![]()

1

LLOYD L. BROWN: BLACK FIRE IN THE COLD WAR

The trouble with Negro literature, far from being the alleged “preoccupation” with Negro material, is that it has not been Negro enough.

—LLOYD BROWN, “WHICH WAY FOR THE NEGRO WRITER?”

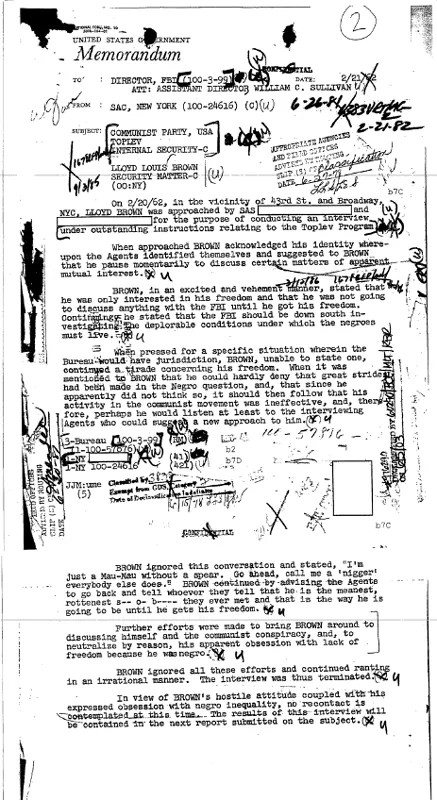

ON FEBRUARY 20, 1962, in the vicinity of Forty-Third Street and Broadway in Manhattan, two FBI special agents approached the activist and writer Lloyd Brown, seeking his cooperation in their investigation of communist writers and artists. According to one of the entries in Brown’s extensive Freedom of Information file, the agents identified themselves and asked if they could discuss “certain matters of apparent mutual interest” about the “communist conspiracy.” By this time the openly communist Brown had become outraged by the attempts of the FBI to interview him and stated that he was not going to discuss anything with the FBI until he, along with the rest of the Negro race, got his freedom. He told the agents that they should be down South investigating “the deplorable conditions under which negroes [sic] must live.” In their report of Brown’s response, the agents described what must have seemed to them like a strangely incongruous reaction:

BROWN ignored this conversation and stated, “I’m just a Mau-Mau without a spear. Go ahead, call me a ‘nigger’ everybody else does.” BROWN continued by advising the Agents to go back and tell whoever they tell that he is the meanest, rottenest s-o-b they ever met and that is the way he is going to be until he gets his freedom. [The report concluded:] In view of BROWN’s hostile attitude coupled with his expressed obsession with negro inequality, no recontact is contemplated at this time.

(U.S. FBI, Lloyd Brown, 100-24616, 2-21-62; emphasis added)

FIGURE 1.1. Page from Lloyd L. Brown’s FOIA file (1962).

Source: U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation.

This encounter with the FBI agents, who continued to trail him for years even after he was no longer associated with the Communist Party, was typical. In all FBI attempts to interview him, he was “hostile and uncooperative,” and, though they continued to hound him at work, in the streets, and at his New York co-op, they eventually concluded that further contact would not be contemplated because “he was firm in his refusal to cooperate in any way” (U.S. FBI, Lloyd Brown, 2-23-67). Besides Brown’s fearlessness before government spies, the incident is a remarkable for another reason. It dramatizes the emphasis in Brown’s work and life on the relationship between racial injustice and political radicalism. Ten years earlier in 1951, when he published his first novel Iron City with the Marxist press Masses & Mainstream, it was so blatantly procommunist that Dalton Trumbo, one of the famously blacklisted Hollywood Ten, said that publishing that book during the Cold War was like setting a match to kerosene. For Brown, however, the novel’s radicalism was not only in its normalization of communists but in its challenge to 1950s neoconservatism, which urged black writers to abandon race matters, racial themes, and social protest. In the same year as Iron City, Brown published his manifesto on black literature, also in Masses & Mainstream. The two-part essay “Which Way for the Negro Writer?” also argues vehemently for black writers to resist conservative attempts to mainstream black writing and eliminate racial protest. Brown published at least twenty-four essays and reviews in Masses & Mainstream, covering every aspect of black culture from jazz to civil rights to racism in psychoanalysis.1 Between 1948 and 1952, as the journal’s editor, he reviewed nearly every major book written by a black writer, including Chester Himes’s Lonely Crusade (1947), Saunders Redding’s Stranger and Alone (1950), William Demby’s Beetlecreek (1950), Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952), and Richard Wright’s The Outsider (1953). Strangely for such a prolific and observant reviewer, Brown never wrote about Gwendolyn Brooks’s 1950s publications, even though her writing is easily as politically radical as his. In his reviews Brown continually castigated black writers for what he considered their “contempt for the working class,” their “Red-baiting,” and their focus on pathology in black culture. During his tenure in the 1950s as an editor at Masses & Mainstream, that journal published more articles by and about black writers than any other journal except for black ones, bragging in their 1952 Black History Month issue about the number of black writers in their pages.2 Brown even shows up in the correspondence of two of his public antagonists, Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray, though, quite unexpectedly, they found themselves on his side.3 Brown might very well have claimed the taunt he threw at his FBI investigators as the signature of his life and work: he was indeed a Mau Mau rebel, not with a spear but with his pen.

