![]()

1

THE STRANGER PERSONA

IN THE days after Hurricane Katrina, the uproar over the lack of disaster preparation and mismanagement of emergency funds dominated political discourse while a less noticed controversy was unfolding over the use of the term “refugee” for the hurricane victims. The Washington Post interviewed some of the victims seeking shelter at the New Orleans convention center and reported that they all felt insulted by the term. Elijah Cummings, democratic representative from Maryland and member of the Congressional Black Caucus, echoed the response: “They are not refugees. I hate that word.” The term even prompted a presidential intervention. Upon visiting the destroyed region and meeting the survivors, President George W. Bush urged the use of alternative phrases to describe the status of those recently made homeless. He even offered a few suggestions: “evacuees,” “victims,” or simply, “displaced citizens.” This last phrase seemed ready-made to address the frustration of Annette Ellis, one of the displaced Baton Rouge residents interviewed by the Washington Post, who insisted in simple and clear words: “We ain’t refugees. I’m a citizen.”1

“Why is the term such a dirty word to some?”—asked the Washington Post.2 After all, it was only a metaphor. However much the victims had lost in the hurricane, they still had their citizenship. To call them “refugees” was to throw into question some of their most important rights. The disaster left its victims homeless, unemployed, and in precarious health. They were dependent on state and federal assistance and the rest of the American citizenry now saw the displaced as a political problem and an economic burden. Their status was not radically different from that of a refugee arriving from Somalia or Rwanda.

More than terms like immigrant or exile, “refugee” emphatically references the foreigner as a noncitizen and an overall rather sorry figure. Public imagination captures this representation well through (often racialized) images of extreme poverty, illiteracy, and disease—features of a diminished subjectivity. The objections of Katrina victims at being identified as refugees show the anxiety created by the subjectivity assigned to them, the subjectivity of the noncitizen deprived of rights, at the mercy of others. The figure of the refugee emerges from historical, political, and policy documents as a “pure victim in general: universal man, universal woman, universal child, and taken together [all refugees] universal family.” “This universalism,” Liisa Malkki claims, “can strip from them (the victims) the authority to give credible narrative evidence or testimony about their own condition in politically and institutionally consequential forums.”3 Even more so it strips from them the authority to draw on their own experiences to offer insight into the politics of their adoptive nation.

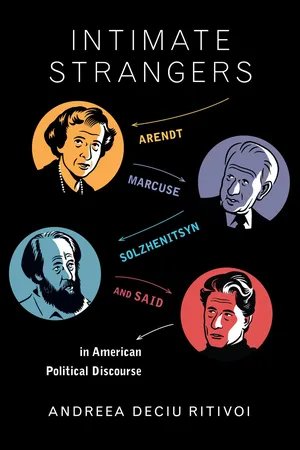

Readers looking at Arendt’s picture on the covers of her books did not see a poor refugee in the woman seated comfortably in an armchair and smoking a cigarette. Nor did they see one in television interviews with Herbert Marcuse, a white-haired man in black suits and bow ties. Said’s physical appearance, that of a scholar with a pensive look, hardly inspired Palestinian refugees. Even Solzhenitsyn, a hirsute in Russian peasant garb, looked defiant and self-assured, not destitute and needy. Such intellectuals cannot be refugees, it would seem. If they were poor, their poverty was bohemian; if they were ill, their disease was romantic. They were certainly not illiterate; if anything, it was American students who must have fidgeted under the professorial gaze of these foreigners. Yet all four of them were, or self-identified at some point, as refugees: Arendt and Marcuse in the most straightforward sense of the term, as political refugees from Nazi Germany; Solzhenitsyn as a member of a larger category of refugees from the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries (even though he, in particular, was expelled); and Said as a spokesperson for Palestinian refugees forced to live outside their homeland.

