![]()

1

ON DRAWING; OR, THE SPEED OF THOUGHT

No distance between the thought and the hand: their instantaneous unity grasps and redraws the most concentrated interiority into visible bodies. No trial and error: the artist’s mind, identified with the gesture, trims away the expanse, carves out shadow and light, and, on the flat exteriority of a medium like paper, makes an intention, a judgment, a taste appear, voluminous. Simply through the precision of the lines, their placement, their movement, where they thicken into darkness, where they thin out into light. Drawing has always seemed to me the proof of a maximal concentration through which the most subjective intelligence, the most intense abstraction, makes something exterior visible and suddenly perceptible to the artist and nevertheless so intimately connected to the viewer that it registers, equally absolute and singular, as proof. Operating with only the given means—lines and spaces—the drawing not only links contemplation to action but also, and most importantly, the drawer to the viewer, in the striking certainty that together they create the visible. The drawing: crucial evidence of humanity’s subtle mastery of the exterior and the other, which we call talent.

Perhaps I arrived at this perception of drawing because my mother was the first person I knew who could draw. A face, a landscape, an animal, a flower, an object: her pencil suddenly brought them to life, with a precision as surprising as it was natural to her. Without trying, without thinking about it, as though it were nothing, my mother drew the way others breathe or embroider. To her this gift didn’t seem like anything unusual: it went without saying; she did not pride herself on it, and it never would have occurred to her to consider herself an artist. As I got older I realized how much this natural talent distinguished her, made her superior to others. And, first of all, to me, more or less successful at painting pictures, thanks to colors and brushstrokes, but never able to inscribe the moment of being, in the spontaneous ellipsis when conception and execution merge, that confers upon graphic arts their concise grace.

One drawing remains etched in my memory, given to me without ceremony but as a sign of favor, in the way that only gifted beings and mothers know how. It was one of those cold, white winters that freeze the Balkans and bring families together around their coal stoves. Hunched over the glowing grate, I warmed my icy cheeks and numb fingers as I listened absentmindedly to a children’s radio show: “What is the quickest means of transportation in the world? Send us your answer, with a drawing to match, on a postcard, to the following address …” “I know, it’s an airplane,” my little sister piped up. “No, it’s a rocket,” I countered, pleased at having the last word. “I’d say instead that it’s thought,” Mama proposed. I could only concede, but not without my usual smart remark: “Maybe, but you can’t draw a thought, it’s invisible.” “You’ll see.” I can still picture the card that she drew with my name on it, which won me first prize in the radio contest. To the left, a big snowman in the process of melting, his head falling off, as though severed by the invisible guillotine of the sun. To the right, the planet earth in its interstellar orbit, offering its imaginary expanses for armchair travels.

In fact, there was nothing special about that drawing. Certainly, the spareness of the sketch, the vacuousness of the melting body, the severed head all merged with an ingenious idea: only the speed of thought exceeds the speed of bodies, whether cosmic, human, or products of human technology. But, to my young eyes, it subtly demonstrated that quickness of thought I so admired in the answer my mother had proposed. The drawing let it be seen, as much in the concision of its concept (a perishable body transcends itself and conveys itself through the power of reason) as in the cheerful quickness of the line (without collapsing into caricature, the nervous, spirited line betrayed the melancholy of our mortal condition as well as the triumphant irony of deep reflection).

This drawing, which my mother hardly remembers anymore, comes to mind occasionally; just recently, I thought I recognized myself in the story of a decapitated woman.1 I recognize my fears of death in its lines: my body is fleeting as that snowman who begins by losing his head before dissolving into a puddle of water. And one of those certitudes that mothers sometimes pass on to us: might not the only credible incarnation be that of thought, which knows how to draw beings because it is able to grasp the vectors of its own speed? To grasp them in the perceptible, beyond the perceptible, by slicing into the perceptible.