Brown was such a ubiquitous presence in literary, cultural, and political circles in the 1950s that it is hard to account for his absence from contemporary black literary history on grounds other than his left-wing politics. In my correspondence with Brown, dating from 1996 until his death in 2003, his letters describe close friendships with Langston Hughes, Alice Childress, Paul Robeson, W. E. B. Du Bois, and the Freedomways editor Esther Jackson—leftists all, but also, like Brown, often excised from the main currents in the African American and American literature and culture they actually helped create. Brown’s literary friendships and collaborations, which are important records of African American literary history, have almost never been documented.4

Throughout the 1950s, Brown worked closely with Paul Robeson on the newspaper Freedom, reputedly ghostwriting many of the columns attributed to Robeson. He was also something of a ghost in Langston Hughes’s life. He made a special effort to support Hughes when Hughes was under attack by Senator McCarthy’s investigative committee, writing a rebuttal to a negative review of Hughes’s work by James Baldwin in the New York Times (Brown 1959), but he always kept their “underground friendship” off the record so as not to conflict with Hughes’s precarious peace with Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). When Iron City was published, Hughes telephoned to say how much he liked it and that he was sure that ten years earlier it would have been a Book-of-the-Month selection. Hughes never wrote anything about the novel publicly, though he felt that Iron City’s character Henry Faulcon and Brown’s own Jesse B. Simple were close kin. In 1959, when Hughes’s Selected Poetry was published, Hughes phoned Brown to say that he wished he could dedicate the book to him. Instead he sent a copy with this private dedication on the flyleaf: “Especially for Lloyd Brown—these 30 years (+) of poetry—Sincerely, Langston Hughes.”5 Brown’s procommunist politics have made it easy for critics to dismiss him. He is almost totally absent from contemporary versions of African American literary history, never cited as an influential ancestor, his writings nearly always dismissed as communist propaganda.6 But I make special mention of these ghostlike appearances of Lloyd Brown in African American literary circles to establish that in the 1950s, even as a spectral presence, he managed to play a major role in black cultural production.

This chapter seeks to reestablish Brown’s significance as both novelist and cultural critic and to show that CP aesthetics were, for him as for many radical leftists, ultimately more liberating than limiting. Writing from the Left, outside of the confines of the Jim Crow literary and cultural establishments, and with the institutional and creative support of the Party, Brown had the freedom to reject mainstream literary mandates that tried to restrict representations of black subjectivity. In direct opposition to the assimilationist rhetoric of the integration period, left-wing activists and artists like Brown challenged the very structures that defined the limits of integration, exposing the terms of analysis that made black writers into the “Other” and black writing into “The Problem.” In his powerful and almost totally unknown 1951 essay-manifesto “Which Way for the Negro Writer?” he insisted that the crusade of the black neocons in the 1950s to unblack the Negro in literature and to aim for acceptance in the mainstream was not simply an aesthetic agenda but a response to Cold War manipulations that exerted as much ideological pressure on these writers as some claimed the Communist Party had on its members.

