![]()

MONSTER FROM THE CRETACEOUS LAGOON

THE SAHARA, EGYPT

In 1911, a Bavarian palaeontologist found a partial skeleton in the Sahara Desert of a very peculiar carnivore, even bigger than T. rex, and with a huge sail on its back – but a wartime bombing raid blew the fossils to pieces, and the creature seemed forever lost until an unlikely chance encounter in Morocco in 2013.

Crabs scuttle along a tidal flat near the entrance to a great braided river system that is flowing out to sea on the north coast of Africa, 95 million years ago. Apart from the insistent buzz of insects, all seems quiet along the banks, as animals rest in the shade to escape the heat of the midday sun. A crocodile the length of a bus is sleeping, its tail poking out from vegetation. But things are not as tranquil below the surface of the wide, slow-moving river channel. A fizz of bubbles hints at the presence of giant, car-sized coelacanths and lungfish lazily moving through the waters. Nearby, a more energetic giant sawfish is waggling its several-metre-long rostrum, lined with barbed teeth, through bottom sediments as it hunts for prey.

None of these fish has noticed what is stealthily gliding towards them below the water with a flick of its great tail. Made obvious above the water by a great red sail, which slices through the surface, this killer moves almost silently and invisibly through the murky waters. It is an enormous carnivorous theropod, but it has very unusual adaptations for a dinosaur – including flattened, possibly webbed feet, a barrel-shaped body, and pits along its snout where pressure sensors detect movement in the water. The only semi-aquatic dinosaur we know of, it mostly preyed upon the giant fish that lived alongside it in these Gondwanan river systems, and rarely on other dinosaurs

Our first hints of this enigmatic creature came from Ernst Freiherr Stromer von Reichenbach, a Bavarian aristocrat who undertook a series of fossil-hunting expeditions into the Egyptian Sahara between 1901 and 1911. His fossil collector, Richard Markgraf, found tantalising clues to a massive carnivore – a creature even larger than T. rex – which Stromer named Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. It had features he was at a loss to explain, such as a 2-metre-tall sail and a long, almost crocodilian jaw packed with conical teeth.

Stromer studied the fossil back at his Munich museum, but many of the pieces were missing, leaving gaps in his knowledge. All hopes of learning more were dashed during World War II, when an Allied bombing raid in 1944 destroyed the museum and most of Stromer’s Egyptian fossil trove, including all of the bones of Spinosaurus. All that remained were publications, field notes and a few sepia photographs. The book seemed to have closed on Spinosaurus.

But then in 2013, a young Moroccan–German palaeontologist, based at the University of Chicago in the United States, made a fortuitous discovery thousands of kilometres west across the Sahara from Stromer’s original finds. His find was so strange and so compelling it made the cover of National Geographic magazine.

A series of lucky breaks

Nizar Ibrahim is sitting outside a cafe in the eastern Moroccan city of Erfoud in March 2013. There’s a buzz in the evening air as locals head out to shop at the souk or gossip over mint tea, and tourists come back from the Erg Chebbi Dunes. Part of the reason for Ibrahim’s trip out here this time, to the Moroccan Sahara near the border with Algeria, is that he’s hoping to spot a fossil hunter he’d met here previously – a man who may be the key to uncovering important details about a very significant specimen. But Ibrahim, then aged 31, knows it’s a long shot. He ran into the guy once before, in 2008, and aside from a somewhat fuzzy recollection of his face, all he can remember is that he has a moustache.

The story really began in April 2008, when a young Ibrahim was first in this oasis town after several weeks prospecting for fossils amid the stark beauty of the desert. ‘We were collecting some really incredible fossils’, he tells me. ‘Thousands of specimens – remains of crocodile-like hunters and flying pterosaurs, and also dinosaur teeth and bone fragments. We found bits and pieces of Spinosaurus, but really nothing that would dramatically improve our understanding.’

He was resting in town after the dig when a fossil hunter brought him a cardboard box full of pieces that were clearly from a large animal but covered in sediment and thus difficult to make out. But one unusual piece caught Ibrahim’s eye – a section of dense, flat, blade-shaped bone. He thought it could be part of a massive rib – and, in passing, even wondered if this is what a broken Spinosaurus sail spine might look like look. Turning it around in his hands, Ibrahim noticed a red streak running down the middle of the cross-section.

