eBook - ePub

Ms. 45

About this book

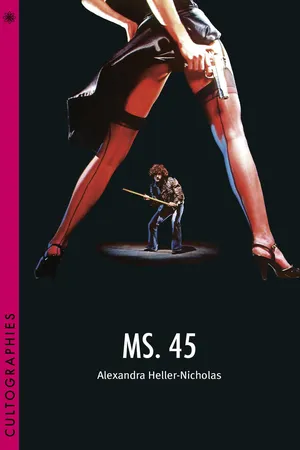

Despite its association with the broadly disparaged rape-revenge category, Abel Ferrara's Ms. 45 is today considered one of the most significant feminist cult films of the 1980s. Straddling mainstream, arthouse, and exploitation film contexts, Ms. 45 is a potent case study for cult film analysis. At its heart lies two figures: Ferrara himself, and the movie's star, the iconic Zoe Lund, who would further collaborate with Ferrara on later projects such as Bad Lieutenant. This book explores the entwining histories and contexts that led to Ms. 45's creation and helped establish its enduring legacy, particularly in terms of feminist cult film fandom, and the film's status as one of the most important, influential, and powerful rape-revenge films ever made.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Film & Video1

PRIMA FACIE – TOWARDS MS. 45

Before looking at the film more closely and unpacking the mechanics of its perhaps surprisingly complex ideological nuances, the practicalities of Ms. 45’s production give insight into how this particular movie exploded out of this specific context. This chapter explores the circumstances surrounding the making of the film and the relationship between Tamerlis Lund and Ferrara, but the centrality of New York City itself to the movie cannot be underestimated.

Filmed on location across iconic New York City locations such as SoHo, Little Italy, Central Park, the Garment District and the East Village, J. Hoberman noted that ‘Ms. 45 is drenched in local color’ (2014: 17L). There is an energy, vibrancy and immediacy to Thana’s New York City, and it is arguably this aspect that offers such an immersive, often-overwhelming experience when watching the film, even over thirty years later. With little regard for official permits or licences, Imran Khan has suggested the film was shot in line with a guerrilla filmmaking approach that resulted in remarkable verisimilitude, where ‘everyday life in the city is caught in moments of genuine discord’ (2014). The release of Ms. 45 came just over three years after the arrest of David ‘Son of Sam’ Berkowitz, a serial killer also known as the ‘.44 Caliber Killer’ who began terrorising the city during the summer of 1976. From this perspective, Thana’s eponymous nom de plume recalls for that city at this particular historical moment the name of the film alone revived real fears. Hoberman rightly suggested these made Ms. 45 broadly ‘redolent of urban anxiety’ (2014: 17L). Ferrara’s memory of New York City during this era was also closely linked to his filmmaking practice: ‘The New York of the ‘70s was a crazy place, man,’ he said. ‘Dirty and gritty, with punk-rock and hardcore bands. Making a movie was an extension of all that’ (Petkovic 2014).

So closely is Ferrara’s auteurist brand associated with New York City that for Rich Juzwiak at Gawker, talking to the filmmaker was ‘about as close to having a conversation with a human embodiment of pre-Giuliani New York as you can get’ (2013). With his trademark linguistic flourishes (phrases like ‘ya dig?’ and a steady stream of f-bombs), Ferrara has long captivated interviewers with his tales of pre-9/11 New York. In a 2013 interview, Ferrara described the city as he remembered it earlier in his career: ‘When we made Driller Killer, there was a hobo camp on Fifth Avenue and 18th Street. We didn’t have to bring those bums in for the film, they were right downstairs’. He continues, ‘I remember when Union Square was a war zone’ (Abrams 2013). The Driller Killer and Ms. 45 are linked closely to this vision of New York City, one where Ferrara has recalled being given advice from a New York City police officer about a particular region in the Lower East Side: ‘The mugging rate is 100%, so don’t worry about it. You walk down there, you’re going to get mugged’ (Dollar 2013).

