![]()

1

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF SERA KHANDRO

I, this inferior woman, will tell you a bit about my circumstances—

from the time I was seven, ḍākinīs took care of me;

they reassured me in reality, in visions, and in dreams.

From the time I was eleven, the Master Accomplished Awareness Holder

Saraha took care of me and bestowed ripening [empowerments] and liberating [instructions] upon me.

When I reached the age of twelve, I obtained the genuine prophetic guide of the Ḍākinīs’ Oral Transmission Profound Treasure.

From the time I was thirteen, I exerted myself only in benefiting others.

At fourteen, in accordance with the ḍākinī’s command, I came eastward

to the land of eastern Tibet, which is like the demons’ island.1

Not dying, while living I experienced the suffering of hell.2

The hell on earth Sera Khandro spoke of in a visionary interaction with the paramount female saint of Tibet, Yeshé Tsogyel, began amid the nobility of late nineteenth-century Lhasa and continued among the nomads in the grasslands of Golok in eastern Tibet. Lhasa during Sera Khandro’s childhood was the cosmopolitan center of Tibetan political and cultural life on the edge of the Qing dynasty. This urban context could hardly have been more different than the vast pasturelands and snow peaks of Golok and Serta that later became her home. Located at the crossroads of the eastern Tibetan regions of Amdo and Kham that today form the western parts of Sichuan and Qinghai provinces, the majority of the Golok and Serta territories were independent confederations controlled neither by the Dalai Lama’s Tibetan government nor by the Chinese authorities during Sera Khandro’s time there from 1907 to 1940. The narrative Sera Khandro weaves over hundreds of manuscript pages provides a rare account of life in a wealthy noble family in Lhasa in the early twentieth century, then escape and entry into the closed ranks of religious hierarchy in Serta and Golok, and finally renown throughout the eastern Tibetan highlands as a Treasure revealer (gter ston) and a ḍākinī incarnation of Yeshé Tsogyel. The present chapter concentrates on her description of everyday life in this world from 1892 to 1940 in its historical context. Reserved for further analysis in later chapters are questions about style, voice, topos, and literary influences within Sera Khandro’s auto/biographical writings. Here the focus is on the narrative sequence of events in Sera Khandro’s life as she portrayed it, replete with a magical realist-like flavor in which the ordinary and extraordinary overlap.

In the late 1920s, while Sera Khandro was writing the long autobiography examined in this book, she also wrote a condensed autobiography in verse summarizing the main contours of her life.3 In this short version, she divided her life into five different phases: 1) her religious aspirations and obstacles during her childhood in Lhasa from birth through age twelve; 2) the difficulties of her departure from Lhasa and entry into Golok from age thirteen through seventeen; 3) her life as Gyelsé’s spouse at Benak Monastery in Golok from age eighteen through twenty-seven; 4) her reunion with her root lama, Drimé Özer, from age twenty-eight through thirty-one; and 5) her life afterward based at Sera Monastery in Serta, from age thirty-two on. This chapter follows the general structure of Sera Khandro’s delineation of these phases of her life. It concludes with a summary of the eyewitness account of her last years and her death written by her close attendant and scribe, Tsültrim Dorjé, as well as a later rendition of her last years written by her disciple Jadrel Sangyé Dorjé Rinpoché.

LHASA TWENTIETH AT THE TURN CENTURY OF THE

The Lhasa into which Sera Khandro was born in 1892 was a vibrant religious, political, and commercial center within Asia. In the words of L. Austine Waddell, a British explorer who toured the city as a member of Sir Francis Younghusband’s infamous 1904 invasion of Tibet, Lhasa was “the pivot of the world of High Asia,” a Mecca of religious devotion as well as international trade.4 At this time central Tibet was part of the Manchu-controlled Qing dynasty (1644–1911), although Qing sovereignty in Tibet was in decline. While the Qing government was focused on affairs farther east, such as the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95 and the Boxer Rebellion of 1898–1901, the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Gyelwa Tupten Gyatso (1876–1933), assumed power in 1895.

