![]()

PART ONE

___

HISTORY

![]()

THE MAKING AND REMAKINGS OF AN AMERICAN ICON

‘Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima’ from Photojournalism to Global, Digital Media

___

METTE MORTENSEN

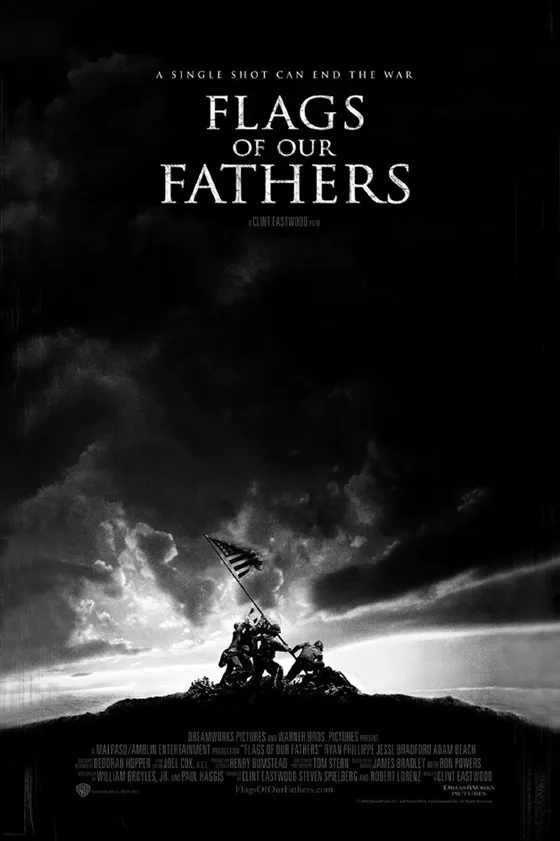

On the poster for Clint Eastwood’s 2006 movie Flags of Our Fathers we see the allegedly most extensively reproduced icon in American popular culture, Joe Rosenthal’s Pulitzer Prize-winning image from February 1945 of United States Marines raising ‘Old Glory’ atop Mount Suribachi on the Japanese volcano island Iwo Jima. ‘A single shot can end the war,’ the poster’s tagline says. This is a pun. In the context of a war movie, ‘shot’ would normally be associated with a gunshot. Here, however, it also refers to a photographic ‘shot’ or ‘snapshot’, namely the prominent picture taken by Rosenthal. With this wordplay on the double meaning of ‘shot’, the tagline highlights one of the key points of the film. Photography is a powerful weapon in modern warfare. Or, to put it in the words of Joe Rosenthal’s character in the film: ‘The right picture can win or lose a war.’

The Iwo Jima photograph has remained in the public eye for well over half a century. As an ever-powerful symbol of heroism, patriotism, and unity in the collective memory, it is re-circulated to meet ideological, political, or commercial ends or simply to entertain. This chapter is going to pursue the argument that ‘Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima’, as the photograph is officially called, has been mobilised in various historical settings to justify state action and win the support of the home front for the foreign policy. As the then Vice President Richard Nixon declared at the ceremony for the erection of the Marine Corps War Memorial in 1954, the motif ‘symbolizes the hopes and dreams of America and the real purpose of our foreign policy’ (Marling and Wetenhall 1991: 17).

The flag raising scene from Joe Rosenthal’s photograph taken February 23, 1945 on Iwo Jima, as the image on the poster for Clint Eastwood’s Flags of Our Fathers (2006).

Even if it sounds like a washed-out cliché to call the Iwo Jima picture an icon, we have yet to take a step back and explore the full implications of that label. The ambition of this chapter is to address the fundamental questions: What power lies in the dissemination, mobilisation, and mass consumption of photographic icons? And, moreover, which historical changes have these mechanisms undergone from the photojournalism of World War II to the digital, global media of today?

As is characteristic of icons, the photo has a long history of ‘referential slippage’ prompted by political interests and strategic manoeuvres (Hariman and Lucaites 2007: 105). When circulated in the mass media, a shift occurs from the photograph’s referential meaning to its symbolic meaning, that is, from the original intention and historical circumstances to projected values such as fellowship, conquest, and victory. As John Hariman and Robert Louis Lucaites point out in No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture and Liberal Democracy (2007), the image may foster a sense of cultural and political continuity, yet it does not convey a fixed message apprehended by spectators across time and place (Hariman and Lucaites 2007: 111). Rather, an icon seems to contain a universal message while in effect giving way to situated identifications that employ its historical background as an interpretive framework to legitimise current political beliefs and calls for action.

