedy of female catastrophe finds its source materials in the everyday dangers of female embodiment. The characters Mary Jane and Bridget McKeen were not spun out of whole cloth: “first as tragedy, then as farce,”4 the exploding maids of early cinema evoked recent and contemporary histories of women catching fire while doing housework. Crinoline, a stiff fabric made from horsehair and cotton, was widely used to enlarge the skirts of women’s petticoats and dresses. Although fashionable and conventional, these bulky, starchy dresses and bloated hoop skirts easily caught fire while women were attempting to heat their homes or cook meals for their families.

Derisively referred to as “crinoline conflagrations,” such incidents were subjects of journalistic fascination throughout the nineteenth century. An 1858 article titled “The Perils of Crinoline” published in the New York Times reflects the impulse to transform these modern calamities into gendered objects of comic ridicule:5

Almost every fact in human life, we are told, has its serious and its comic sides, and each deserves attention. Of the availabilities of crinoline, considered comically, perhaps enough has now been made…. But the crinoline question has graver aspects, which are forced upon us afresh by accounts today of the frightful death in Boston, on Friday night last, of a young lady… who was standing near the chimney-piece when her garments suddenly took fire, and before the requisite pressure could be brought to bear upon them, were entirely consumed, inflicting injuries so many and so severe that she survived but a few hours.

To varying degrees, the intermingling of comedy, horror, and pathos was endemic to the discourse of crinoline conflagrations. First, the fashion of crinoline was viciously mocked. One writer lamented the “ridiculous nuisance” of crinoline: “There is no possible or probable situation or circumstance in which a woman can be placed in which its inconvenience and absurdity is not palpable—walking, riding, or dancing; in rail car, omnibus, church concert or theater… or any imaginable or supposable household duty.”6 Notwithstanding the fact that crinoline fashion was primarily dictated by male designers and dressmakers, it was widely decried as the folly of women for adorning themselves in such unwieldy fabric. Bergson should have said “something crinoline encrusted on the living.” To this point, the accidents or mishaps provoked by the awkward garb could be innocuously amusing, such as a woman knocking over a table rather than catching fire. The comicality of crinoline thus gains momentum from its simultaneous visible excess and unpredictable consequences. Like a jack-in-the-box, one knows it will go off, but is ever surprised and delighted when it manages to do so—unless its eruption becomes fatal.

Second, the pervasive ridicule of crinoline provided an emotional alibi for its sad reality and tragic repercussions. Did women truly relish wearing crinoline? Victorian novelist Charlotte Perkins Gilman suggests not, in her essay on the redemptive potentials of film montage:

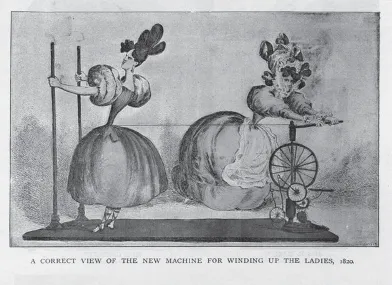

If the last sixty years were shown in all their changes of women’s dress on the same figure, swelling and shrinking, rising and sinking, trailing on the ground, cut off to the knee, wasp-waist and no waist, high collar and naked back; if the thing were presented as a whole, with its increased change of speed, then we might be able to stretch our minds wide enough to ask why we must thus spin like a top under the lash of a salesman.

Gilman’s critique of female fashion trends, which in aggregate stretch women’s bodies to more astonishing extremes than the editing of an early trick film, reveals the social stakes of laughter at feminine absurdity (see also figure 1.2). In conservative definitions of comedy such as Bergson’s, it is always the external object of ridicule (outmoded fashion, a facial tic, absentminded behavior) that prevents comic outbursts from escalating into something uncontainable. The absurdity of crinoline, as a metonymic token of feminine excess and frivolous desire, is emphasized to provide mental relief from the messy contradictions between the vestiges (or at least vestments) of traditional gender norms and the contingent dangers of up-to-date domesticity. Laughter momentarily contains the unresolvable conflicts that will eat away at social traditions—either progressively through reformist organization or violently through civic strife and revolutionary upheaval.

FIGURE 1.2 “A Correct View of the New Machine for Winding Up Ladies, 1820.” Art and Picture Collection, New York Public Library

Evidently, the comedy of female catastrophe was viewed as all too mundane. The Times article reports that an average of three deaths per week occurred from “crinolines in conflagration,” which “ought to startle the most thoughtless of the privileged sex; and to ma...