![]()

1

THE BATTLE OF KOSOVO OF 1389 AND SERBIAN NATIONALISM

In his defense of the notion of collective memory, the Israeli philosopher Avishai Margalit includes an interesting discussion of why the Battle of Kosovo still carries such emotional power for the Serbs, whereas the Battle of Hastings is all but forgotten by the English.1 This is a good question, and answering it suggests something about the range of possible ways in which people in the present day may relate to past events. Both battles, after all, signaled vital turning points in the histories of their respective countries. How is it that the alleged defeat of the Serbs at the hands of the Ottoman Turks in the Battle of Kosovo continues to be so deeply and passionately felt more than six centuries after its occurrence, but the French defeat of the English at Hastings has been relegated to the history books?

THE KOSOVO MYTH

The first thing we learn when we look into this question more carefully—and it is telling—is that in fact very little is known about what actually happened in the Battle of Kosovo. There is a widely held view among historians today that an earlier Ottoman defeat of the Serbian army in 1371—an encounter that took place in the Maritsa (Marica) River valley in what is now Bulgaria and resulted in the slaughter of large numbers of Serbs—was of far greater consequence militarily, permitting the Turks to extend their control over southern Serbia and Macedonia. By 1389, the Serbs were plagued by low morale and disunity, with numerous noblemen alternately fighting against and forming alliances with one another. When the Ottomans threatened, Lazar Hrebeljanović, a noble who had extended his territorial control after the battle of 1371 and become one of the more powerful Serb leaders (he is often referred to as “Prince Lazar” owing to a title conferred on him years earlier), chose not to submit. The battle that resulted was fought on June 28, 1389, on Kosovo Polje (Field of Blackbirds), a few kilometers distance from Priština. Both Lazar, who headed the Serbian force, and the Ottoman Turk leader Sultan Murad were killed. The battle itself, although remembered by the Serbs ever since as a calamitous Serbian defeat, seems in fact to have been somewhat inconclusive. Indeed, it was not until 1459, some seventy years later, that Serbia finally succumbed to the Turks.2

How, then, did the Battle of Kosovo become, in the words of one Serbian scholar, “the central event” in the entire history of the Serbian people?3 Two factors were of key importance. One was the emergence in the years immediately following the battle of a flurry of epic poems and folk ballads that dealt in heavily mythologized fashion with the fall of the Serbian state and the inception of a condition of vassalship under the Ottomans, an alien society with an alien religion. The other consisted in the Serbian Orthodox Church’s energetic promotion of a Christianized reading of what had transpired. The two together, focusing on a number of prominent participants and substantive themes, produced in embryonic form the myth or legend of Kosovo.

The core of the myth, which reached its culminating shape in the nineteenth century, was the “Kosovo covenant,” according to which Lazar was said to have been invested with Christ-like characteristics already on the eve of the Battle of Kosovo. Presented with the choice between a kingdom in heaven or a kingdom on earth, he opted for the former, exclaiming that “it is better for us to die by a heroic act than to live in shame.” The Serbian scholar Olga Zirojević elaborates: “Lazar’s words are accepted by his warriors[,] who reply in the form of a chorus; the idea of death is elevated to a heroic feat through which they will pass to eternal life. Through their sacrifice, the Serbs earned freedom … in the heavenly kingdom, … out of the reach of any conqueror. Although defeated, they were never enslaved.”4 Soon after the battle, Lazar was canonized by the church. The cult of the dead leader was preserved in ten cycles of folk ballads created between 1390 and 1419. His bones were also preserved and, as late as 1988, were carried in a religious procession from one holy site to another in Serbia before being deposited, in time for the six hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo, in the great Gračanica monastery adjacent to the plain where the battle was fought.5

A major theme of the Kosovo legend is the tension between loyalty and betrayal, as represented primarily in the figures of Miloš Obilić (or Kobilić) and Vuk Branković. This tension reflected the historical reality that after the devastating defeat of 1371, which accelerated the collapse of the great medieval Serbian Empire built by Stefan Dusan (who reigned as king from 1331 to 1346 and as emperor from 1346 until his death in 1355), numbers of Serbian warriors did in fact go over to the Ottoman side,6 some of them, in dramatic subversion of what the legend tells us, very probably fighting alongside the Turks in the Battle of Kosovo.7 A key episode in many renderings of the Lazar story is the dinner the prince gives on the eve of the battle. In one version—the version first set down in writing and published in the nineteenth century by Vuk Karadžić—Lazar drinks a toast to his knights. When he gets to Miloš Obilić, he refers to him as a “faithful traitor”: “first faithful, then a traitor! At Kosovo tomorrow you will desert me, you will run to Murad, the Emperor.” In anger, Obilić jumps to his feet to defend himself and identify the real traitor:

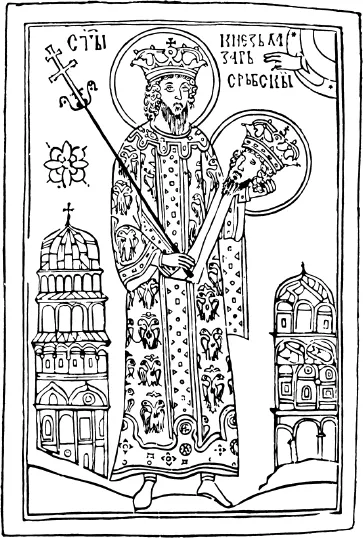

FIGURE 1.1 Prince Lazar, late seventeenth-century image, in the Museum of the Serbian Orthodox Church, Belgrade. (From Thomas A. Emmert, Serbian Golgotha: Kosovo, 1389, East European Monographs no. 278 [New York: Columbia University Press, 1990]. By permission of Thomas A. Emmert.)