Yet as Philippe Met has argued, New York City functions in Ferrara’s films well beyond a token signature setting. Rather, as he suggests, it ‘appears as a stage or, better still, an arena: a tragic circular space where a choreographed ritual, that of an individual and/or a community, will unfold, with sometimes all the trappings of a danse macabre’ (2013). Identifying the numerous New York City locales in which the film’s action plays out – from the Garment District to Central Park to Midtown – Met suggests that ‘what is ultimately at stake is a form of circulation through the maze of New York streets’. What is of interest, then, is less ‘New York’ as a single conceptual space that ‘represents’ any singular notion of urbanity-in-crisis, but rather how Thana negotiates her identities – and embodies her trauma – across these shifting locations. At stake is New York City itself as much as the idea of New York City: as Tamerlis Lund herself noted in an interview to promote Bad Lieutenant, ‘New York is both fact and fantasy, a place where just about any sort of destiny can be played out’ (Macaulay 1992/1993). And as it turned out, New York City was the perfect location for her and Ferrara’s revenge fantasy Ms. 45 to play out.

PLANNING THE CRIME: MAKING MS. 45

Ferrara has identified Woody Allen, John Cassavetes, Stanley Kubrick, Samuel Fuller, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and of course Pier Paolo Pasolini (Lim 2009; Carli 2009; Terenzi n.d.) all as influences on his filmmaking practice at different points of his career, the latter whom was the subject of Ferrara’s 2014 biopic. Many critics have cited the influence of Roman Polanski on Ms. 45, particularly his 1965 psychological thriller Repulsion (Axmaker 2013; Pettersson 2002; Hoberman 2014: 17L). While Polanski’s film primarily occurs in a single location and focuses on the increasing detachment of its protagonist from reality in the context of what is explicitly a domestic space, Ron Pettersson has rightly noted similarities between Thana and Catherine Deneuve’s Carol Ledoux, ‘who barely speaks, suffers from a pathological fear of rape, and mentally deteriorates in a house’ (2002).

The influence of Martin Scorsese on Ms. 45 also stands out for a number of reasons, most typically Thana’s Taxi Driver-inspired ‘You talkin’ to me?’ homage near the film’s conclusion. Ferrara has spoken warmly of Taxi Driver, and adopted a Travis Bickle-style mohawk when he was sixteen years old out of love of it (Gregorits and Speiser n.d.). Ferrara’s empathy for De Niro’s protagonist perhaps indicates the source of his compassion for Thana: ‘I think that movie is greatly misunderstood by a lot of people’, he said. ‘Everyone seems to regard that character as a psychotic. I thought he was a sweetheart’ (ibid.). But as Emanuel Levy has suggested, the association is far more than simple homage: ‘Abel Ferrara has taken Scorsese’s thematic and stylistic concerns to an extreme, which is why he has never gained wider acceptance’ (1999: 119). Aside from Taxi Driver, Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973) and Raging Bull (1980) provided Ferrara with insight into how the seedier underbelly of New York was being represented at the time: along with the films of Woody Allen, Ferrara has said he had a strong awareness of ‘a very heavy criteria for what it’s supposed to look like…so hey you want to fucking be a New York film maker, you better at least aspire to an A game’ (Jagernauth 2013).

While these more abstract qualities of New York City cannot be underplayed, it was the real world where the Ms. 45 project came together. In 2014, Ferrara encapsulated the position that he and his colleagues found themselves in after The Driller Killer: ‘Ms. 45 was one of those films where we were still kids, you know. We were still trying to make it in the world, and just going at it with a lot of wide-eyed wonder. We were very pre-jaded.’ He continues, ‘I think Ms. 45 was the first film where we went, “Jesus Christ, people are actually gonna make money from this – we’d better fucking concentrate here”’ (Goodsell 2014). This shift from the underground towards a wider audience was therefore a conscious decision for Ferrara and his collaborators. ‘We were trying to bust out’, he said in 2013, ‘You know we were trying to make a name for something, we were trying to basically come up in the world of making movies’ (Jagernauth 2013).

