![]()

II

EXAMINING THE PATHWAYS THROUGH THE THICKETS

![]()

6

ALWAYS MORE PEOPLE AND EVER MORE ELDERLY

Caring and Paying

While exceptions can be found, many of the most prominent writers and researchers on global warming, food, and water put a reduction of population growth rates high on their list of priorities. And why not? More people mean more consumption of everything needed for our collective lives and survival, some of which can never be recaptured or replaced. More people will add to the environmental pollution already being wrought on our planet, further threatening those already alive and jeopardizing generations to come. More children born to mothers hard-pressed with too many children already harms everyone—mothers, children, and fathers.

I propose an alternative way of thinking about population growth, adding to the mainline story a neglected or too readily minimized feature, that of the parallel growth of aging in rich and poor countries alike. That important difference throws a provocative light as well on the rising obesity and chronic illness in developing countries that is coming to be part of that aging process. In turn, that combination—the coming size of populations and the relatively new important additions of aging and new health risks to the elderly—opens the door for a fresh examination of the growth of gross domestic product (GDP). As matters now stand, we might recall, there is an argument between those who think of strong GDP growth as necessary for national and global welfare, and those who believe it to be a significant cause of our global environmental and health problems. In many ways there is considerable overlap among population growth, aging societies, and GDP growth.

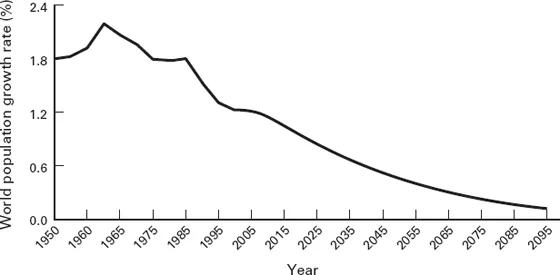

POPULATION

In 2011 the world saw population growth move past the 7 billion mark. In 1960 there were 3 billion people, in 1974 there were 4 billion, and in 1987 there were 5 billion. The number of births in 2013 is estimated to be 86 million.1 In the late 1960s the annual population global growth rate was 2% but has now declined to 1.14% and is expected to decline still further in the future, to less than 1% by 2020 and less than 0.5% by 2050 (figure 6.1). Even with low birthrates, populations will continue to grow for a time. The United Nations Fund for Population Activities, revising upward earlier global figures, projected 9,725 million people in 2015 and 11,213 in 2100—but with a 2.0 total fertility rate (TFR), with most countries at 1.8.

Asia has 60% of the world’s population, 3.2 billion, and is growing at an annual rate of 1.03%, and Africa has 15.5%, some 1.1 billion, but has the fastest annual growth rate at 2.46%. At the other extreme is Europe, with 742 million and 7% of the world’s population, and a projected decrease of 4% by 2050; and North America with 355 million, some 5% of the global total, and a projected increase of 26% by 2050. China, with 1.385 billion people and India with 1.252 billion have the largest populations, with the United States in third place with 320 million. Projections can, of course, differ, with higher or lower numbers: the future has its own logic, best discerned in hindsight.

FIGURE 6.1

World population growth rate (%). (World Population Clock: Seven Billion People (2013) Worldometers, www.worldometers.info/world population, accessed 10/25/15)

Thomas Robert Malthus (1776–1834) was the first to bring population growth to public attention. His Essay on the Principle of Population, which went through many editions and emendations, was both influential and controversial. His leading principle was that “population, when unchecked, increases in a geometric ratio,” while “subsistence only increases in an arithmetical ratio.” As the resources for survival increase, population increases as well, and this combination in turn stimulates increased productivity. But productivity cannot indefinitely keep up with population growth. At some point, Malthus argued, it must stop and be limited. While in general this argument has been rejected, in great part because of technological improvements in productivity, renewed echoes of it can still be found in current discussions of high birthrates in the poorest of nations, notably in sub-Saharan Africa.2

If a shortage of food does not necessarily lead to lower birthrates, there are two variables that have historically been most determinative: a decline in death rates and a rise in income.3 That fact does not mean that present birthrates are so rigidly determined. Many other causes influence contemporary birthrates, but the original historical momentum, going back some centuries, was a decline in mortality, followed by an increase in income and a rising GDP.

