![]()

PART I

Fluid Dynamics of Wine Tasting

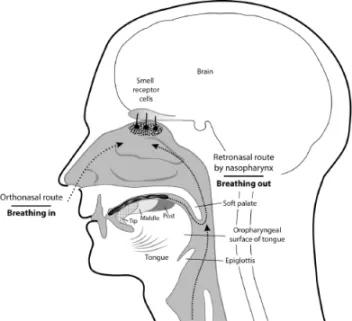

Most books on wine tasting focus on the sensory sensations because that is what we are most aware of. However, as indicated in the introduction, all the sensations created by the brain are due to the movement of the wine in our mouth and throat and the movement of the volatile molecules released into the air in our respiratory tract. The relations between them are shown in figure I.1 for an instant in time when the wine drinker has wine in the mouth and is breathing at the same time. These movements generate the activity that stimulates the brain. This figure will thus serve as a reference for explaining in the rest of the book how the brain creates the taste of wine.

The Fluid Dynamics of Wine and Volatiles

The movement of wine and its volatiles invites study by the principles of fluid dynamics—the flow of liquids and gases in nature. As applied to liquids it is called hydrodynamics and is essential for constructing efficient water supplies and moving oil from refineries. In wine tasting, moving the wine requires propulsion by the muscles of the mouth and throat, involving the activity of many muscles. Although we are usually unaware of them, these muscles are among the most complex in the body. Understanding their principles can therefore add greatly to our experience of wine.

FIGURE I.1

The human head, showing the oral cavity (mouth) and respiratory tract (shaded) and the brain above. Wine moves from the tip to middle to posterior sites on the tongue. The airway flow dynamics for sniffing in (orthonasal smell) and breathing out (retronasal smell) are indicated by arrows.

From a broad perspective, these muscles are involved in transporting and processing three types of food. One is solid food, such as plants, meat, and seeds, which require active chewing and reduction to a mash before swallowing. Another is water, which is usually simply ingested and swallowed. Both of these activities are essential for nutrition and survival. The muscles of the mouth and throat are assumed to have adapted over millions of years of prehuman and human evolution to handle efficiently both food and water. It will therefore be worth our while to understand these basic mechanisms.

The third type of food is flavored fluids; in our case, wine. Wine is a food that is consumed almost entirely for its flavor, with little nutrient value. Wine making developed only in the last several thousand years, too brief a time to have a significant impact on human evolutionary adaptation. When we drink wine, we therefore use the mechanisms for eating that are essential for survival and adapt them for pleasure. We will focus on the principles that have emerged from this research on food in the mouth and show how they can be applied to wine.

BOX I.1

The Main Steps in the Fluid Dynamics of Wine

Taking a sip

Mixing with saliva

Movements of the tongue

Movements of the mouth and jaw

Gating by the soft palate

Gating by the epiglottis

Swallowing

In addition to moving the wine we need to understand the transport of volatiles released from the wine into the air in the respiratory tract. As already mentioned, this respiratory flow is essential, first, for sniffing in, called orthonasal smell, which is the aroma of what we are about to eat or drink, and second, for breathing out to carry the aroma from the wine in the mouth and throat to the nose during expiration, to add retronasal smell to the total sensation of flavor from the food in the mouth. We will consider the muscles involved in producing both of these contributions to the flavor of wine.

In this new approach to understanding wine tasting, we have indicated the overall sequence of events that takes place. This sequence can be broken down into steps. Some of the steps occur one after the other, while others overlap. Some involve the flow of the wine, and others involve the flow of air. The steps involved in the movement of the wine are summarized in box I.1.

The Composition of the Air

The two kinds of air in orthonasal and retronasal olfaction have interesting similarities and differences. Orthonasal air comes exclusively from the environment and consists of the gases nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon dioxide, together with evaporated water varying with temperature and humidity. It includes various trace compounds, depending on the local environment and levels of pollution, as well as particulate matter, such as smoke, pollen, dust, and lint. Finally, it contains many different types of volatile molecules, depending on our activities, that come from industrial exposure to open nature to mealtimes when we are sampling the scents of food and drink. Although not often noticed, at high levels these external conditions can distort flavor perception, as in smokers and in polluted environments.

Retronasal air, in contrast, reflects the characteristics of the expiring air that contains contributions from inside the body after it is filtered by the upper airway. In addition to nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon dioxide, it has high humidity due to moisturizing by the airway mucus membranes and a warm temperature due to the body’s temperature. Among its trace elements are the volatile compounds that have been breathed in, and those called endogenous volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that come from metabolic processes in the body. Although not usually considered significant, we will mention three—acetone, isoprene, and alkanes—that may seem surprising to find in the body and are of possible relevance to wine tasting.

Acetone is actually an industrial solvent. It is produced by glucose metabolism and circulates in the blood in trace amounts. It is raised in high-fat, low-carbohydrate diets. It is especially high in diabetes and alcoholism and may be raised during pregnancy and nursing.

