![]()

part 1. militant acts

![]()

1 The Red Decade and Its Cultural Fallout

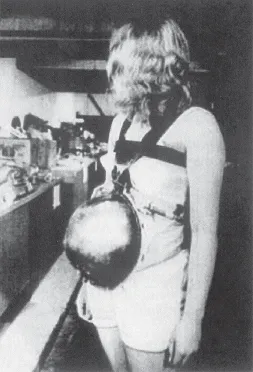

In 1971, when the Red Army Faction was just over a year old, the members Holger Meins and Jan-Carl Raspe began to make a film about liberation movements and world politics. They sought out Dierk Hoff, a sculptor and welder with ties to Frankfurt’s leftist circles, and asked him to design props for the project: fake hand grenades, pretend pipe bombs, and the like. The film was going to be a Revolutionsfiktion, a tale of insurgency that would awaken its viewers to the international struggle of the urban guerrilla. This job led to further collaboration, including Hoff’s fabrication of a “baby bomb”: an explosive undergarment fashioned to resemble a pregnant woman’s expanding middle. There is no record of a RAF member infiltrating public space while wearing the bomb, nor is there any of its detonation.1 But a photograph remains. In it, the bulbous, metal device is strapped onto a young woman’s torso. Loose hair obscures her face, but the pointed cups of her white brassiere are clearly visible. The picture, like the baby bomb itself, made it clear that the Far Left had taken the technology of gender into its arsenal and that it was just waiting for the right moment to use it.

We know that scores of real bombs were deployed in the campaign that the RAF led from 1970 to 1998. In May 1972, for example, the group executed lethal attacks on the U.S. army’s Frankfurt Headquarters and its Supreme European Command in Heidelberg, killing four American officers. The RAF defined itself as an antifascist, anti-imperialist organization engaged in revolutionary violence against capitalism. After the government of the Federal Republic (and the administrations of West Berlin, which, at that point, was an affiliated exclave), the United States and NATO were its prime targets. It is believed that some of Dierk Hoff’s explosives were used in these actions. Hoff disavowed his link to Meins and Raspe shortly thereafter, when the two were arrested together with Andreas Baader, but his small part in the RAF story discloses a truth about the German armed struggle: the force of leftist violence quickly eclipsed the RAF’s subversive intent. Their militancy was always symbolic, but it was also always brutally real.

Klaus Benz, Babybombe (Babybomb), 1976. Published in Der Spiegel 6 (Feburary 2, 1976).

What was the Red Army Faction and which conditions gave rise to it? This chapter outlines the history of the RAF’s emergence and lays the groundwork for an attenuated analysis of postmilitant culture in Germany. It begins with a description of the German Autumn of 1977—the two months when Baader-Meinhof machinations brought West Germany to a state of emergency. The scope then widens to include the social and political shifts that first prefigured this season and later followed upon it. Especially in the “red decade” that led up to the crises of 1977, the German Left underwent a series of reinventions, ruptures, and realignments.2 The RAF was one product of these breaks, but the group wasn’t the singular culmination of the “cultural revolution,” as the historian Gerd Koenen has termed it, that overtook much of the FRG in the middle years of the Cold War. Indeed the RAF’s actions—and the artistic response to them—can only really be assessed within the larger context of these transformations.

After the siege of National Socialism, Germans from both sides of the country endeavored to build new institutions of democracy. Courts, workplaces, and schools became sites of reconstruction and contestation. The German Left was at the forefront of this critique; two of its constituent groups, critical theorists and feminists, were also the first to perceive the incipient threat of postwar militancy. Their wide-ranging debates about the Far Left offer crucial insights into both RAF militancy and the art and literature that have come After it.

Just as these intersecting historical and conceptual currents provide an important context within which to read the unfolding of the German Autumn, a pair of artworks can be identified as foundational for postmilitant culture and its interpretation. They are the film Deutschland im Herbst (Germany in Autumn), released right After the events of 1977, and Gerhard Richter’s cycle of paintings 18. Oktober 1977 (October 18, 1977), which was completed and first exhibited ten years later, in 1988. Both works reflect upon the difficulty of laying to rest what Klaus Theweleit has called “the specters of the RAF,” and both detect the sexual politics that stirred within the armed struggle.3 As we shall see, Germany in Autumn articulates the social questions that shaped leftist agendas in the 1970s, even as it conveys the anxiety and despair that beset so many when the RAF took its suicidal dive. October 18, 1977 stands at a remove from the conflicts of revolutionary force. Richter foregrounds the aesthetic practice of painting, blurring the margins between document and memory. His choices of subject matter, composition, and technique have become a central reference point for much of the postmilitant culture that has appeared in the decades since he first exhibited the series.