Sera Khandro never mentions encountering any Caucasians in her autobiography, nor does she allude to the British invasion of Tibet that forcibly entered Lhasa in 1904. But several of the soldiers, journalists, explorers, and spies who found their way there at the turn of the twentieth century left detailed field notes about what they discovered about the Lhasa in which Sera Khandro grew up. In the words of the Indian national and British spy Sarat Chandra Das, who journeyed to Lhasa in 1881–82:

It was a superb site, the likes of which I have never seen. On our left was the Potala with its lofty buildings and gilt roofs; before us surrounded by a green meadow, lay the town with its tower-like, whitewashed houses and Chinese buildings with roofs of blue glazed tiles.5

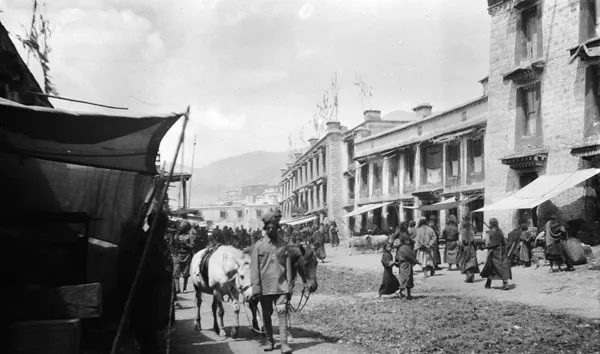

The Buriat Russian explorer G. Tsybikoff, who visited Lhasa in 1900, remarked that “the gilt roofs of the two principal temples glisten in the sun and the white walls of the many storied buildings shine among the green tops of the trees.”6 Tsybikoff reported that the city was surrounded by orchards and trees, which a few years later the British journalist Edmund Candler, who also accompanied the Younghusband expedition, described as “willow groves intersected by clear-running streams, walled-in parks with palaces and fish-ponds, marshes where the wild-duck flaunt their security, and ripe barley-fields stretching away to the hills.”7 Inside Lhasa’s green circumference, Waddell recorded that

The compact town is barely half a mile square. Its streets are rather narrow and neither drained, nor paved, nor metalled, but the main ones are laid out on a fairly good plan. The houses are substantially built of stone walls two to three storeys high, with flat roofs (none sloping) and carefully white-washed, the beams of the eaves being often elaborately picked out in red, brown and blue.8

The multistoried whitewashed houses of Lhasa were built to last, with solid walls punctuated by windows without glass panes, hung with cotton curtains or protected from the winter chill with oiled Tibetan paper.9 Mitigating their fortresslike quality were occasional birdcages hanging from windows that sheltered singing birds, larks, and doves as well as rows of flowerpots brightening the windowsills and bordering the entrance walls.10 These houses lined wide, unpaved roads and narrow lanes interspersed with tall poles strung with prayer flags and numerous incense kilns.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Lhasa’s streets saw no wheeled traffic whatsoever, but there was a steady stream of Tibetan townspeople, pilgrims, and traders from far afield as well as numbers of Mongolian, Manchu, Chinese, and central and South Asian city residents.11 Lhasa’s permanent lay population consisted of about 10,000 residents, the majority of whom were women, with a monastic population of about 20,000 men who lived in the three largest monasteries outside the city: Ganden, Drepung, and Sera. Out of the Lhasa population, in 1904 the Nepalese Consul in Lhasa estimated that 7,000 were Tibetans; 2,000 were Chinese and half Chinese-Tibetan traders, military, and police; 800 were Nepalese merchants and artisans; 200 were Muslim traders from Ladakh and western China; 50 were traders from Mongolia, and 50 were traders from Bhutan.12 Many visitors were drawn to Lhasa for its position as Tibet’s political and religious center as well as its brisk markets. Tibetan, Chinese, Nepalese, Kashmiri, and Bhutanese shops lined the streets, encircling the main market area in the great square before the seventh-century Jokhang Temple. Waddell describes the articles on display in street stalls outside the shops in 1904 as “chiefly native eatables, trinkets, drugs, books, clothes, and broadcloth.”13 Perhaps among those books for sale were both Tibetan-language works and Chinese-language literature that circulated throughout the Qing dynasty, though foreign accounts do not specify. The many Chinese shops sold primarily bricks of tea, Tibetans’ beverage of choice, as well as silk and cotton fabrics, wooden furniture, and ceramics. Nepalese merchants’ stock included cloth, drugs, brass bowls, and lamps, while Kashmiris sold spices and dried fruits including persimmons, cooking peaches, crabapples, mulberries, gooseberries, and red currants.14 Various specialty items of British design imported from India by Bhutanese, Nepalese, Kashmiri, and Chinese merchants were also becoming fashionable in Lhasa at the turn of the century, including mirrors, beads, jars, matches, penknives, cloth, enameled vessels, teapots, plates, and cups.15 Waddell even found two quart bottles of English Bulldog stout at six shillings a bottle and was told that wealthy Tibetans enjoyed it as a liqueur.16 In return for all these foreign delicacies, Tibetans sold and exported animal furs of many varieties, yak tails, sheep’s wool, borax, salt, silver, gold, yaks, horses, and mules. Though not sold in the Lhasa markets because of their sacred status, Buddhist ritual implements, statues, and scriptures were exported to Mongolia.17 Much of this trade took place by barter, bricks of tea being a convenient form of currency, but Lhasa’s international flavor came through in the plethora of monies in use in the early 1900s, including coins minted by the Tibetan government in Lhasa, Indian rupees, Russian rubles, and Chinese coins and silver ingots.18

