![]()

Ch’oe Myŏngik’s doubt-ridden hero suffers from a dilemma common to characters in Korean fiction written as the fascist militarism of Japan tightened its hold on its colony: an inability to imagine the future other than as a relentless repetition of the present. Morning and night Pyŏngil trudges along a narrow path through the slums on the outskirts of the city of Pyongyang to reach the office where he works as a clerk in the new and expanding industrial development zone. An interruption of this routine, in the form of an encounter with a photographer running a small portrait studio on Pyŏngil’s route, merely serves to heighten the sense that permeates the story of stymied stasis in the midst of a rapidly transforming urban environment. While Pyŏngil’s route is literally teeming with densely described insects and amphibians, slum residents and passersby, Pyŏngil himself remains isolated and frustrated in the simple goal of gaining the trust of his employer and, hence, a reference. The photographer, meanwhile, has risen from poor studio apprentice to proud studio owner and is eager to dispense advice on his own upward mobility: “The greatest pleasure in the world is to sit in your own home—however small it may be as long as it is yours and not rented—and then you maybe run a business and eat and save anything left over little by little.”1 Such aspirations fill Pyŏngil with disgust, not because he himself shuns work and routine, but because he declares himself to have little faith in turning time “upside down” and saving money for a future that might never arrive. As if to affirm Pyŏngil’s position, by the end of the story the photographer has died suddenly in a typhoid epidemic. The contingent nature of time has undermined the ideology of a guaranteed future, the faith in progress and economic possession as a passage to a better life.

Around the time Ch’oe Myŏngik (1903–?) was writing in 1936, cultural critics too began to question the nature of the future, or, more specifically, its apparent disappearance in narrative forms. Perhaps none felt this as intensely as the erstwhile revolutionary poet Im Hwa (1908–53), who as a member of the Communist Party had led the Korea Artista Proleta Federacio (Korean Artists’ Proletarian Federation, known by its acronym KAPF) in its heyday of the late 1920s and then found himself walking into a police station to declare its formal dissolution, under intense persecution, in 1935. In the aftermath of that immense frustration, Im had turned his attention to his other occupation as literary critic, leaving behind hundreds of pages of ruminations about his present, or, to be more precise, how poets and novelists were narrating that present. As Im cast his critical eye over fiction in Korean in the wake of the collapse of KAPF, he was dismayed by what he saw: not only did it seem to lack the unitary direction that the political impetus of KAPF had aimed to impart, but its very nature as narrative seemed to be breaking up, leaving mere mosaic-like pieces that could hardly be entrusted to portray a sustained critical force. The problem was not just that different stories were being told or that some writers seemed more interested in the past than the present, but that the capacity to portray the temporal logic of development, of cause and effect, and with it the forward-moving thrust of revolution, seemed to be disappearing amid a proliferation in narrative detail that he considered to be entirely unruly. If the revolution could not even be imagined or narrated in fiction, it was hard to see how it might happen on the streets.

What is striking is how the metaphor Im used to describe this fiction of disconnected detail and futureless orientation resonates with Ch’oe’s own preoccupation with the photographer’s studio. In an essay on the set’ae sosŏl, or novel of manners, that he considered representative of this particular trend, Im described such fiction as “the representation of daily life habits where dense and fine detailed description unfolds like the film of a moving picture.”2 Ironically for Im, the former movie actor, just as fiction had become cinematic, this subverts his revolutionary agenda, or so he believes. The rhetoric of Ch’oe’s story, too, owes much to the cinema: Ch’oe stages the opening scene with a filmic slow zoom in to Pyŏngil as he winds his way through the alleys to work, and later in the story a strange doubling of Pyŏngil emerges from him lying in bed and watching on his ceiling “those scenes of daily life he had witnessed and heard on that road.”3 But here, as in Im’s complaint, it is cinema as a series of static images—of photographs—rather than as the motor of a decisively unfolding narrative, that draws Ch’oe’s attention, and it is the world of the studio photographer that gathers both thematic and formal import.

That world sets the stage for a debate over the ideals of a class rising to new prominence in the wake of the collapse of the leftist movement and acceleration of the war economy. In Ch’oe’s work the photograph figures the doubled existence of the petite bourgeoisie stranded between ruler and ruled and living out their lives on the edges of expanding cities. Both Im Hwa and Ch’oe Myŏngik associate the technology of the camera and the world it represents with this class, and with the new visibility of something called daily life and its disaggregation into disconnected detail. Yet would this mean that the photograph could only figure the sense of a disappearing future, or could it also offer strategies for disrupting the routines of colonial bourgeois life?