Isoprene is slightly fragrant. It is produced by many trees and plants and therefore present in inspired air. (As a polymer, it forms the basis of rubber.) In the body, cholesterol metabolism produces the molecule; it is a subunit of vitamin A and involved in photoreception in the retina. It is present in exhaled air; humans smell slightly of isoprene.

Among the alkanes, the simplest is methane, produced by intestinal digestion and a contributor to global warming through millions of domestic animals.

Finally, it may be noted that the ingestion of wine itself puts an increasing load of alcohol in the blood, which lends a characteristic sweet fragrance to the exhaled breath.

These substances enter retronasal smell via several routes. One is by diffusing from the lung capillaries into the air in the tiny pockets called alveoli that make up the lung. Another is by seepage into the airway within the lung, trachea, and pharynx. And a third is from the wine in the mouth, as we shall see.

In summary, inhaled air and exhaled air are similar in their basic gases but have distinct combinations of volatile molecules from the environment and from the body. For neuroenologists, two questions seem particularly interesting. First, can these differences in volatile molecules contribute to differences in the wine aromas of orthonasal compared with retronasal smell? Second, can they contribute to the differences in sensitivity to smell between the two routes? These questions deserve further study.

The pattern in normal people can vary under different conditions of age and health. For example, a study of centenarians found differences in VOCs compared with younger populations. And many studies have documented the effects of different diseases. Kidney failure; cancer; and neurodegenerative, neurological, and psychiatric disorders cause metabolic and related changes: the blood can convey these metabolic effects to the lung and out into the exhaled air. It is possible that these changes can be detected as early signs of these disorders and could impinge on the aromas sensed in wine tasting. Evidence that isoprene and acetone can vary in the exhaled breath under different emotional states suggests that this could be an area of active research in the future.

The Airflow Dynamics of Wine Volatiles

Airflow dynamics engineers study physical devices such as airplane wings and heating systems in order to design optimal airflow patterns. The flow of volatiles in wine tasting is fast enough for these principles of airflow dynamics to be applicable. Scientists have already begun to apply this analysis to airflows in the nasal cavity during orthonasal smell. Here we expand this approach to embrace the flows not only in the nasal cavity but also in the nasopharynx and oropharynx (throat), during both orthonasal and retronasal smell. This is a step toward creating a new field of wine volatile flow dynamics, which will help to move the mouth and throat from our general ignorance about their structure and function into the mainstream of research on the human body.

BOX I.2

The Main Steps in Airflow Dynamics of Wine Volatiles

Sniffing in: orthonasal air currents in the nose

Breathing out: retronasal air currents in the nose

Breathing out: movement of volatiles from the mouth

Breathing out: movement of retronasal air currents from the pharynx

Breathing stopped: during the swallow

Breathing out: the “flavor burst” and “finish” after swallowing

Engineers develop flow dynamics on a highly quantitative basis, but we will use it mainly on a qualitative basis, to explain the principles involved (box I.2). This will reveal a much richer understanding of how the perceptions of wine tasting arise when we take up the steps of sensory processing.

The stages of moving the wine through the mouth end with the automatic act of swallowing, which forces the wine from the mouth into the throat and through the throat into the esophagus. This leaves a coating of wine on the mouth and throat, whose volatiles are swept up by the respiratory system and transported to the nasal cavity.

BOX I.3

Controversies About the Fluid Dynamics of Wine Tasting

How does the fluid dynamics of wine tasting compare with the fluid dynamics of food and water in the mouth?

What are the stages of fluid dynamics in the mouth, from the initial sip to swallowing, and how are they related to the sensory experience?

To what extent are the differences in evaluating wines due to differences in fluid mechanics or differences in individual brains?

Wine volatiles arise from the mouth and, after swallowing, from the mouth and throat. Which makes the greater contribution to the taste of wine?

In this part, on muscles and flows, we begin in chapters 1 and 2 with the fluid dynamics of the wine in the mouth as a basis for stimulating the sensations of mouthfeel and taste as well as producing the volatiles. Chapters 3 and 4 consider the fluid dynamics of the volatiles in the respiratory tract that produce orthonasal and retronasal smell. Chapter 5 describes the swallow and its aftermath, which make a large contribution to retronasal smell and the wine aroma. This is the final step in the wine-tasting experience.

Given the many factors involved in muscle actions and the many routes for the dynamic flow of fluid and volatiles, it is not surprising that unsolved problems and controversies exist. Box I.3 summarizes a few of them. We will find answers and raise new questions in the following chapters.

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Sip and Saliva

Fluid dynamics of wine in the mouth, we have seen, means the factors that move the wine from the initial sip through the mouth to the throat and into the esophagus and stomach. This entire sequence, from sip to swallow, is called deglutition (literally, the transport of contents out of the mouth). The key questions for neuroenology are, first, how the fluid stimulates the mouthfeel and taste systems in the mouth and, second, how it gives rise to volatiles that contribute to the wine taste through retronasal smell.

Modern studies of deglutition started in the 1950s and focused mos...