FIG. 1.1 Lhasa street scene, photograph taken by F. M. Bailey on the Younghusband Mission to Tibet, 1903–4

© THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, NEG. 1083/14 (428 RECTO)

LHASA BIRTH AND CHILDHOOD

This dynamic multicultural context of early twentieth-century Lhasa emerges through Sera Khandro’s description of her birth and its aftermath:

First, regarding how I was born, north of Bodhgaya, India, is the seat of the supremely noble incarnation of Avalokiteśvara, the Dharma King Songtsen Gampo. In this eastern part of Tibet, the Land of Snow, west of the Rasatrül Temple [the Jokhang Temple], there is a place called Lumotil (klu mo mthil), whose earth guardian is Dorjé Yudrönma. Near the location of various amazing statues, including the main statue of the land, the Jowo Śākyamuni, there was an estate more sublime than all the others named Gyaragashar (rgya ra ga shar). Inside lived Prince (lha sras) Jampa Gönpo, a ruler endowed with power, wealth, and stability who belonged to a royal Mongolian lineage named “pure divine lineage” (dkar po lha yi rigs). Renowned as an incarnation of Rongtsa,19 he was empowered in mind Treasures and manifested marks of accomplishment and so forth without difficulty. He lived as a householder in accordance with the following prophecy from the Nechung Dharma Protector:

Dress as a ngakpa.20 Since the Lady of the Nup clan named Tsering Chöndzom is from a ḍākinī lineage, if you marry her siddhas and yoginīs will be born in your household again and again.

Since all his neighbors and relatives told him to do this, he married Tsering Chöndzom and adhered to the tradition of his forefathers.

I took birth in a family of “royal divine lineage” (mi dbang lha yi rigs) that was respected and venerated by all people, high and low. On the first day of the first month of the water dragon year [1892], my mother gave birth to me without pain. The baby was unlike others, born in an egg.21 Not daring to touch me, Mother told my father the story.

When she did, Father said, “An excellent sign.”

As he opened the egg with a feathered arrow ornamented with five colors of silk, rainbow light gathered, vultures danced above the house, a pleasant aroma pervaded the area, and more. Since the sound of a conch trumpet filled the house, both Mother and Father said, “We thought this baby was an incarnation, but she isn’t. Why does this girl have these special signs?”

All the neighbors said, “An amazing incarnation was born in the leader’s family!”

Then they called a Brahmin, and after he washed the baby’s body with perfumed water and looked at her marks, he said, “It is appropriate for her to be an awareness woman22 who is an accomplished one adhering to Secret Mantra. Living as a householder will be extremely bad for her. But she is also not to be a shaven-headed nun. Her hair shows signs of being blessed.”

My father, mother, and relatives announced that on my body there were letters and that my hair showed signs of being blessed by ḍākinīs and in particular, that “baṃ,” “ha,” “ri,” “ni,” and “sa” were written on my five cakras. Everyone rejoiced and held a grand celebration feast for my birth.

Then, saying that I needed to be given a name, the Chinese group (rgya sde rnams) said, “She should be given our year as her birth year. Since there were two 30th days, she was born in the hare year [1891].”

The Tibetan faction (bod shog pa rnams) said, “Since she was born on the first day of the Tibetan year, she was born in the dragon year [1892].”

Since the Chinese and Tibetans were not in agreement about giving me a name, they asked Taklung Mahā Rinpoché to proclaim my name. He gave me the name Kelzang Drönma.

The Brahmin said, “You all, the Chinese group and the Tibetan group, don’t quarrel with each other! Since this girl with unusual marks is amazing, it seems she won’t be our female leader. We must use the name that Mahā Rinpoché gave her.” But everyone was displeased.

Mot...