![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Nation, the State, and the Cinema

Nations are made, not born. Or rather, to exist they must be made and remade, figured and refigured, constantly defining and perpetuating themselves. Classic distinctions in political and social theory differentiate nation and state. Nations are cultural, discursive fields. They are imaginary, ideal collective unities that, especially since the nineteenth-century era of nationalism, aspire to define the state. The state is an institutional site constructed as overt repository and manager of legitimated power. Nation is on the side of culture, ideological formations, civil society; state is on the side of political institutions, repressive apparatuses, political society.

PHILIP ROSEN (2001)1

On the morning of 7 November 1987, Tunisia’s recently appointed prime minister, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, broadcast a startling message on national radio: “The enormous sacrifices made by the leader Habib Bourguiba, first President of the Republic, with his valiant companions, for the liberation of Tunisia and its development, cannot be numbered. However, faced with his senility and worsening state of health, based on a medical report, national duty obliges us to declare his absolute incapacity to carry out any longer the office of president of the republic. We, therefore, take over with God’s help the presidency and the command of the army … we are entering a new era.”2

This news was met with a collective sigh of relief by Bourguiba’s countrymen. He had remained in power too long. The Supreme Combatant, as he had come to be known (and officially “President for Life” since 1975), had started to have a paralyzing effect on the country’s economy at least a decade earlier.3 But Bourguiba’s forceful, charismatic personality and his ruthless consolidation of political and personal power, beginning even before the abolition of Tunisia’s monarchy in 1957, had over the course of thirty years come to have a paralyzing effect on the Tunisian people as well, producing a kind of psychological malaise from which, many felt, only his death would liberate them.4 In his biography, Habib Bourguiba of Tunisia: The Tragedy of Longevity, Derek Hopwood summarizes Bourguiba’s rationale for hanging onto power into extreme old age and infirmity by imagining a rhetorical conversation the eighty-six year-old president has with himself. Visibly frail and demonstrably senile, the delusional octogenarian muses: “Tunisia still needs me. I cannot have stayed too long as I was elected president for life. No-one is fit to take over. I have had to dismiss Mohammed Mzali, my prime minister and friend, I have divorced the love of my life, Wasila, for intriguing, I have had to send away my son. Who is there left to trust? Is Tunisia ungrateful to the man who forged its history? I have fought and suffered all my life for my people. When I die what will they do without me?” (1).

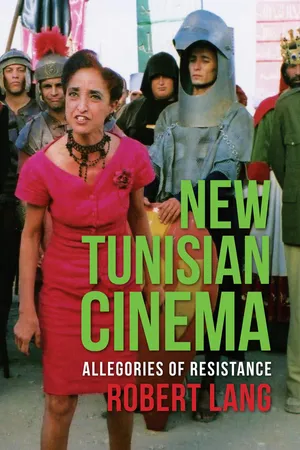

FIGURE 1.1 The Picnic (Férid Boughedir, 1972), released in 1975 as part of the omnibus film, Fî Bilâd al-Tararanni, an early attempt to make “the first specifically Tunisian film.” (The picnickers’ vehicle, a symbol of the East–West hybridity of Tunisia under the French protectorate, breaks down.)

If “few Tunisians mourned the end of Bourguiba’s sixty years of public life,” Ben Ali’s bloodless coup was the best possible way to bring an end to a situation that had become intolerable.5

For readers unfamiliar with or rusty on the rudimentary facts about Tunisia and how it became a French protectorate—which is where, for better or worse, I must locate a beginning and sketch a “backstory” for this study of contemporary Tunisian cinema—Hopwood’s summary will serve our purpose:

Tunisia is a small country, only 500 kilometers long and some 175 wide. To the north are fertile areas, to the south stretches the desert. The capital, Tunis, center of government, the upper classes and cultural life, is near the northern Mediterranean coast; Monastir [Bourguiba’s birthplace] lies in the Sahel (coastal) region, a fertile area of olives, palms and wine growing stretching some 150 kilometers along the eastern side of the country. … In 1881 the French had persuaded the then Bey, a prince of little character or “instruction,” to sign a treaty allowing them to install a protectorate over his regency, in practice signing away all independence. There is a French resident-general who becomes foreign minister and has the right to promulgate legislation after signature by the Bey. Tunisia becomes a French-run colony. The French take up residence, obtain land, and French becomes the language of the government, higher education, and culture. Churches and cathedrals proclaim the religion of the occupiers without regard for local feeling. Tunisians feel second-class citizens in their own country.6