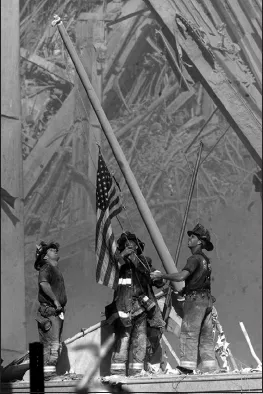

The firefighters planting the flag ‘Iwo Jima style’ in the ruins of the World Trade Center in Thomas E. Franklin’s photograph ‘Ground Zero Spirit’ (2001).

Three appropriations of the landmark motif, from as many continents, will be examined in this chapter. The first appropriation is the story told in Flags of Our Fathers, of how the referential slippage takes place instantly due to a demand for iconic images to unite the nation in the last months of World War II and raise money for the continued war effort. The second example is Thomas E. Franklin’s image of three firefighters planting the American flag ‘Iwo Jima style’ on the ruins of the World Trade Center (Willis 2002: 276). Finally, a video from 2007 created by Danish soldiers during their service in Afghanistan will serve as an example of how the tableau has entered into the popular iconography of the ‘War on Terror’.

A MOUNTAIN OF CASH

‘A chance shot turned an unremarkable act into a remarkable photograph’ (Bradley and Powers 2006: 258). In this way, James Bradley, son of flag raiser John ‘Doc’ Bradley, sums up the legacy of the Iwo Jima photo in his bestselling book Flags of Our Fathers (2000), upon which Eastwood’s film is based.

Repeatedly Joe Rosenthal of the Associated Press has been met with the accusation that ‘Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima’ is staged. The persistent, albeit unjust, rumours are spurred on mainly by the confusion over the scene immortalised by Rosenthal being actually the second planting of the American flag on the strategically important Mount Suribachi.1 The photographer for Leatherneck, Lou Lowery, recorded the first flag raising, yet the Marine magazine withheld the series so as not to compete with Rosenthal’s photo, which soon became the official documentation of the event (Marling and Wetenhall 1991: 61). Similarly, the original flag raisers received neither public nor military recognition until much later, even though they had secured a vital enemy installation, whereas the replacement flag was only of symbolic importance (Marling and Wetenhall 1991: 87).

Rosenthal seized the opportunity to shoot his celebrated picture when later on the same day, 23 February 1945, the second flag was raised because the Secretary of the Navy wanted the first flag as his souvenir and, the Secretary claimed, so that a larger flag would be visible from all over the island. According to Rosenthal, he was unsure how the random snapshot would turn out. However, when he sent off the negative for processing, the image almost assumed a life of its own. Two days later it cleared the front page of the New York Times and 200 other Sunday papers. Some 137 million postage stamps were issued, selling 3 million copies on the first day alone (Baudry 2007: 19). As early as March 1945, congress decided to adopt the image as the logo for the Seventh War Loan Drive and hire the three surviving men of the six in the photo, James ‘Doc’ Bradley, Rene Gagnon, and Ira Hayes, as the star attractions of the tour, raising an unparalleled $26.3 billion for the war effort in three months. On occasion of the bond drive, the photo was printed on no less than 3.5 million colour posters as well as some 15,000 billboards and 175,000 cards to be placed on streetcars and buses. The picture also formed the basis of Allan Dwan’s Sands of Iwo Jima from 1949, starring John Wayne along with Bradley, Gagnon, and Hayes, who briefly re-enact the celebrated scene with the actual flag from Iwo Jima. And not least, the Marine Corps War Memorial created by artist Felix de Weldron was erected in 1954, which was based on Rosenthal’s picture. Since then, the victorious image has been reprinted on commemorative plates, woodcuttings, key chains, cigarette lighters, matchbook covers, beer steins, lunch boxes, hats, T-shirts, calendars, credit cards, trading cards, postcards, stick-on tattoos, and other merchandise.

The photo most likely became so tremendously popular because after more than three years of war the American public craved to hear that victory was at hand, and to feel the sense of national unity expressed in the bond tour’s catchphrase ‘Now all together’. Photographic icons tell people what they know already or what they would like to be told. Like other canonical wartime icons, the photo triggers an emotional response in confirming and strengthening the predominant beliefs, hopes, and sentiments about the war. The government capitalised on these emotions to convince the population to buy war bonds; as President Truman says in the film: ‘You fought for a mountain in the Pacific, now you need to fight for a mountain of cash.’ From the outset, political agendas went hand in hand with popular culture in the reception of the picture.

WHAT IS AN ICON?

‘Plenty of other pictures were taken that day but none anybody wanted to see. What we see and do in war. The cruelty … it’s unbelievable. But somehow we gotta make some sense of it. To do that we need an easy-to-understand truth and damn few words.’