We find it difficult to think of them alongside refugees from the Third World and “the babies in Africa that have all the flies and are starving to death”—to use an image that was especially disturbing to one of Katrina’s victims.4 Intellectuals who have fled their countries, or were forced to leave, are more commonly called exiles rather than refugees or émigrés rather than immigrants. Word choice matters. It could be that the term “refugee” is deemed too unsavory to be assigned to an elite group but even more likely that it is made unavailable. In 1940, as the first waves of middle-class, intellectual Europeans fled to America, Life magazine scorned them as “refugees de luxe,” depicting them as well-to-do foreigners in fur coats at upscale restaurants, living in luxury hotels or vacationing at expensive resorts, while presenting themselves as refugees.5 Fortune magazine was equally dismissive of these refugees’ plight: “The pilgrims of the seventeenth century came here to make their fortune; the émigrés of 1940 have come here to protect theirs.”6 To not identify these intellectuals as refugees is to keep them symbolically at a distance from their new political environment, as their commitment is expected to be to the homeland, and their sojourn, temporary. Intellectual refugees (writers, artists, and academics) once seen as uprooted from their homeland can be in an even more precarious situation than other refugees.

Underlying all other representations of the foreigner in a nation-state—exile, immigrant, refugee, and asylum seeker—is a subjectivity defined by inferiority to the citizen as native born. The litmus test of this inferiority is that foreigners must face racially and morally inflected residence and naturalization requirements (such as passing IQ tests or the expectation to not have been involved in prostitution), which decide if they deserve to be allowed into the national community. At the other end of these requirements for admission is a deportation system designed to eliminate those deemed undesirable to the nation-state. The modern deportation regime emerged from a conception of citizenship as full membership in the constitutional community of the nation, which assumes that the citizens are “the people,” “whereas noncitizens are something less.”7 Deportation decisions can resort to denaturalization if someone who is legally a U.S. citizen is deemed undesirable. The foreign origin, then, makes one vulnerable in a way that can never go fully away. Even when legally drawn into the nation, the foreigner inhabits a precarious position, not just politically, but also ontologically, because citizenship is not simply a political category but also commonly imagined as a natural condition and articulated in a series of metaphorical representations of place and nationhood as roots that ground the citizen. The uprooted, by such logic, falls outside not just a national but also a natural order. “The powerful metaphoric practices that so commonly link people to place,” Malkki argues, “are also deployed to understand and act upon the categorically aberrant condition of people whose claims on, and ties to, national soils are regarded as tenuous, spurious, or non-existent.”8

While they can fulfill some residence and naturalization requirements more easily than others, intellectuals are potentially the most threatening instance of foreignness from the perspective of the nation-state. In 1919, Emma Goldman, a Russian national who had lived in New York since 1885 where she was an active writer and public speaker on women’s rights, social issues, and anarchist politics, was denaturalized without notice and deported to Russia as an “alien radical.” Goldman is not the only case of a foreign intellectual deported on the basis of dangerous political ideas. In 1955, Jamaican writer C. L. R. James was deported after fifteen years of living in New York and being involved in socialist politics. At the height of the Eichmann controversy, Arendt said to friends, more or less jokingly, that she hoped she would not be deported. Marcuse and Said received hate mail that demanded they leave the country. Solzhenitsyn was invited to go back to communist Russia if he did not like American democracy. These intellectuals, like Goldman and James before them, were highly critical of the U.S. government, yet hardly alone in their opposition. They had American-born allies and partners who did not suffer a similar fate because the state could not force them to leave. One can only wonder: “a citizen might be immune from deportation, but how was a refugee to be sure?”9

The noncitizen’s inferiority cuts across other categories, such as race, class, or national origin, even though each of these has been at times deemed inferior for separate reasons.10 What all noncitizens share is their uprootedness perceived as a fall from the national order, which renders them fundamentally deficient and suspect. Being white, Western European, and highly educated has only been a partial remedy to such deficiency. Granted, American immigration law has consistently privileged white European immigrants, especially if they had a Christian, preferably Protestant, religious orientation. These were often seen as the stock America was originally made of, and hence more likely to fit in the fabric of the nation.11 Yet the push and pull of immigration also meant that these white European Christian immigrants belonged to a particular class: they were usually farmers or unskilled laborers who arrived empty-handed and achieved socioeconomic success. Ironically, low class status could facilitate Americanization; as throughout much of the nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth, the process of Americanizing immigrants was forged through education.12 By contrast, intellectual migrants came with a completed education and were unlikely enrollers in Sunday school or after work language and cultural programs. Indeed, some encountered other Americans by acting as their teachers rather than students. Challenging Hannah Arendt’s negative remarks on American foreign policy, Nathan Glazer once referred to her sarcastically as “our teacher.”13 While seemingly acknowledging her intellectual authority, Glazer questioned her political wisdom by emphatically putting her on a different level from “regular” Americans and rendering her inassimilable to the community that she was addressing. How could a perspective like hers be other than irrelevant, theoretically sophisticated perhaps, but surely impractical?