By way of transition to some of the themes I pursue in this book, the last comment in the preceding quotation—“Tunisians feel second-class citizens in their own country”—allows me to flash forward to a remark made in 2002 by Tunisia’s preeminent filmmaker, Nouri Bouzid, during an interview he gave in France about his new film, Poupées d’argile (Clay Dolls): “We don’t own the streets where I live.”7 Bouzid had spent over five years in Bourguiba’s jails (1973–1979) for his membership in a socialist youth group. But here, in 2002, he is acknowledging that in the area of civil and human rights, things had not improved in Tunisia since the colonial era or the darkest days of Bourguiba’s presidency. Most would agree they had grown worse. As Florence Beaugé observed in Le Monde in June 2003, in a short article entitled: “In Tunisia, a ‘Cycle of Injustice’ Is Perpetuated,” the objective of “the palace in Carthage” in creating civil and human rights organizations in Tunisia was not to protect civil and human rights in the country, but to improve Tunisia’s image abroad.8 The new Amnesty International Report, she wrote, confirmed that “on grounds of maintaining security and countering the ‘terrorist threat,’ political and civil liberties in Tunisia remain subject to significant restrictions. As for defenders of human rights, such as the members of the LTDH [Tunisian League for Human Rights] and the ATFD [Tunisian Association of Democratic Women], they are targets of ‘systematic campaigns of intimidation’: illegal searches, anonymous phone threats, suspensions of telephone service, arbitrary detention, passport confiscations, violent physical attacks, defamation in the media, etc.” (29–30). Beaugé wrote that the report goes on to denounce “the systematic interference of executive power in the functioning of the justice system” in Tunisia, where equal rights as defined by international law and guaranteed by Tunisian legislation are “violated at every stage of the legal process.” The resort to torture of individuals caught in the justice system is common (30).

If Bourguiba’s (undeniable) accomplishment, with his valiant companions, was the liberation of Tunisia from French colonialism and his (also undeniable and altogether remarkable) social development of the newly independent country, then Ben Ali’s accomplishment was the liberation of the country from Bourguiba, and (in due course) the country’s apparently spectacular economic development, the so-called Tunisian “economic miracle.”9 But both leaders became dictators whose suppression of all oppositional voices would become so suffocating that the nature and value of the “development” for which each is known and praised would be called into question.

If, as Bouzid put it, “we don’t own the streets” (in Ben Ali’s Tunisia), then this was certainly also true in Bourguiba’s day—although the style of the country’s first two presidents could not have been more different. Like Bouzid, the Tunisian novelist Gilbert Naccache came of age in Bourguiba’s Tunisia, and on the occasion of the Supreme Combatant’s death on 6 April 2000, at the age of ninety-six, he observed that “today’s despair has its roots in yesterday’s misery.”10 As will be revealed in the films analyzed in the chapters that follow—films that nearly all date from the Ben Ali era—the causes of this “despair” to which Naccache alludes would change little, if at all; only the infrastructure of the dictatorship would evolve. “The difficulty of speaking, of writing, even of breathing—that is not new,” Naccache wrote (224). Bourguiba, who was a brilliant orator and compulsive autobiographer—a raging narcissist of phenomenal proportions, who sought to make Tunisia in his own deeply secular and Westernized image and whose presentation of himself as the “father” of the country would have disastrously infantilizing effects upon the population, particularly its male members—was a very different creature from Ben Ali, who was secretive, uncharismatic, “heavy.” But in their suppression of free speech and their addiction to political power, the two men came to resemble one another.