It is to that poor drawing I return today as I resolve to bring together a few capital visions and to make apparent the power of drawing, on the border dividing the visible from the invisible.

To introduce this bias, I should say first of all that my mother’s drawing, which only exists now in my own memory, seems, in retrospect, in the direct line of Byzantine icons. In the same way that an icon is not an image that represents a lifelike object but an inscription that invites contemplation, beyond its golden brown imprint a hidden insistence, so the line of the snowman thinking the earth in its celestial voyage evoked the power of thought rather than offering it visually. A graph at the crossroads of the invisible, my mother’s drawing was addressed to the imagination and the heart: captive audience, I adhere to it and I prolong it, as the faith of the believer partakes of the icon that he kisses more than looks at. Another status of the image reveals itself here, which, for better or for worse, we have now lost in the world of “the spectacle.”

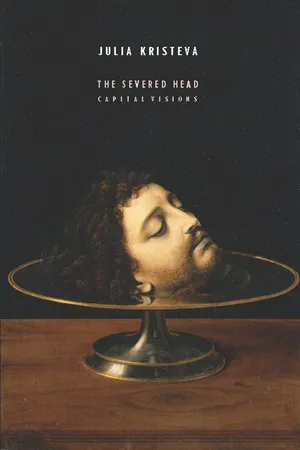

I can’t take my eyes off that severed head. Much as I want to, this is my symptom. Depression, obsession with death, admission of feminine and human distress, castrating drive? I accept all these human, too human, hypotheses. I move on from them to imagine a capital moment in the history of the visible. A moment when human beings were not content to copy the surrounding world, but when, through a new, intimate vision of their own visionary capacity, through an additional return on their ability to represent and to think, they wanted to make visible that subjective intimacy itself: that inner sensibility, that spirituality, that reflective affection, that economy of anguish and pleasure, the soul. That palpation of the invisible surely had confronted them with the fundamental invisible that is death: the disappearance of our carnal form and its most salient parts, which are the head, the limbs, and the sex organs, prototypes of vitality. To represent the invisible (the anguish of death as well as the jouissance of thought’s triumph over it), wasn’t it necessary to begin by representing the loss of the visible (the loss of the bodily frame, the vigilant head, the ensconced genitals)? If the vision of our intimate thought really is the capital vision that humanity has produced of itself, doesn’t it have to be constructed precisely by passing through an obsession with the head as symbol of the thinking living being? Through a cult of the dead head, fixing the terror of sex and the beyond? Through a ritual of the skull, of beheading, of decapitation, which might be the preliminary condition for the representation of what allows us to stand up to the void that is none other than the ability to represent the life of the mind, psychological experience as the capacity for multiple representations?

I am already hearing objections of an airy, impressive, modern, French nature. Might I not be a bit too introverted, grief-ridden, morbid? Psychological life is as much ruled by pleasure as by death, isn’t it? In short, isn’t this bias, well, biased?

I will not respond to my imaginary opposition that I am prepared to qualify my proposals and balance my arguments—a bit of Thanatos, much Eros. I will do nothing of the kind, otherwise there would be no more “bias.” Furthermore, one argument weighs in my favor, which cannot help but prove fundamental, or at least I hope so, because it is not speculative but clinical. Here it is.

Before very young children begin to talk, they become irremediably sad. This transient state, which has been designated a “depressive position,” corresponds to the experience of a precocious, formative bereavement: it transforms the autoerotic baby who enjoys its body parts, its mother’s nipples, a blanket or a doll, into a speaking being. How? Until that time, the future speaker uttered vocalizations that were only the “equivalents” of its needs and its dependence on the maternal body: I call these equivalents semiotics (from the Greek semeion: distinctive mark, trait, indication, precursory sign, proof, engraved or written sign, imprint, figuration). Beginning with a certain neuropsychological maturation and beneficial parental care, the infant becomes capable of bearing the absence of its mother: the separation and absence cause it to suffer; it becomes convinced that it will not have everything, that it is not everything, that it has been abandoned, that it is alone. Some never recover from this first grief: if it seems as though Mama is dead, mustn’t I myself die in turn, die to thought, neither eat nor speak? Nevertheless, most of us replace the absent face, as loved as it is feared, source of joy and terror with … a representation. I have lost Mama? No, I hallucinate her: I see her image, then I name her. From my babbling, which was its semiotic equivalent, I now fabricate word-signs: isn’t the sign precisely that which symbolizes the object in the absence of the object? That which represents, arbitrarily or through convention, its lost referent?2