Laura Fermi estimates the financial contribution wartime European intellectuals made to American society by being ready to contribute immediately to the workforce at $32 million, without any investment from the U.S. government required for their training.14 Yet, as the label “refugees de luxe” suggests, their reception was far from enthusiastic. As I show in the introduction, American officials suspected many of them of subversive political activity, even as the State Department employed several intellectual refugees in the war intelligence effort.15 Surveys published in popular magazines and newspapers of the time along with articles and letters to the editors indicated a general anti-immigration sentiment in America. Almost 80 percent of the population expressed negative feelings about intellectual refugees from Europe.16 As the Life magazine article shows, intellectual refugees got caught in a double-bind of rejection, on the one hand simply as foreigners, and on the other hand, as impostors. Ironically, then, they were doubly inferior.

Yet no matter how critically they were received at times, Hannah Arendt, Herbert Marcuse, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and Edward Said succeeded in becoming political commentators in the United States and frequently voicing their opinions, even the most critical ones. How did they formulate their ideas and position given the constraints exerted by a political discourse structurally and historically set up to keep foreigners at bay? To begin my investigation, in this chapter I look more closely at the politics of foreignness and its rhetorical valence in postwar America to articulate the general framework in which I examine the particularities of the stranger persona in each of my four case studies. My goal is to conceptualize foreignness at the intersection of political practices of stratecraft and rhetorical practices of de-familiarization (or estrangement), drawing on Victor Shklovsky’s work. These practices converge in the figure of the stranger, which I take from, but also expand upon, the sociology of Georg Simmel and Alfred Schutz.

This chapter, then, lays the foundation for the overall argument of the book: the four foreign intellectuals I study here developed a stranger persona that was not the mere consequence of maladjustment, or a rejection of American mores, but rather a strategy of invention and delivery created in response to the political subjectivity of the foreigner. In their criticism, these intellectuals offered a portrait of the American nation. In their audiences’ responses, we discern a different image of America. Looking at these images side by side, I am less concerned with whose depiction was more accurate and more interested in the tension between the underlying representations. It is this tension that gives us a unique measure of civic engagement in America, of its ambivalence toward plurality and its cautiousness toward ideas that could inspire political renewal.

THE CITIZEN’S ETHOS

Political life relies on rhetorical acts: decisions that are made and enforced by the members of the community based on the arguments they find most compelling. Aristotle saw such political-cum-rhetorical activity as the rational byproduct of the natural inclination of human beings to live together and achieve certain goals that are valid and desirable for all, rather than only particular individuals. Politics—and political discourse—brings individuals together in a “sort of partnership.”17 But did foreigners also belong in this partnership? A foreigner himself, Aristotle did not participate in Athenian politics, but he was a key player as advisor to Alexander the Great, whose thinking and policy he influenced directly. What kept foreigners out of political deliberation was not only their inferior social status, but also, and connectedly, their lack of a citizen’s ethos.

In the classical rhetorical tradition, the genre of political deliberation required that in order to convince an audience the speaker display ethos, or moral character, usually associated with a well-defined set of characteristics: practical wisdom, virtue, and goodwill. The complete list of virtues included courage, temperance, magnanimity, liberality, gentleness, prudence, and justice. Greek culture did not define these virtues in the abstract terms of a moral theory but as ethical conventions shared by a community. Practical wisdom, for instance, referred to the capacity to identify what is beneficial for the community in certain circumstances, which, in turn, depended on what the members already took for granted as being “beneficial.”18 Virtues were context- and culture-specific, set up by “an ethics of citizenship to parcel up humanity into different natural types.”19

The classical conception of ethos carries an unacknowledged legacy of ethnocentrism, not only because ancient rhetoric saw the circumstances of a person’s birth as an “intrinsic and essential part of an individual’s identity,” but also by disadvantaging rhetorically those whose status was deemed socially and politically inferior. Moreover, in the Nichomachean Ethics Aristotle implicitly linked ethos to the self-image of a community by claiming that ethos develops through custom and education, in other words throug...