The key element that secured the continuity between Bourguiba and Ben Ali and kept Ben Ali in power almost as long as his predecessor was Ben Ali’s commitment to secularism and his deft manipulation of Tunisians’ fears in that regard, which would be periodically exacerbated by events beyond Tunisia’s borders, such as the chaotic aftermath of the victories in local elections of the FIS (Front Islamique du Salut/Islamic Salvation Front) in neighboring Algeria in 1990 and the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States in 2001. “In exchange for protection from the ‘green threat’ of Islamic radicalism,” Kenneth Perkins observes, “the majority of secular Tunisians turned a blind eye to excesses committed by the authorities” (194).11

Writing in 1995, Eva Bellin notes about the development of civil society in Tunisia (where her references to the “state” can, in my more allegorical reading of the political economy, be taken to refer to Ben Ali):

While the country has made notable progress in combating some common sources of despotism (nurturing a culture of civisme and civility, dispersing the loci of economic power in society, expanding the reach of some democratic institutions), it has still failed to achieve one important goal—the institutionalization of contestation sufficient to impose accountability upon a despotically-tempted state. The responsibility for this failure lies squarely with the state, driven as it is by contradictory impulses to foster the development of civil society on the one hand, but also to contain the latter’s development so as not to cede political control.12

It is sometimes boasted that Tunisia’s short-lived Constitution of 1861 was the first for an Arab country, but as Perkins points out, it was imposed by the French and British consuls and had little indigenous support. And as far as the Ben Ali era is concerned, the “contradictory impulses” Bellin refers to were there at the dawn of independent Tunisia’s making. Even at the beginning, Bourguiba’s embrace of liberal values did not extend to the tolerance of contrary views.13 Naccache writes that under Bourguiba:

Every word, every line you wrote, every step you took in those days was the product of a constant struggle against fear, and against the negative opinion he wanted us to have of ourselves. He pitted his brainless secret agents, the bright lights of his regime, against what he saw as “pseudo-revolutionaries fresh from the Latin Quarter.” And like all his confreres, whether nationalist despots or phony socialists of totalitarian states, he mocked everybody’s intelligence except his own. He heaped his scorn on us, and called on the people—of whom he was equally contemptuous—to despise us for using our intelligence. (224)

And, the novelist ruefully acknowledges, Bourguiba to some large degree succeeded in making the people devalue the society’s intellectuals. Naccache describes how, when he was arrested by the regime and thereby lost his livelihood, he had to move his family out of their house and into a smaller, more affordable one. On seeing the task before them, one of the two movers helping the writer remarked gravely to the other: “It’s not surprising that he was arrested, with all these books” (224–225).

“Yes,” Naccache tells us, “under Bourguiba, culture was suspect, dangerous. And is this still the case? Indeed it is. But it goes back a long time. You wrote with a copy of the Penal Code under your arm. You had to be careful—a single word or turn of phrase could get you a year in jail, five years, ten. You’d change a phrase because they could interpret it in such a way as to invoke Article 62 or 68” (225). There is no question that Tunisia under Bourguiba had become a police state—the difference is that under Ben Ali one talked not so much about a man as about a system, of which Ben Ali had been the chief architect since 1987.14 When Naccache writes in the year 2000 about the Bourguiba of yesteryear, he is explaining how Bourguiba’s Tunisia became Ben Ali’s Tunisia.15 The foundations were laid by Bourguiba—both the regime and the man, in that way in which a very strong personality can leave a deep imprint on institutions and the collective psyche for generations to come—but now the house (or prison) was built, and General Ben Ali had the keys.16

National Disenchantment

In 1982, when she was thirty-four, the Tunisian writer Hélé Béji published an essay about decolonization and its discontents in her country: Désenchantement national: Essai sur la décolonisation.17 It attempts to explain the trajectory, which began on 20 March 1956, when everything seemed possible—when, in her striking phrase, “Liberty began to cross the street and History to descend the stairway of our small, familiar world”—and which led to the malaise that set in too soon afterwards.18 Béji imagines her countrymen on that historic day in 1956, released from the yoke of colonialism, caught up in the “unpredictable quickening of national vitality, progress, liberation, and development” (9); and then she contemplates the present disillusionment:

Why does something still weigh on us in this indistinct and ferocious manner? What is neocolonialism? What is this other, ungraspable thing that has appeared since independence? Why this tremendous feeling of impotence in our thinking and in our social conscience in the face of the absence of liberty and democracy? Why was democracy not born with independence? Why have nationalism and anti-colonialism not been a force for liberty? Why has our national political universe become so closed, so crushing? (13–14)

Béji observes that Frantz Fanon’s axiom that “the death of colonialism is at once the death of the colonized and the death of the colonizer” is simply not true. Rather, when the colonizer departs, the energies that were expended in resistance to colonialism or that went into anti-colonial dreams of independence do not dissipate but inscribe themselves deepl...