It was in this context that Nicholas St John’s script proved to be a blessing for Ferrara. The director was unaware that St John was working on a new script after The Driller Killer, and St John himself had no instinct for whether the project was even viable (Gallagher 1989: 54). When Ferrara received the script in the mail, his decision to move ahead was an easy one: ‘Everyone who read it loved it, so I was like, “Yeah, let’s go”’ (Hays 2001). This script came to him fully formed from St John – ‘shot-for-shot, line-by-line’ (Gallagher 1989: 54) – and according to Ferrara, ‘the movie you see came right off of his typewriter’ (Gilchrist 2013). Ferrara has emphasised that he ‘didn’t change anything’, and that the film on screen was loyal to this original script: ‘I don’t even think Nicky was around when we shot that? He didn’t have to be there: he wrote what you saw’ (Abrams 2013). According to cinematographer James Lemmo, however, the script itself was necessarily thin: ‘Ms. 45 had only a 36 page outline’, he told Brad Stevens. ‘Nicky would provide dialogue from time to time, but the main character didn’t speak, and the other characters really had nothing to say: the film wasn’t heavy on plot, it was moments loaded with circumstances, expressed cinematically’ (Stevens 2004: 60).

Although in love with the script, Ferrara knew that the success of the project depended on casting. ‘It was a beautiful script’, Ferrara has said, yet at the same time he felt it came off as ‘cold’. It was Tamerlis Lund, he has noted, that ‘gave it a heart and soul’ (Jones 2003: 67). Tamerlis Lund herself has described her discovery as somewhat ‘banal’: the young ex-musical protégée was at an avant-garde gig in New York City. She described what followed to Nicole Brenez and Agathe Dreyfus:

At that moment someone gave me a card, a card about a box of films (it was not Abel). Since I wasn’t an actress I had very little interest in all that but I said ‘OK’, it was just for fun. But I went to an audition, I did the thing. I didn’t have a headshot, so I went to 42nd Street to make photos, a strip of six shots and I handed them in. I thought it was over, forgotten, I forgot all about this cinema story. (Brenez and Dreyfus 1996)

Abel Ferrara appearing as an unnamed rapist and Thana. Credit: Navaron Films / The Kobal Collection

‘At the same time Ms. 45 was in preparation’, she continued. ‘Some friends came with me to the audition…But it wasn’t really an audition, rather an interview; there was a more normal audition then, then another, and another, and I got the role of Ms. 45’ (ibid.). From Ferrara’s perspective, however, this was hardly a case of the young Tamerlis Lund being ‘discovered’ per se: ‘When I met her, she was a seventeen-year-old superstar’, he has said. ‘She was already going to college, she had guys following her around, she was running a revolutionary cell. She was a musical prodigy, a brilliant writer, the whole nine yards’ (Reynolds 2002). Meeting Tamerlis Lund when she was at Columbia University on a music scholarship, Ferrara said in an interview on the 2014 Drafthouse Films home entertainment release that her confidence was overwhelming: ‘she was basically auditioning me’. Although St John’s script was close to the final picture of what the finished movie would be, the discovery of Tamerlis Lund was essential to the project’s success. ‘It was just a matter of finding a woman’, said Ferrara. ‘Thank God Zoë appeared’ (Abrams 2013).

Like Tamerlis Lund, the bulk of the film’s primary cast were new to the screen, including Albert Sinkys who played her lecherous boss, and Darlene Stuto, who played her friend Laurie. Peter Yellen – who played the film’s second rapist who assaults Thana after she returns home after her first attack to find him attempting to burgle her apartment – had appeared briefly as a derelict near a bus stop in The Driller Killer, and would be involved with the music for a number of Ferrara’s films including King of New York (1990), China Girl (1987) and Bad Lieutenant. And not everyone in Ms. 45 was an unknown: most obvious is the appearance of Editta Sherman as dog owner and nosy neighbour Mrs. Nasone. Sherman’s reputation was built around her career as a photographer and activist, but she was also a model for artists including Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey and Francesco Scavullo. Sherman was such a key player in the legendary New York bohemian Carnegie Hall Artist Studios for over half a century that she was renowned as the ‘Duchess of Carnegie Hall’, and her inclusion in Ms. 45 brings a distinct aspect of New York City’s culture of that period to life. According to Ferrara’s creative consultant Joe McIntyre in an interview on the 2014 Drafthouse Films home entertainment release, it was through Sherman that the production was able to access Carnegie Hall as the location for the final climactic Halloween party. While Sherman’s performance is one of the most memorable and eccentric in the film, the suggestion that Ferrara originally wanted to cast Divine as the landlady to garner the film added cult appeal is a tantalising one.1

Estimates for Ms. 45’s budget range from $62,000 to $350,0002, but economic specifics aside there is little doubt that it was a low-budget affair. Yet something about the film’s very status as a low-budget independent film worked in its favour: this was a climate where investors were aware that a film like Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre could cost $300,000 and still return $3 million, so the interest was there. Says Ferrara, ‘I could take that to everybody I knew and say, “Hey, man, if we can’t make a film as good as Texas Chain Saw, we better hand our diplomas back,” whether we even had them or not’ (Dollar 2013).