While the canonical black texts of the 1940s and 1950s—Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, J. Saunders Redding’s Stranger and Alone, Chester Himes’s Lonely Crusade, and Willard Motley’s We Fished All Night—portray the Party as a deceptive and manipulative organization using the Negro for its own opportunistic ends, Brown portrayed his communist characters as positive forces in their communities. Brown also had Richard Wright and Bigger Thomas in mind when he wrote Iron City. The three politically informed working-class intellectuals—Faulcon, Zachary, and Harper, and the working-class Lonnie James—the collective protagonists of Iron City—were deliberately fashioned in opposition to the murderous, illiterate Bigger Thomas and meant to stand as the more representative black proletariat of the 1940s.7 By putting Lloyd Brown’s Iron City in dialogue with Richard Wright’s Native Son, I show how the focus on Wright as the major figure on the Left distorts and minimizes the political and aesthetic value of communist influence on black literary production. In contrast to Wright, Brown embraced formal experimentation, fashioning Iron City out of the materials of leftist culture—documentary texts, 1930s proletarian drama, black folk culture, and even surrealism. Precisely because Brown remained faithful to the Communist Party and objected so publicly and articulately to any retreat from politically engaged art, he compels us to question those erasures that enabled this highly political decade in U.S. history to become depoliticized in contemporary African American literary and cultural histories.

LLOYD BROWN IN BLACK AND LEFTIST CULTURAL CIRCLES: “WHICH WAY FOR THE NEGRO WRITER?”

While Brown may have been ignored and marginalized by post-1950s literary critics, as editor and writer for New Masses between 1947 and 1953, he was a known quantity in the 1950s black and left-wing literary world. Between 1947 and 1954, Brown published more than twenty-five articles and reviews covering black literature, civil rights, race, and international issues.8 But it was his critique of the Atlanta University–published black cultural journal Phylon that put him in the crosshairs of the 1950s black literary establishment. In the winter of 1950, Brown read the literary symposium that appeared in the December issue of Phylon, which contained one respondent after another suggesting that fiction featuring racial issues, black characters, or black settings could not be “universal.” For Brown the symposium was a rejection of blackness in exchange for the promises of integration: “It was a challenge to everything I believed in. It was as though they were trying to wipe us out. I’m all for integration, but only if it’s on the basis of equality.”9 The Phylon editors had sent out a questionnaire to twenty-three prominent black writers and academics, asking them to respond to several—clearly leading—questions:

(1) Are there any aspects of the life of the Negro in America which seem deserving of franker, or deeper, or more objective treatment? (2) Does current literature by and about Negroes seem more or less propagandistic than before? (3) Would you agree with those who feel that the Negro writer, the Negro as subject, and the Negro critic and scholar are moving toward an “unlabeled” future in which they will be measured without regard to racial origin and conditioning?

(Atlanta University and Clark Atlanta University 1950)

Questions one and two were throwaways; what the Phylon editors most wanted to hear about was that “unlabeled future,” which they believed would usher in the racial millennium.

In what the editors called “a mid-century assessment of black literature,” Phylon devoted a special issue to the responses of twenty-three writers and educators to the questionnaire. The most well known were Gwendolyn Brooks, Hugh Gloster, Arna Bontemps, Langston Hughes, Robert Hayden, Alain Locke, Margaret Walker, George Schuyler, Sterling Brown, William Gardner Smith, and J. Saunders Redding. The most prominent absent voices included four well-known leftists: Ernest Kaiser, W. E. B. Du Bois, Ralph Ellison, and Paul Robeson; the one excommunist Richard Wright; and the communists Lloyd Brown and Abner Berry. Twelve of the twenty-three that were included were college professors, eleven of them on the faculty of major black universities. Ira De A. Reid, the chair of the Department of Social Science at Haverford College, was the only black professor at a predominantly white school. The symposium responses range from the archconservatism of Gloster, a professor at Hampton Institute, to Walker’s subtle left-wing radicalism, to a postmodernist poem by Hayden that critiqued the racial essentializing of the symposium.10 The conservative voices in this issue are worth special attention because they were in the ascendancy in the early 1950s and because they became the grounds for Brown’s attack.