How can a picture or a text take stock of social change, of terrorism, or of symbolic violence? Revisiting Germany’s years of postwar dissent and differentiation, we establish a platform from which to evaluate the capacity of art and literature to represent these phenomena. The long and divergent trajectories of postmilitancy were set by several factors: modern German history, artists’ and writers’ first confrontations with the subject of the RAF, and the proliferation of commentary and scholarship on the significance of militancy and terrorism. The next sections introduce these factors and show how they variously come together and move apart.

1977: The German Autumn

The German Autumn began in early September 1977, when a RAF cell kidnapped Hanns-Martin Schleyer, a former Schutzstaffel (SS) officer and member of the Nazi Party. Although he was interned as a prisoner of war from 1945 to 1948, Schleyer was not punished for his complicity with the Hitler regime. He returned to West German society as a civil servant, worked his way up in the Daimler Benz Corporation during the years of economic recovery, and eventually became the president of the influential Federation of German Industries and the Confederation of German Employers’ Associations. He was slated to serve as Chairman of the World Economic Forum at Davos. To many on the Left, Schleyer was the picture of evil, living proof that the Bundesrepublik had not fully broken with the fascist strains of the Third Reich.

Schleyer’s abduction was preceded by a string of militant and criminal acts. Over the course of seven years, the RAF had used nearly every guerrilla tactic—bombings, robberies, assassinations—in an attempt to make the FRG and its people confront the nation’s legacy of authoritarianism and to resist its integration into NATO’s military industrial complex. Along with these tactics, the RAF exploited opportunities for publicity. In the Schleyer kidnapping, the group videotaped scripted declarations from their hostage, in which he confessed his guilt in Nazi crimes and asked for the release of RAF leaders who were serving life sentences for murder and terrorist conspiracy at the infamous Stammheim Prison. The footage was aired around the world, but when federal authorities refused to negotiate with the terrorists, tensions escalated.

On October 13 a commando of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) hijacked a Lufthansa aircraft with ninety-one passengers and crew, abducting their flight from Mallorca, across the Mediterranean, and into Eastern Africa.4 Their demand: the discharge of RAF members, whom they considered their comrades in the global anti-imperialist struggle. The hijackers (two women, two men) killed one of the pilots, and the standoff was covered by media agencies around the world. Germans sat riveted to their television sets as Chancellor Helmut Schmidt tried to control the damage. They were conjoined as a national audience for one of the first times since the radio broadcasts of the Nazi period. In the early 1970s, the government began unrolling a program to curtail the Far Left that extended deeply into civil society; it included employment restrictions for suspected radicals, wiretapping, and random house searches. As the German Autumn approached its peak, the shocked public further relinquished even more of their constitutional rights. At the same time, the government imposed a news blackout for extended periods of the Schleyer abduction. Rigorously reported papers scaled back coverage, while the tabloid press capitalized on the explosive stories and images.

On October 17, 1977, almost five days After the high-stakes odyssey had begun, the Grenzschutzgruppe 9 (GSG-9), a West German counterterrorism unit, together with special task forces from Somalia and Interpol, stormed the Lufthansa plane while it was parked at the Mogadishu Airport. Three of the four hijackers were killed in the barrage, but all ninety of the remaining passengers and crew were rescued. When the news broke, the Stammheim prisoners made the final play of their endgame: following a pact, three committed suicide, two by gunshot, one by hanging.5 They styled their deaths to look like murders, but these acts had the effect of a timed-release suicide bomb—one with repercussions that would last for decades.6 The next day Schleyer’s body was found dead in Alsace-Lorraine, just over the French-German border; RAF members called the German Press Agency and claimed responsibility for the shooting. The second and third generations of the RAF remained at large, but Germany’s most violent phase of leftist terror was ending. The crises of the German Autumn forced Schmidt and his cabinet into a deadly predicament. Many cite their management of the situation as an inaugural act of West German democracy; others concede that the draconian measures taken to control domestic militancy nearly proved the RAF right: the restrictions of civil liberties disclosed the government’s will toward domination and undermined the ethical principles of the Rechtsstaat.7 As the political scientist Herfried Münkler has argued, the asymmetry of the German Autumn—left-wing provocation versus the state of exception invoked by federal powers—prefigured the political conflicts that are part of our current global reality.8