I have never been any traitor,

never shall be one,

at Kosovo tomorrow I intend

to die for the Christian faith.

The traitor is sitting at your knee

drinking cold wine under your skirts:

Vuk Branković, I curse him.

Tomorrow is lovely St Vitus day

and we shall see in Kosovo field

who is faithful, who is the traitor.

The great God is my witness!

Tomorrow I shall march on Kosovo,

and I shall stab Murad, Tsar of Turkey,

and stand up with his throat under my foot.

And if God grants and my luck grants

that I shall come home to Krushevats*

I shall take hold of Vuk Branković,

and I shall tie him on my battle-lance

like a woman’s raw wool on a distaff,

and carry him to Kosovo field.8

FIGURE 1.2 Fresco of Miloš Obilić, with the halo of a saint. Serbian Monastery of Hilendar on Mount Athos, first decade of nineteenth century. (From Thomas A. Emmert, Serbian Golgotha: Kosovo, 1389, East European Monographs, no. 278 [New York: Columbia University Press, 1990]. By permission of Thomas A. Emmert.)

Luck, according to the legend, did not grant Obilić’s wish. On the pretext that he wanted to join the Turkish side, he is said to have entered Murad’s tent and killed him with a dagger that he had concealed under his clothing, after which he himself was promptly slain. This act proved beyond any doubt Obilić’s heroism and loyalty to Lazar and the Serbian cause, and the real traitor, Vuk Branković, became “the ancestral curse of all Slavic Muslims.”9 Although scholars have questioned whether the historical Branković actually betrayed the Serbian side and whether Obilić even existed historically,10 the metaphoric power of these two individuals in Serbian national consciousness was (and remains to this day) immense, Branković being represented as the archetypical “negative character, a slanderer, defiler and traitor,” in contrast to the “proud and … just hero and loyal vassal, Miloš Obilić.”11

The Christianization of the legend of Kosovo was in some respects present from the start, but it evolved over time, becoming especially pronounced in the nineteenth century. At that time, a cult grew up around Miloš Obilić that the Serbian Orthodox Church officially recognized.12 Also, the supper hosted by Lazar on the eve of the battle took on more and more of the attributes of the biblical Last Supper, with Lazar portrayed as Christ surrounded by his disciples (in some renderings explicitly numbering twelve), among whom one, Vuk Branković, was a Judas figure.13

Another aspect of the legend’s Christianization was its close association with St. Vitus’s Day. This holiday, also known as “Vidovdan,” was celebrated on June 28, the same date as that on which the Battle of Kosovo was fought. On the eve of St. Vitus’s Day, it is said, Serbian family heads would give each household member a peony as he or she left to take part in the festivities, saying, “I want you to be as red and strong as this flower,” in reply to which the recipient would say, “I shall be as those who shed their blood on the Field of Kosovo.” In the late nineteenth century, when St. Vitus’s Day became an important day in the church calendar and for the first time a Serbian national holiday, stories circulated in Kosovo “about the rivers Sitnica, Morava and Drim, which would turn red as blood on St. Vitus’s Day”—a phenomenon that would be repeated until “the revenge of Kosovo and its complete liberation from the Turkish yoke.”14

KOSOVO: HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Before discussing the full maturation and crystallization of the Kosovo myth in the nineteenth century, both in response to and as a shaper of modern Serbian nationalism, we need to sketch the history of Kosovo over the previous half-millennium or at least to identify some of its more salient themes. The traditional Serbian view is that the Kosovo region, from the Slav invasions of the fifth and sixth centuries until fairly recently, was predominantly Serb. Albanians, however, claiming descent from the ancient Illyrians, who inhabited the area long before the arrival of the Slavs, argue that Kosovo is their ancestral home, not that of the Serbs. Likening the debate to that surrounding the Palestinian issue in recent times, Julie Mertus suggests that, in truth, Kosovo is integral to the “competing national identities” of both peoples.15

Up until the late twelfth century, Kosovo was part of the Byzantine Empire. In the 1180s, however, Serbia, under the new Nemanjic dynasty, was able to conquer the Kosovo region and penetrate into northern Macedonia, gaining control over a substantial stretch of territory. Soon thereafter (in 1219), an event of enormous importance for subsequent Serbian history took place with Byzantium’s acquiescence in the establishment of an autonomous Serbian Orthodox Church. The national church, which achieved full independence in 1346, became a staunch supporter of the Serbian state in the years prior to the Ottoman conquest and during the centuries of Turkish rule was an energetic proponent of the idea that Serbia—like Christ—would be resurrected. Most of the Serbian monarchs were canonized, their images incorporated in late Byzantine frescoes (often of exceptional quality) on the walls of Serbian churches and monasteries. “So, for hundreds of years,” Tim Judah observes, “the Serbian peasant went to church and in his mind the very idea of Christianity, resurrection and ‘Serbdom’ blended together.”16 In the mid-fourteenth century, Stefan Dusan took advantage of the straitened circumstances that had befallen the European areas of Byzantium to overpower the Albanian-speaking lands (including the territory now known as Albania). The evidence suggests, however, that at least up to the time of Lazar and probably beyond Albanians constituted only a minor part of the population of Kosovo.17

During the four and a half centuries of Ottoman rule (1455–1912), a number of important changes ...