In this manner the character of Joe Rosenthal, played by Ned Eisenberg, introduces the major conflict of Flags of Our Fathers in the beginning of the movie. This is the split between on the one hand the complex brutality of war and on the other hand the clear-cut, legible pictures offering the home front a symbolic understanding of the combat zone. Icons create an ‘illusion of consensus’, as Susan Sontag phrases it (Sontag 2003: 5). They address a political and national unity as if it can be taken for granted, although they are themselves instrumental in creating that unity. Particularly when political and economic interests orchestrate the writing of history with icons, they are unlikely to offer a visual entrance to a more profound understanding of war, but rather may block that very same entrance with one-dimensional and schematic depictions.

As Flags of Our Fathers compellingly exhibits, icons are powerful in their symbolic references to shared myths and values that endow them with local, national, or even worldwide significance. To quote photography critic Vicki Goldberg, ‘they concentrate the hopes and fears of millions and provide an instant and effortless connection to some deeply meaningful moment in history’ (1991: 135). Photographic icons claim to compress complex phenomena and represent history in exemplary form. They are objects of powerful emotional identification; yet the response to icons is never limited to one single emotion (Hariman and Lucaites 2007: 114). Instead, they activate an open and expansive public emotionality. In the case of Rosenthal’s image, it ranges from hope over nostalgia and sentimentalism to patriotism and protectionism, just as it may trigger the very negation of these emotions, for instance anti-patriotism and antagonism.

Used to refer equally to pop stars, bestselling brands, and religious imagery, the notion of an ‘icon’ has become a favourite popular culture, marketing, and art history term to describe familiar, mass-produced pictures that make first the front pages and, in time, the history books. In order to escape the indiscriminate use of the word, it is beneficial to use German historian Cornelia Brink’s definition of secular icons in her article ‘Secular Icons: Looking at Photographs from Nazi Concentration Camps’, from 2000. According to Brink, secular icons share four qualities with religious cult images: 1) authenticity, 2) symbolicity, 3) canonisation, and 4) a simultaneous showing and veiling of reality (Brink 2000: 135–50). Brink’s theory may shed new light on Flags of Our Fathers, since the intricate role pictures play in warfare is determined by the mechanisms of iconisation, even though this is scarcely acknowledged in the international literature on war and the media.

First, the importance attributed to ‘authenticity’ can hardly be exaggerated. Authenticity not only addresses the basic question of whether the picture is true or manipulated. The concept is intimately connected with war photography, and the photographic medium as such. Since their subtext is the risk of death for both the subjects and the photographer, war photographs make an urgent claim to our attention and are often believed to touch us more directly and deeply than most other genres (Brothers 1997: xi). Furthermore, photographs bear a close and, to borrow a semiotic term from Charles S. Peirce (1965: 143–44; 156–73), indexical relation to reality. Although they easily acquire a symbolic meaning, photographs can never be merely symbolic, since their subject is represented specifically and intensely in time as well as in space. ‘Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima’ purveys the impression of visual transparency, with the six men seemingly unaware of the camera and unconscious of their own appearance. In the place of the triumphant trophy shot possibly to be expected of this event, they are caught in the course of action, and the raising of the American flag is performatively to be completed over and over again in the viewers’ imagination.2

Finally, to accentuate an overlooked point, as a tool for visual persuasion icons are able to move on and bestow new frameworks, stories, and agendas with authenticity. One of the greatest powers as well as one of the lurking dangers of icons is their capacity to authorise diverse ideologies and political standpoints. If there is no connection between the new context and the original one, the icon readily fills in as the missing link and may, for example, sanction the gloating self-image of Danish soldiers posted in Afghanistan, to which I shall return in the last section.

This leads us to the second characteristic of icons, symbolicity. Why is it, to use another line from Rosenthal in Flags of Our Fathers, that ‘everybody saw that damn picture and made up their own story about it’? To cut a long answer short, semantic openness and emotional appeal comprise the successful formula behind the photo’s symbolic power. The six bodies are in harmony, knees moving together as if marching in step. No one stands out, no individual traits are show, no ranks are visible. Even if Rosenthal’s character in the film regrets that the Marines’ faces are not distinguishable, this has most likely boosted the popularity of the photo, because the figures may stand for all Marines – and have actually come to stand for all Marines, with the Marine Corps Memorial dedicated to fallen Marines from 1775 to the present day. Since the image does not offer any facial clues as to what might constitute an appropriate response, the six men become blanks that national sentiments and governmental and military interests might be projected onto.

Likewise, the empty sky and the featureless island are left open to projections. From conquering the wilderness to the 1969 moon landing, flag raisings in a vast and bare landscape make up an often-repeated motif in American popular culture, as also discussed by Robert Eberwein in his ‘Following the Flag in the American Film’ in this anthology. With its idealised, decontextualised battlefield, the image alludes to the utopia of making a new start after successfully winning over enemy fortifications that goes back to the first settlers on the North American continent.

The third characteristic of secular icons is canonisation, or the process by which wide circulation elevates certain images to objects of veneration and intense emotional identification for the...