Then in the midst of his PhD research, he decided to leave the mystery bones with his colleague, Professor Samir Zouhri at the Université Hassan II in Casablanca, but hoped he would one day return to study them. ‘It was always on my mind, and I often thought it would be nice if I could identify these bones.’

In 2009, Ibrahim found himself at the Civic Museum of Natural History in Milan, Italy. His colleagues there, Drs Cristiano Dal Sasso and Simone Maganuco, showed him the partial skeleton of an odd dinosaur in the basement, which had been donated by an Italian fossil dealer in North Africa. They wanted to return it to its country of origin, but couldn’t be sure it was Moroccan.

‘They showed me the bones and my jaw just dropped, because I saw that this was a part of carnivorous dinosaur, which in itself is rare…But also it had leg bones, strange claws and an almost complete foot. The claws were flat, which is very unusual in predatory dinosaurs, and the feet looked almost flat and paddle-like’, he says. ‘And there were ribs, backbones, tailbones, hipbones, pieces of the skull.’

Excited, his pulse racing, Ibrahim tried to piece the information together. But when his eyes rested upon what were obviously several long sail spines broken into pieces, he knew what this had to be. Then he looked at the spine in cross-section and saw a red line. ‘I thought, wow, this looks familiar’, he says. Not only did Ibrahim have a good idea this was Spinosaurus from Morocco, but the size, shape, colour, texture and sediment around the bone – as well as the telling red streak – hinted this was the same individual animal the moustachioed fossil hunter had brought him pieces of several years earlier in Erfoud. His mind whirring, Ibrahim pondered whether the guy had kept digging the same site, turning up more bones, which had found their way to Milan.

This would be a miraculous coincidence – it would mean he could confirm the first skeleton of Spinosaurus from Morocco, but also potentially return to the same spot to look for more of the individual, and then collect the all-important contextual information that would tell him the age and all the details of the environment the species had lived in. ‘But to do that I had to travel back to Morocco and relocate the man’, Ibrahim says. ‘Now that’s where our problems started.’

He hadn’t entirely told the truth to the Moroccan colleagues he was travelling with in March 2013, including Samir Zouhri, as he knew it sounded ridiculous. Eventually he admitted his plan, but was embarrassed to confess that all he could remember was that the man had a moustache. ‘Many men of a certain age in this part of Morocco have a moustache’, he says. ‘It really didn’t narrow things down, and – to paraphrase what my colleague said, because he was not very impressed – that was a very poor starting point for our search.’

Nevertheless, they went to the border region and stopped at spots where they knew people were digging precarious tunnels hundreds of metres into the rock to find fossils. They chatted with locals, but couldn’t find anything helpful, and were fast running out of time. Ibrahim had all but given up hope, and on the last evening was sitting in a pretty dejected state outside the cafe in Erfoud, sipping mint tea with Zouhri and also Dr Dave Martill, a palaeontologist from the University of Portsmouth in the United Kingdom.

‘I was at my lowest point’, Ibrahim says, ‘and then I just see this person walking past our table and there was just something – like a déjà vu moment – and all my senses were on high alert. And the man had a moustache, of course, and I just thought, “This is the guy”. It was so odd, I thought I was hallucinating’.

Never one to let an opportunity pass him by, Ibrahim stood up and darted after the man. A brief conversation in Arabic revealed it was the mystery man. He remembered Ibrahim and said that he had indeed found more bones at the site and sold them to an Italian dealer. ‘Everything suddenly fell into place. It was just an incredible moment.’

The man remembered for what he’d lost

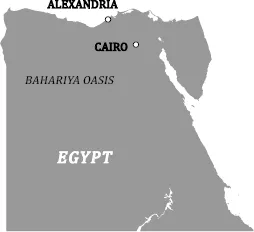

A little over a century earlier, in January 1911, German fossil hunter Ernst Stromer had also struck gold in North Africa – but this time in Egypt, almost on the opposite side of the continent. Though Egypt was then part of the British Empire, Germans had played an important role in the European exploration and mapping of its Western Desert. Stromer was following in that tradition when he had first visited Egypt in 1901, to explore the El Fayoum region, south-west of Cairo, which is rich with mammal fossils from the Eocene–Oligocene boundary, about 34 million years ago. Egypt was a fertile ground for finding fossils – Baron Nopcsa of Transylvania (see chapter 3) had visited the Fayoum Oasis in the years before World War I, and corresponded with Stromer on a number of occasions.