The future speaker’s sadness is, in the end, a good omen: it means that henceforth one can count on oneself alone, that grief for the other casts one into indelible confusion, but it is not impossible to compensate for that separation … by taking control. By concentrating on one’s own ability to represent, by investing in the representations one can make, one’s own representations of that other, the abandoner, for whom one dies even by making her die. Thus the depressive phase marks a shift from sexual autoeroticism to an autoeroticism of thought: grieving is dependent on sublimation. Have we really fathomed how grief and melancholy line the underside of our languages, our so-called mother tongues? That we speak over and above that depression as others dance on the mouth of a volcano? A body leaves me: her tactile warmth, her music that delights my ear, the view that offers me her head and face, they all are lost. For this capital disappearance I substitute a capital vision: my hallucinations and my words. Imagination, language, beyond the depression: an incarnation? The one that keeps me alive, on the condition that I continue to represent, ceaselessly, never enough, indefinitely, but what? A body that has left me? A lost head?

Hans Baldung Grien and Jean-Baptiste Greuze vision severed heads. What is the pretext for these decapitations—to learn the techniques of the classical masters? To acquire virtuosity? To tame secret fantasies? Even so, these are clusters of sliced off members that accumulate on the paper. Baldung’s nervous line, Greuze’s psychological weight, finally, curbing the violence of these cuts in their concern to expose a capital truth inseparable from the hand that forges ahead. Dürer’s children have swollen heads. Very light brushstrokes, parallel or crossed, exude an already expressionistic shadow over their hydrocephalic bulk. But I would wager that these sad boys are hallucinating other absent skulls, the lost head of their mother, her multiple, fleeting faces. We can compare these Three Children’s Heads to the series of crying children completed in 1521, but also to two of Dürer’s paintings, Feast of the Rose Garlands (1506) and The Virgin with the Canary (1506). Before creating his engraving Melancholy (1514), Dürer here glorifies the Mother of God, drawing his inspiration from the Venetian master Giovanni Bellini. The stamp of the creator of the Sacre Conversazioni is not only evident in the presence of a beautiful angel musician at the Madonna of the Roses’s foot. Dürer had also absorbed the Byzantine sadness of the Virgins, angels, and little Bell-inian Jesus figures that Jacopo’s son to an unknown mother enjoyed perpetuating in his masterpieces. Dürer rendered them more serious under the influence of the German Rosenkranzbild. The rosary, a Dominican invention, alternated a dozen “Hail Marys” with a single “Our Father,” thus combining the “joyous mystery” of the birth and the “sorrowful mystery” of the Passion. No such alternating with Dürer. These children’s heads superimpose the red beads of the Passion over the white beads of Mary: all the black melancholy of the “sorrowful mystery” inscribed immediately in the white roses of the “joyous mystery.”

The journey on which I am inviting you is, as you have probably guessed, largely imaginary. Headsmen no longer haunt our regions, except in the Balkans and in times of grave crises, but that is another story. The only decapitated bodies we come across are those of statues beheaded by time, that another time offers for our admiration in museums. Dione and Aphrodite, Phidias’s lovers, may well have lost their heads, but it was in leaving the pediment of the Parthenon to seek shelter in a cavernous hall of the British Museum. As for the Victory of Samothrace, another decapitatee, she will never take wing from the Louvre; how could she fly without a head? To them I prefer this Head of a Knight: massive, but delicate and gentle; with sealed lips, salient cheekbones, broken nose. This ideal recumbent statue might be of one Jean de Seignelay, lord of Beaumont, who died in 1296 or 1298. It left the hands of the masters in the Burgundy workshop at Mussy-sur-Seine, was interred in the abbey of Prémontrés de Saint-Marien, and was mutilated by the Calvinists in 1567.