Stages of Population Growth

Historical demography has made use of a transition model. Stage 1, the premodern phase saw a balance between birthrates and death rates, with a population growth rate that could take 1,000 to 5,000 years to double. Average life expectancy was about thirty years, with an exceedingly high infant mortality contributing heavily to that low average; but even those who survived childhood would be lucky to make it to age fifty. Stage 2 saw a decline in death rates in developed countries (particularly for infants) that began at the end of the eighteenth century but with birthrates remaining high. Poor public health in the premodern era gave way to nineteenth-century improvements in sanitation and clean water supplies, aided by better and more reliably produced food, helping to account for the mortality decline. In 1880 there were only 1 billion people on earth. The numbers would soon start rising sharply.

Stage 3, the industrial era of modern societies (roughly 1870 on), saw a steady decline in death rates and a parallel decline in birthrates. Stage 4, the so-called postindustrial era, our own, has seen a continuation of that decline, with the greatest drop after World War II, and particularly since 1970. The decline of agriculture and the rise of urbanization during stage 3 meant a sharp drop in the need for large families to keep traditional family structures and domestic economies going and a growing need for more education for the young for life in a postagricultural, industrial society. Old age care gradually moved from the family to the state, particularly in northern Europe, although southern Europe saw a continuation of older traditions of family care.

As death rates dropped and family life changed so also did the role of women, greatly stimulated by improved education, a shift that got under way in the late nineteenth century and accelerated after World War II. The greatly improved contraceptive technologies of the twentieth century helped to accelerate the trend to lower global birthrates, already well under way before reliable contraceptives emerged. “The eventual family and sexual mores of an industrial society depended upon controlled fertility,” the demographer John C. Caldwell has noted, “but there was no widespread demand for this until mortality, especially infant and child mortality, fell.”4

If a decline in death rates was the initial driver of a decline in birthrates, industrialization, accompanied by urbanization, was its sustaining engine. Industrialization brought with it a rapid growth in income and affluence. Per capita global income in 1820 was less than double its level in 1520, but had tripled just prior to World War I and by a multiple of fifteen by the end of the twentieth century.5 As incomes rose, birthrates declined (with the exception of the baby boom era). With affluence and intensified industrialization came the secularization of much of life in the twentieth century, accelerating the decline. What Caldwell has called “agricultural morality,” which required high birthrates, passed away, and in its place came the advent of high divorce rates, increased cohabitation, later marriages, and a large proportion of women in the workplace.6 Beginning in the 1870s or thereabout, fertility gradually declined.

Even though the decline in mortality might be characterized as a macro-shift, of universal importance and influence (along with, as we will see later, affluence), it is also true that the fertility transitions in various countries are both similar and diverse. In the United States, fertility transitions, though obviously influenced by declining mortality, have taken a slightly different route than in western European countries, and are only just now declining, with a total fertility replacement rate (TFR) level of 1.8 children in 2014.

After fertility began to decline around 1870, it steadily dropped through the first half of the twentieth century. By the 1930s, and particularly in 1933 (my wife’s birth year), the U.S. birthrate was 1.8 children per woman (approximately what it is now for white women), below, though not strikingly so, the 2.1 replacement level. By the early 1900s, that decline was picking up speed, and in the United States some 25% of women born in 1909 had no children at all (compared with approximately 20% now). The 1930s were the prewar nadir in developed countries—that era when those born just before and after the turn of the century came into their childbearing years. My father’s Catholic family in that era had eleven children, nine of whom married. They procreated a total of nine children. Economics trumped theology.