It may not therefore have been wholly untrue when Myron Meisel dismissively noted that Ms. 45 was made ‘by some obviously hustling New Yorkers’ (1983). Yet many of the team that brought Ms. 45 to the screen had worked with Ferrara in the past, and would go on to collaborate with him in the future. A key name here is St John himself: although making two small appearances in early Ferrara films (in 9 Lives of a Wet Pussy as a chauffeur, and as a detective in Ms. 45), St John’s reputation comes from his role as Ferrara’s primary collaborator and screenwriter. Having grown up together, St John is responsible for a vast number of Ferrara’s scripts, including the shorts Nicky’s Film in 1971 (a film named after him) and The Hold Up (1972), and the features 9 Lives of a Wet Pussy, The Driller Killer, Fear City (1984), China Girl, King of New York, Body Snatchers (1993), Dangerous Game (1993), The Addiction and The Funeral (1996).

Mary Kane is another long-time Ferrara collaborator, beginning her association with him as a production manager for The Driller Killer. She would work with Ferrara in a number of other production capacities – production manager, associate producer and producer – across some of his most well-known and critically acclaimed later films, including Fear City, China Girl, King of New York, Bad Lieutenant, Dangerous Game and The Funeral (1996). Associate producer Richard Howorth appeared in The Driller Killer as Stephen (Carol’s husband), and was also an editing assistant on Ms. 45. The year Ms. 45 was released, he would work as a dialogue editor in another cult classic, Steve Miner’s Friday the 13th Part 2. Executive producer Rochelle Weisberg had worked with Ferrara numerous times already in the same capacity on The Driller Killer, as well as on Stu Segall’s Drive In Massacre (1977), a low-budget attempt to cash in on Peter Bogdanovich’s Targets (1968). She was also the uncredited producer for 9 Lives of a Wet Pussy.

Cinematographer James Lemmo is listed in the Ms. 45 credits as James Momel, and he was also credited in the art department crew for The Driller Killer as Jimmy Spears for ‘inspirational art: photography’. Lemmo would go on to work on a number of cult director William Lustig’s horror films, including Maniac Cop (1988), Maniac Cop 2 (1990) and the Judd Nelson vehicle Relentless (1989), as well as Joe Giannone’s slasher Madman (1982), recently reappraised thanks to a 2015 Blu-ray release by boutique cult film distribution company Vinegar Syndrome. Christopher Andrew was another Ferrara regular who began his collaboration with the director with Ms. 45 (not only as art director, but as a co-editor on both sound, vision and music). Andrew would continue to work with Ferrara over the next decade in a variety of capacities on films including King of New York, China Girl, and Cat Chaser (1989).

Jack (also known as John) McIntyre is another Ferrara regular, beginning his collaboration when he appeared in bit parts in the short The Hold Up and The Driller Killer, and doing sound on both of those films and another early Ferrara short Could This Be Love (1973), as well as 9 Lives of a Wet Pussy and of course Ms. 45. Jack McIntyre had known St John and Ferrara since the late 1950s, and is credited as a ‘creative consultant’ and other miscellaneous roles on a number of Ferrara’s films. McIntyre wrote the song ‘Grand Street Stomp’ for The Driller Killer soundtrack, and is also credited on Ms. 45 for ‘special effects’. His name would appear in different capacities on a number of other Ferrara projects in including China Girl, Cat Chaser, King of New York, Bad Lieutenant, Body Snatchers, Dangerous Game, The Addiction, The Funeral, New Rose Hotel, and ‘R Xmas (2001). McIntyre was joined on special effects duties for Ms. 45 by Matt Vogel, who although only working with Ferrara twice again – on China Girl and King of New York ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Mea Culpa

- 1 Prima facie – Towards Ms. 45

- 2 Locus delecti – Watching Ms. 45

- 3 Modus operandi – After Ms. 45

- 4 Post mortem – Beyond Ms. 45

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ms. 45 by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.