Picking up on the direction of the third question, Gloster said unequivocally that the focus on “racial subject matter” had handicapped the Negro writer, retarded his “cosmic grasp of varied experiences,” diminished his philosophical perspective, and lured him into “cultural segregation.” He praised writers like Richard Wright for transcending the color line by identifying Bigger Thomas with “underprivileged youth of other lands and races,” and he heralded Zora Neale Hurston and Ann Petry for producing novels with no black characters. Like many of the respondents, Gloster singled out Willard Motley for his 1947 novel Knock on Any Door, about an Italian youth, which, he said, “[lifts] his work to the universal plane by representing humanity through an Italian boy.” As if gender somehow transcended race, Gloster praised Gwendolyn Brooks and Petry for dealing with women’s issues, which he said are not racial matters, since they deal with such womanly concerns as “passion, marriage, motherhood, and disillusionment in the lives of contemporary Negro women.”

Other respondents followed in Gloster’s footsteps, cautioning black writers to free themselves from their “racial chains” by not writing about black characters. The novelist and critic J. Saunders Redding urged the Negro writer to register “human” rather than “racial” values by “testing them in creatures of his own imagination who were not Negro.” Charles Nichols of Hampton Institute saw a “heartening maturity” in writers who were “not primarily concerned with Negro life” and predicted that the Negro writer was in the process of coming of age “though, happily, not as a Negro.” Even Langston Hughes, whose entire literary output could be described as culturally black, found it a “most heartening thing to see Negroes writing in the general American field, rather than dwelling on Negro themes solely,” and he too praised Willard Motley, Frank Yerby, Ann Petry, and Dorothy West for presenting “non-Negro subjects” and thereby lifting their work to a “universal plane.”

In his symposium essay, Alain Locke, the “dean” of African American letters, deployed the term “universal” eleven times, admonishing writers to achieve a “universalized particularity,” to find a way to write about race “from the universal point of view,” to write of racial life but to consider it from “the third dimension of universalized common-denominator humanity.” Full of obfuscating terms and what seems like sheer terror over being left off the “universal” bandwagon, Locke’s essay ends with the declaration that “outer tyrannies” like segregation, prejudice, racism, and the exclusion of black writers from the mainstream of American literature and publishing are so much a part of the past that they no longer pose a serious problem for the black writer. Abandoning his left-leaning politics of the 1930s, Locke insisted that the only things restricting black writers were “inner tyrannies”—“conventionality, repressions, and fears of race disloyalty.”11

A telling sign of Cold War pressures and anxieties is that the symposium respondents reproduce, almost verbatim, the official State Department line that racism was “a fast-disappearing aberration, capable of being overcome by talented and motivated individuals.” The journalist Era Bell Thompson wrote that integration and full equality for blacks were so close at hand that writing about Jim Crow racism should be discarded as a relic of the past. White editors, she claimed, are only interested “in the quality of a writer’s work, not in the color of the skin, and black writers need only be ready to take advantage of these opportunities.” “White journalism,” she continued, apparently unaware of the irony of the term, “has always been open to the Negro, but never to the extent that it is today.” N. P. Tillman of Morehouse College agreed with Thompson that there was no bias in the book business: “The American reading public accepts a book by a Negro now on much the same basis as it receives a book by a white author.” The Fisk University professor Blyden Jackson wrote with blithe optimism, “All around the air resounds with calls to integrate the Negro into our national life.” Later, the poet Sterling Brown (1951, 46) would write that the Phylon group had turned integration into a “literary passing for white.”

Bear in mind that these calls from the symposium contributors to erase blackness and discover the “universal” subject are not signs of a postmodernist move toward hybridity and multiple subject identities. By minimizing racial identity and racial strife and promoting the image of a democratic and racially progressive United States, the Phylon group was offering race invisibility as a bargaining chip for American citizenship status. As Ernest Kaiser, one of the left-wing writers absent from the symposium, notes in a letter to me, the Phylon group was “moving quickly to establish its non-left credentials [in order to] maintain its financial support from the mainstream”:

You understand that the magazine doesn’t want to embarrass the College and lose its subsidy. By 1948, the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, was attacking Du Bois and Robeson. Almost all middle class black persons were becoming anti-Communist in order to save their careers. The writers who contributed to the Phylon symposium are all college professors who...