The Pre–World War II Specter of Population Decline

It did not take long for some widespread anxieties about the dropping birthrates to appear. France has long been noted for its concern about population decline and remains an interesting bellwether country to this day. It was the first country in Europe to take declining birthrates seriously, if for reasons that now seem distant and antique—military might. Wars required large numbers of soldiers; they were the key to victory. In the 1870s, in the aftermath of the French defeat in the 1870–1871 Franco-Prussian War, as Michael S. Teitelbaum and Jay M. Winter put it, “the population question [became] a permanent part of the rhetoric and, on occasion, the substance of French politics.”7 The military focus remained strong for decades and particularly in the years just prior to World War II when Germany was again rising to power. Remarkably enough, despite the hand-wringing, the French birthrates were still high by contemporary European standards. Not until 1975 did the French birthrate drop below the 2.1 replacement rate (and not by much); for many decades after 1870 French TFRs were in the range of 2.4 to 2.8.

Even so, the rhetoric of the anxiety was remarkably similar to that voiced by various American conservatives in recent years in light of much lower birthrates. A Jesuit priest in the 1870s saw the decline as God’s punishment for the sin of contraception (which was hardly very effective at that time). Later figures spoke of low natality as a “disease,” an “increase in feebleness,” an instance of “how a nation dies,” a “refusal of life,” “demographic bankruptcy,” and “biological degeneracy.”8 The more common phrase these days, bemoaning much lower birthrates, is that of national “suicide,” but the flavor is identical. Ironically, it is family-friendly France—condemned by many religious conservatives in recent years for its flagrant and official secularity—that has become the one of few developed countries on the Continent to bring its birthrate back to over 2.0 in 2010, although that number had fallen back to 1.99 by 2013.

BABY BOOM AND BABY BUST

The long decline in the American birthrate, beginning in the late nineteenth century and peaking during the years of the Great Depression, ended with a sudden upswing of births in 1947, dramatically so in the United States and Canada, but strong in other developed countries as well. The U.S. birthrate almost doubled between the 1930s and the 1950s. In Europe during that period it rose by 13% in the United Kingdom, 17% in Italy, 28% in West Germany, and 35% in the Netherlands.9 Except for the economic security of that period, no theory has fully managed to explain the baby boom period (1946–1964). It was a surprise in its coming, anticipated by neither governments nor demographic experts, and no less surprising in its rapid demise. As the historian Tony Judt noted, “Now—even before post-war growth had translated into secure employment and a consumer economy—the coincidence of peace, security and a measure of state encouragement sufficed to achieve what no amount of pro-natal propaganda before 1940 had been able to bring about.”10 If economic security played a large role, it does not explain the increase in earlier and near-universal marriage and a larger portion of women having two children. Families of three to four increased, but the number of those having five or more actually declined.11

If the primary source of fertility decline beginning in the 1870s was a combination of declining mortality and rising affluence, the baby boom era was an anomaly. Once it was over, birthrates resumed their downward course. But why did the baby boom era come to an end? Some leading economists looked for an answer to that question. The economist Gary Becker offers a different account. He contends that time itself has a monetary value, and in the postwar years, rising education levels and income growth meant that time taken out to raise children had an economic cost. That time could otherwise be used to increase earnings.12 A number of other factors were converging as well. The economy in the 1950s and 1960s in the United States was also becoming more complex, requiring more workers with more education. Women’s education was likewise on the rise, not only opening the way for more and better work outside the household but also stimulated by the rise of feminism. Meanwhile, there was a sharp increase during that period in consumption, more people living more affluent lives and buying a whole host of goods, from refrigerators to TV sets to increased air travel. Houses were more plentiful and growing in size; suburbs, with accompanying large shopping malls, were expanding; and two-car families were on the rise.

The demographer John Caldwell adds another twist: “The basic story of the collapse of the baby boom was that women were entering the workforce in larger numbers, that the economy was capable of absorbing them, and that preventing births by contraception, sterilization, or abortion had become easier. This situation was to be one of some permanence.”13 On that last point, by the mid-1950s contraception was almost universal, close to 80% of m...