Germany’s spell of leftist militancy and terror was preceded by a long “spring” and “summer” of social and political activism. In the 1950s thousands took to the streets across Western and Eastern Germany and demonstrated against both the rearmament of the Bundeswehr and American military interventions in Korea and Southeast Asia. As ideological contests between the United States and the Soviet Union inscribed deep divisions between the FRG and the GDR, a vibrant New Left movement emerged in the West. The New Left’s ideals of world peace were based on socialist principles, but they departed from the labor-based agendas of hard-line communism. Together with the antiwar and antinuclear Bürgerinitiativen, other social movements, particularly feminism and environmentalism, added momentum to the New Left.9 Moving into the 1960s, as the West German economy prospered and the nation entered a new phase of stability, their struggles for social justice made real headway. But dissent among the widening circles of left-oriented West Germans brought about new alignments. The Socialist Student Union (Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund, or SDS) was excluded from the Social Democratic Party in 1961. Together with other activists, they formed the Extraparliamentary Opposition (Außerparlamentarische Opposition, or APO); by the mid-1960s they had a plan to “march” their radical critique through the nation’s institutions. Looking abroad, young people were galvanized by images and reports of the fights for decolonization and civil rights in Africa, Latin America, and the United States.10 In West Germany, too, a new reality seemed just around the corner.

The Red Decade: 1967–1977

Germans were particularly attuned to the situation in Southeast Asia. In 1965, before many antiwar protests had been waged in the United States, West German leftists organized a series of speak-outs and demonstrations about the political conflicts in Indo-China.11 Some saw significant parallels between the FRG and South Vietnam: the U.S. military occupied both countries and sought to manage the two “subaltern” governments to its own advantage. Even those who would not acknowledge such a reductive equivalence between the two situations still felt moved to speak out against the U.S. invasion of Southeast Asia. The first Germans to come of age After World War II considered themselves especially obligated to resist all forces of domination. While most took up a pacifist critique of the American occupation, more radical factions adopted violent tactics. Those who would form the RAF moved toward the cutting edge of this formation, but the group’s not-so-distant origins pointed back to the center of the postwar Left.

The Vietnam War evoked several associations for Germans. In his comparative analysis of leftist militancy in the United States and West Germany, the historian Jeremy Varon argues that Vietnam was doubly “coded” for young Germans: they condemned the American military deployment “both in its own right,” Varon stresses, “and insofar as it recalled Nazi violence.”12 Ulrike Meinhof also saw a parallel between U.S. bombings over North Vietnam and Allied air wars over Dresden in 1945: both, she wrote, were war crimes.13 Recently, looking back at the 1960s and 1970s, Birgit Hogefeld, a member of the RAF’s third generation, noted that the analogies between the media images of the Vietnam War and Allied film footage of German death camps could not be ignored. For her and many others, it was “absolutely imperative to take responsibility and to take action.”14 No one needed to rely on these comparisons in order to oppose the conflict, but the memory of German fascism made the geopolitics of the Cold War intolerable. Radicalized protesters sought to sharpen the contradictions they perceived in their society. They wanted to tempt the German state to react with its full force, and to unmask the violence that subtended its foundations. This, they thought, would generate a revolutionary situation, one that the public could not ignore.

The founding moment of the RAF was conceived and executed by Meinhof. Long active in New Left circles of media and culture, she had taken an interest in the situation of Andreas Baader, publishing articles that commented on (and in some cases validated) his criminal career of auto theft, arson, and other, more pointedly anarchic activities. In the spring of 1970, Berlin authorities caught Baader on the lam and remanded him to a local prison, where he was sentenced to serve out a long prison term for planting bombs in two Frankfurt department stores, an action he had pulled off with Gudrun Ensslin. Meinhof orchestrated a scheme in which Baader would be temporarily transferred to a research institute in Berlin, so that she could interview him for a study on social issues. Authorities granted the request, and Meinhof, with the assistance of three other gun-clad young women, managed to spring Baader back into the radical underground. Shots were fired, and an institute employee was gravely injured, but the operation was otherwise successful. Baader and Meinhof jumped out of one of the institute’s windows and into the headlines of the national media, where their actions—no longer haphazard delinquency, but now considered to be an organized conspiracy—would dominate the news for years to come. Branded as enemies of the state, the militants escaped to safe houses in Berlin and then moved on to Jordan, where they trained with Fatah forces, drilling maneuvers that they would put into practice when they returned home to Germany.

Before the RAF was formed, future members of the group were being initiated into various modes of protest and resistance. In June 1967, during the Shah of Iran’s visit to Berlin, German dissidents demonstrated against unlawful U.S. and British involvement in Iranian affairs. Mohamed Reza Pahlavi’s security detail harassed the crowds with its batons and provoked a violent frenzy—guards pitted against protesters pitted against city cops. The Arab-Israeli War was about to break out, and tensions were high in European cities; record-breaking ranks of police were dispatched to the Berlin demonstration. During the event local...