That is how the guillotine of history falls, sparing neither men nor works.

![]()

2

THE SKULL

CULT AND ART

But let us return to the head: skull and face.

Does art descend from the metamorphosis of the gods, as Malraux thinks, or does it anticipate the religious rituals of which it is part, by elaborating the same powers and the same virtues? The artifacts produced through “art” since prehistory confirm the second hypothesis rather than the first.1 Before or simultaneous with the invention of gods, many effigies possessed the power to protect prehistoric humans from the spirit world and the night. “Work,” rather than “labor,” our ancestors’ archaic occupation, which produced these objects, had concealing them from human eyes as its extravagant goal. The paradox appears to us alone. Turned toward the dead, intended for the dead, these creations were meant to be restored to them: sent back to the invisible, they were in this sense, literally, “sacrificed.” But, in actualizing that sacrifice, they were permeated with the power to which one sacrificed, the power of life and death. And even when it was displayed, the sacred work was not meant to be sampled by the eyes of the living, as is now accepted in our modern museumized culture.2 When they found their way into the world of the visible, these manmade artifacts continued to intercede with the invisible powers, to transpose their virtues to the living. That was their sacred logic.

In this proto-artistic archaeology, a special place reverts to the worship of the skull: physical medium for the rite of invocation and propitiation of the dead. Nevertheless, in venturing into these archaic regions where science vies with fable, where, everyday, DNA dethrones hypotheses that are, no doubt, dangerous but certainly tenable, we do not seek to compete with either the anthropologists’ erudition or the geneticists’ technology. But, in selectively reading them both, in projecting our own experiences and desires, perhaps we will be able to advance into this darkness where questions point, as timeless as they are modern: what is the power of representation? Does the image succumb to the violence of death, or does it possess the gift of modulating it? By what alchemy of sacrifice is this sacred space constituted, which may be nothing other that our intimate grappling with our passions and our mortality? How did this intimacy come about?

The worship of skulls appeared in the earliest times of humanity, since there is evidence of post mortem decapitation already among the hominids of the Lower Paleolithic (two million to one hundred thousand years before Christ) and the Middle Paleolithic (one hundred thousand to thirty-five thousand years before Christ). During this same period, the head was also a privileged object for ritual or routine cannibalism. Skulls from which the brains had been removed through enlarging the occipital hole were displayed as though for burial at the center of stone circles. Some were decorated; others had undergone manipulations (deformations and trephinations), or else they had been replaced by representations constituting true masterpieces.3

In Europe today, the oldest known human skull, more than three hundred thousand years old, dates from the beginning of the Rissian glaciation. It was found in La Caune de l’Arago cave in Tautavel (Eastern Pyrenees) in 1971. Lacking any decoration, it was nevertheless “worked”: stripped of flesh before being abandoned, the back part having been removed.

From the Upper Paleolithic (about 35,000–9000 BC), skull cults multiplied and became defined: skulls were made into drinking goblets and displayed on stone slabs. During the Mesolithic (about 10,000–6000 BC), skulls were found for the first time amassed in graves and washed in red ochre. But it was not until the Neolithic (7000–4000 BC depending upon the region), with the settling process brought about by agriculture and husbandry, that the first true art objects made from skulls appeared, in the Jordan Valley. Henri Gastaut writes, “The inhabitants of Jericho II, six thousand years before Christ, within the walls of their city, under the floors of their circular houses, kept skulls whose faces were modeled over with plaster, the e...