THE LANGUAGES OF COLONIAL PHOTOGRAPHY

“I’m in the habit of always thinking of fiction in relation to pictures,” wrote Ch’oe Myŏngik in a later essay collection, Thoughts on Writing.4 In a small but significant corpus of short stories produced throughout the late 1930s and early 1940s, Ch’oe built up a reputation as a writer of refined technique, a self-styled craftsman whose craft was the fashioning of detailed description of a density previously unknown in modern Korean literature. In his own descriptions of his style, he dwells on the importance of sketching to his writing practice and its nurturing of two capacities in particular: precision and the power of observation. Precision produces, he writes, the beauty of the right word being in the right place, a notion of order understood along a visual model of his “desire to describe and narrate precisely what I wanted to say, the characters and scenes I wanted to show readers.”5 In other words, Ch’oe’s conception of narrative entailed the appearance of protocols of description and use of detail which in his contemporary semiotic order were deemed commensurate to the production of the perception of a visual image. Yet this modeling of writing on the mode of perception associated with sketching and photography was just as much about nurturing a “power of observation” as sketching objects more accurately.6 It was about nurturing a particular observational viewpoint. Thus the visual training that arose with photography and practices of sketching is equally implicated in the production of a certain kind of subjectivity. That subjectivity becomes more concrete in the photographic images of Ch’oe’s time and in the material history of photography in the colony and its meanings, significations, and representations.

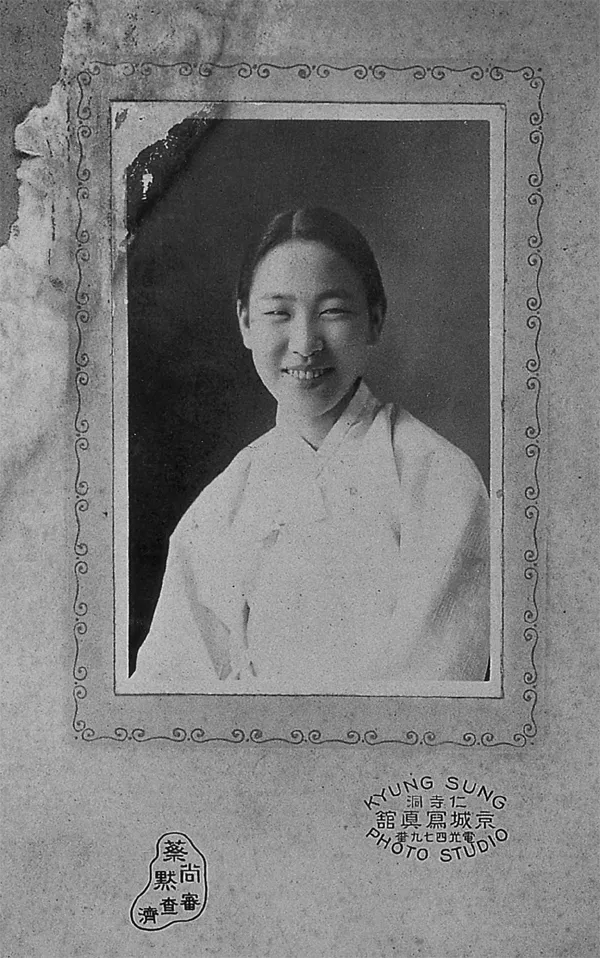

The scene chosen by Ch’oe for his photographic tale in “Walking in the Rain” (“Pi onŭn kil,” 1936) is the interior of the portrait studio. The protagonist Pyŏngil shelters under its eaves one rainy day on his walk home from work. Thus begins his encounter with the portrait photographer. Ch’oe describes a small, shabby affair located on a peripheral street of Pyongyang. In the display window, made from a simple pane of glass inserted into a hole in the wall, faded and bent photographs of girls from the local rubber factories hang on a background of blue wallpaper decorated with a gold foil pattern and spotlighted by a bare 16-watt bulb. Inside, a sliding door opens to reveal a sloping glass ceiling casting dim light down on a hung background painted with a tree and before it a sofa and a small table, on which stand a European-language book and pot of narcissi. When the electric light brightening the tiny room is switched off, the narcissi seem to revert to a China ink painting in the eyes of Ch’oe’s protagonist, Pyŏngil. It is a reversion that recalls the origins of early photographic genres in those of painting, specifically portraiture. Even the term that eventually stabilized as the sign of the photograph, sajin, holds within it the early term ŏjin, just one of the terms that referred to a painted portrait (of a monarch). Early portraits of the 1900s followed the generic rules of painted portraits, tending to capture either the entire body or a three-quarter view of the subject either standing or sitting and facing forward, as omitting a body part was supposed to deny the wholeness of the body inherited from one’s ancestors. The sitter dressed in accordance with his or her status and most often sat or stood beside a table, covered with a table cloth and holding a vase or potted plant, typically an orchid or small bonsai tree. Such stylized portraits were typically taken in a photograph studio, which provided the appropriate accoutrements, as well as light and warmth in winter for the relatively long sittings, which were required initially due to long exposure times.