On his second visit, Stromer arrived in Alexandria in late 1910, and from there planned an expedition via camel train to the Bahariya Oasis, 290 kilometres south-west of Cairo. Stromer made many of his discoveries with the help of his Egypt-based fossil collector and friend Markgraf. Although Markgraf missed this particular expedition through illness, he returned to Bahariya in the years that followed and collected many of Stromer’s important finds.1 Stromer had a specific objective – he was setting out to find fossils that would back up his notion that mammals originated in Africa – and we know a great deal about his expedition because his journals still exist. ‘He recorded his activities in fastidious – one might say numbing – detail’, says author William Nothdurft, who gives an English account of Stromer’s adventure in his book The Lost Dinosaurs of Egypt. ‘Each journal entry is dated, his location given in precise coordinates, the times noted to the minute.’

On 18 January 1911, after many days of largely fruitless searching in the area between the Fayoum and Bahariya oases, Stromer struck gold at the north-western corner of Bahariya at a spot called Gebel el Dist. But it wasn’t at all what he was looking for: he’d found a dinosaur graveyard, and in just a few hours turned up a thighbone, vertebrae, part of a rib and ‘a gigantic claw’. With what Nothdurft describes as characteristic understatement, Stromer scribbled: ‘Apparently these are the first of Egypt’s dinosaurs and I have before me the layer that contains land animals’.

But he had no idea how to ‘conserve such gigantic pieces…or transport them to Fayoum’. Having come to find small mammals, Stromer lacked the tools or means to excavate them and transport them back to Munich via Cairo. Eventually, with the help of Markgraf, the array of dinosaur fossils was packed into eight crates and shipped to Munich – and Stromer arranged for Markgraf to return to Bahariya, to continue the prospecting and excavations.

After the onset of World War I in 1914, it became impossible for Stromer to ship many of his remaining fossils to Munich. With the help of Swiss palaeontologist Bernhard Peyer, he finally managed to get hold of them in 1922, but they arrived damaged and broken into hundreds of pieces.

Between 1911 and 1914, Stromer and Markgraf had found the remains of three giant carnivorous dinosaurs – Bahariasaurus, Carcharodontosaurus2 and Spinosaurus – and one herbivorous sauropod, which Stromer called Aegyptosaurus. They also found small pieces of another sauropod and some carnivores that were more difficult to identify, as well as snakes, crocodiles, turtles and marine reptiles. Spinosaurus itself was described in a paper in 1915, but Stromer continued to describe the material until 1936 – it became his life’s work.

Like Spinosaurus, Carcharodontosaurus was also probably bigger than T. rex. And following a 2007 study from researchers at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Canada (inventively titled ‘My theropod is bigger than yours…or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods’),3 it held the title of largest carnivorous dinosaur of all – until the discovery of the new, much more complete Spinosaurus specimen in 2013. According to the estimates in the 2007 study, published by François Therrien and Donald Henderson, Carcharodontosaurus would have reached 13.26 metres long and around 15.1 tonnes, while T. rex only stretched to 11.97 metres and 9.11 tonnes.

Carcharodontosaurus was a predator that looked similar to Allosaurus or T. rex, but was possibly heftier and meaner. Perhaps T. rex’s enduring place as the ‘tyrant king’ of the dinosaurs in most people’s minds has to with the fact it is a prominent species from the United States – and that more than 50 specimens have been found, many largely complete. Though Stromer’s Carcharodontosaurus specimen was one of the ones later destroyed, the University of Chicago’s Paul Sereno found another skull in Morocco’s Kem Kem fossil beds in 1995 – and then later a further specimen in Niger, which was described as a new species, C. iguidensis, rather than the original C. saharicus.

But the sum total of remains is still paltry compared to the impressive selection of T. rex skeletons on display around the world. It is interesting to note that Henry Fairfield Osborn’s description of T. rex in 1905 achieved massive fame globally, but Stromer’s descriptions of Spinosaurus in 1915 and Carcharodontosaurus in 1931 sank almost without trace. In 1915 at least, with the advent of World War I, people had other things on their minds.

The fact that two of the largest carnivorous dinosaurs ever known lived near each other in the same region is interesting, too – could they have both grown so large because they sometimes faced off against each other in battles for territory around the water’s edge? Or was there another factor at play here in this North African region of Gondwana? At this stage nobody knows for sure.

Bahariasaurus was another allosaur relative, in a similar size range to T. rex. Unfortu...