- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About This Book

Imagine watching an action film in a small-town cinema hall in Bangladesh, and in between the gun battles and fistfights a short pornographic clip appears. This is known as a cut-piece, a strip of locally made celluloid pornography surreptitiously spliced into the reels of action films in Bangladesh. Exploring the shadowy world of these clips and their place in South Asian film culture, Lotte Hoek builds a rare, detailed portrait of the production, consumption, and cinematic pleasures of stray celluloid.

Hoek's innovative ethnography plots the making and reception of Mintu the Murderer (2005, pseud.), a popular, Bangladeshi B-quality action movie and fascinating embodiment of the cut-piece phenomenon. She begins with the early scriptwriting phase and concludes with multiple screenings in remote Bangladeshi cinema halls, following the cut-pieces as they appear and disappear from the film, destabilizing its form, generating controversy, and titillating audiences. Hoek's work shines an unusual light on Bangladesh's state-owned film industry and popular practices of the obscene. She also reframes conceptual approaches to South Asian cinema and film culture, drawing on media anthropology to decode the cultural contradictions of Bangladesh since the 1990s.

Frequently asked questions

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Note on Transliteration, Translation, and Pseudonyms

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Before Mintu the Murderer

- 1. Writing Gaps: The Script of Mintu the Murderer

- 2. A Handheld Camera Twisted Rapidly: The Technology of Mintu the Murderer

- 3. Actress/Character: The Heroines of Mintu the Murderer

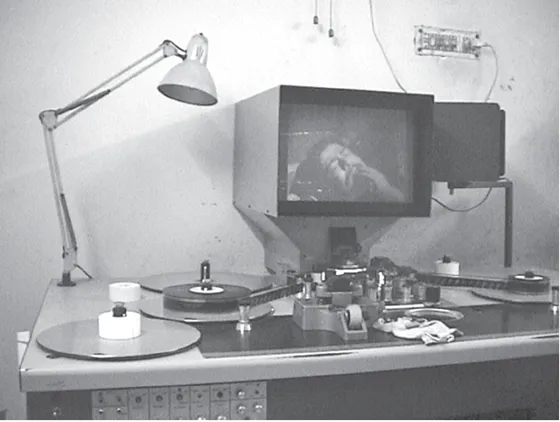

- 4. Cutting and Splicing: The Editor and Censor of Mintu the Murderer

- 5. Noise: The Public Sphere of Mintu the Murderer

- 6. Unstable Celluloid: The Exhibition of Mintu the Murderer

- Conclusion: After Mintu the Murderer

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series List