For many Koreans the first experience of having their photograph taken came through the medium of the portrait photograph and thus with the symbolic space of the portrait studio. In his magisterial history of photography in Korea, Ch’oe Injin wrote at length of these studios, which in the first instance embodied technological modernity but also a shift from a social order in which only high officials or royalty had their portraits painted to a society in which anyone who paid could be photographed.7 This association of the photograph with a commodity-driven society in which the mastery of technology could provide upward mobility continues into Ch’oe Myŏngik’s story, where the photographer has completed an apprenticeship in another studio, borrowed the money on installments for his own camera, and now dreams of moving to a studio with an advertising sign in a downtown street.

At first Koreans had to travel to studios in Shanghai and Beijing to have their portraits taken, but from 1882–83 the first portrait studios began to appear in Seoul.8 These early studios had demanded a significant investment of money, not only for the camera equipment but for the building itself. Before the widespread availability of electric light and film and processing techniques that could produce good photographs in artificial light, the studio ideally had both a south-facing window and a north-facing glass roof to allow enough natural light to enter the room where subjects sat. In general the one-story design of the Korean house (hanok) was too dark to satisfy these requirements, and portrait studios tended to be built in a Western or Japanese two-story style, with a reception room downstairs to admit and entertain customers and a studio upstairs with a glass roof to take the utmost advantage of natural light. By the 1930s, however, wider availability of electric light and new development technology meant that the building itself bore a less onerous burden to allow the taking of photographs. In turn, camera equipment was becoming cheaper and more widely available, and, according to Ch’oe Injin, with the rise of the amateur photographer the glory days of the portrait studios and their virtual monopoly on camera technology had passed.9 By 1936 a portrait studio could offer a determined apprentice the opportunity to support his own family and dream of a better financial future; it had, in other words, become one paradigmatic route for a petit bourgeois dream.

In his story Ch’oe Myŏngik points to the time of the studio interior as one of development—of photographs but also of that petit bourgeois dream. He also calls attention to the photographic frame as Pyŏngil pauses before the photographs of the factory girls and imagines their rough, laboring hands, which are omitted from the portraits of their made up faces. The photograph is held responsible for representing a certain view, and one that here disguises and prettifies another, related form of development: the industrial development shaping the city of Pyongyang, Ch’oe Myŏngik’s hometown. The interior constituted by the photograph and the studio tries to disguise the harshness of the physical process while remaining inextricably entangled with it.

Urban photographs of the time tended to depict cities as either clean and bright centers of commerce or monumental displays of colonial power. Photographs of Pyongyang depict a booming, orderly city with a steady horizon of two- and three-story buildings lining the flats of the Taedong River. Pyongyang was fast becoming known as an industrial center on the peninsula, a center not for government but for a proliferating petite bourgeoisie. As early as the turn of the twentieth century, with its extraordinary concentration of Christian missionary activity and a medley of educational institutions, Pyongyang had already produced a distinctive form of proto-bourgeois culture. By the 1930s Pyongyang had become not only a center of education and churches but also a large commercial and industrial city, which was the final major stop on the railroad running from Japan and reaching into Manchuria. In a roundtable discussion organized by the best-selling magazine Chogwang as part of a series focusing on regional cities, distinguished Pyongyang natives boasted of the city’s long history and role in the dissemination of both Buddhism and Christianity across the country, though at very different points in history; its strategic position at the “center of East Asia” with the opening of shipping lanes between Pyongyang and Shanghai and cities further to the north; and the modernity and culture of its inhabitants who, they argued, regularly used Western medicine and crowded into the city’s libraries every day.10 Industriousness was said to characterize the people of Pyongyang, as the visiting Chogwang journalist wonders at the sounds of knocking and chipping emanating from inside all the houses, clearly audible from the street, and speculates that home industries are widespread and form a foundation for Pyongyang’s larger factories.11 In his description the interior is literally a site for industry.

FIGURE 1.1. 1920s studio portrait by Yi Honggyŏng. Hangilsa.

FIGURE 1.2. View of Pyongyang. Somundang.

Photographs of Pyongyang obey their own set of generic conventions in what might be called the picture postcard urban mode. Here a major road rises and cuts diagonally across the center of the postcard before disappearing on the horizon. Streetcars, pedestrians, cyclists, and horse-drawn carts pass each other on the street in an orderly fashion. Chimney stacks dot the horizon as if to testify to Pyongyang’s status as up-and-coming industrial center; telegraph poles line the streets to point to the presence of electricity; and, above it all, two biplanes hover over the buildings. The photograph is taken from an elevated position, a commanding viewpoint looking down and across the city and into the horizon. This is the city, the photograph appears to say, and it is a center of modernity and, above all, circulation—of people, of traffic, of commodities. Such visions of the city can be found again and again in compendia of photographs of colonial Korea, such as in the two volumes of the Survey of Japanese Geography and Customs published in 1930 that cover ...