![]()

PART ONE

Why Civil Resistance Works

![]()

CHAPTER ONE THE SUCCESS OF NONVIOLENT RESISTANCE CAMPAIGNS

Nonviolence is fine as long as it works.

MALCOLM X

IN NOVEMBER 1975, Indonesian president Suharto ordered a full-scale invasion of East Timor, claiming that the left-leaning nationalist group that had declared independence for East Timor a month earlier, the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (Fretilin), was a communist threat to the region. Fretilin’s armed wing, the Forças Armadas de Libertação Nacional de Timor-Leste (Falintil), led the early resistance to Indonesian occupation forces in the form of conventional and guerrilla warfare. Using weapons left behind by Portuguese troops,1 Falintil forces waged armed struggle from East Timor’s mountainous jungle region. But Falintil would not win the day. Despite some early successes, by 1980 Indonesia’s brutal counterinsurgency campaign had decimated the armed resistance along with nearly one third of the East Timorese population.2

Yet nearly two decades later, a nonviolent resistance movement helped to successfully remove Indonesian troops from East Timor and win independence for the annexed territory. The Clandestine Front, an organization originally envisaged as a support network for the armed movement, eventually reversed roles and became the driving force behind the nonviolent, pro-independence resistance. Beginning in 1988, the Clandestine Front, which grew out of an East Timorese youth movement, developed a large decentralized network of activists, who planned and executed various nonviolent campaigns inside East Timor, in Indonesia, and internationally. These included protests timed to the visits of diplomats and dignitaries, sit-ins inside foreign embassies, and international solidarity efforts that reinforced Timorese-led nonviolent activism.

The Indonesian regime repressed this movement, following its standard approach to violent and nonviolent challengers from within. But this repression backfired. Following the deaths of more than two hundred East Timorese nonviolent protestors at the hands of Indonesian troops in Dili in November 1991, the pro-independence campaign experienced a major turning point. The massacre, which was captured on film by a British cameraman, was quickly broadcast around the world, causing international outrage and prompting the East Timorese to rethink their strategy (Kohen 1999; Martin, Varney, and Vickers 2001). Intensifying nonviolent protests and moving the resistance into Indonesia proper became major components of the new strategy.

Suharto was ousted in 1998 after an economic crisis and mass popular uprising, and Indonesia’s new leader, B. J. Habibie, quickly pushed through a series of political and economic reforms designed to restore stability and international credibility to the country. There was tremendous international pressure on Habibie to resolve the East Timor issue, which had become a diplomatic embarrassment, not to mention a huge drain on Indonesia’s budget. During a 1999 referendum, almost 80 percent of East Timorese voters opted for independence. Following the referendum, Indonesianbacked militias launched a scorched-earth campaign that led to mass destruction and displacement. On September 14, 2000, the UN Security Council voted unanimously to authorize an Australian-led international force for East Timor.3

The United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor oversaw a two-year transition period before East Timor became the world’s newest independent state in May 2002 (Martin 2000). Although a small number of Falintil guerrillas (whose targets had been strictly military) kept their weapons until the very end, it was not their violent resistance that liberated the territory from Indonesian occupation. As one Clandestine Front member explained, “The Falintil was an important symbol of resistance and their presence in the mountains helped boost morale, but nonviolent struggle ultimately allowed us to achieve victory. The whole population fought for independence, even Indonesians, and this was decisive.”4

Similarly, in the Philippines in the late 1970s, several revolutionary guerrilla groups were steadily gaining strength. The Communist Party of the Philippines and its New People’s Army (NPA) were inspired by Marxist-Leninist-Maoist ideologies and pursued armed revolution to gain power. State-sponsored military attacks on the NPA dispersed the guerrilla resistance until the NPA encompassed all regions of the country. The Philippine government launched a concerted counterinsurgency effort, and the NPA was never able to achieve power.

In the early 1980s, however, members of the opposition began to pursue a different strategy. In 1985 the reformist opposition united under the banner of UNIDO (United Nationalist Democratic Organization) with Cory Aquino as its presidential candidate. In the period leading up to the elections, Aquino urged nonviolent discipline, making clear that violent attacks against opponents would not be tolerated. Church leaders, similarly, insisted on discipline, while the National Citizens’ Movement for Free Elections trained half a million volunteers to monitor elections.

When Marcos declared himself the winner of the 1986 elections despite the counterclaims of election monitors, Cory Aquino led a rally of 2 million Filipinos, proclaiming victory for herself and “the people.” The day after Marcos’s inauguration, Filipinos participated in a general strike, a boycott of the state media, a massive run on state-controlled banks, a boycott of crony businesses, and other nonviolent activities.

A dissident faction of the military signaled that it favored the opposition in this matter, encouraging the opposition to form a parallel government on February 25 with Aquino at its head. Masses of unarmed Filipino civilians, including nuns and priests, surrounded the barracks where the rebel soldiers were holed up, forming a buffer between those soldiers and those who remained loyal to Marcos. President Ronald Reagan’s administration had grown weary of Marcos and signaled support for the opposition movement. That evening, U.S. military helicopters transported Marcos and his family to Hawaii, where they remained in exile. Although the Philippines has experienced a difficult transition to democracy, the nonviolent campaign successfully removed the Marcos dictatorship. Where violent insurgency had failed only a few years earlier, the People Power movement succeeded.

THE PUZZLE

The preceding narratives reflect both specific and general empirical puzzles. Specifically, we ask why nonviolent resistance has succeeded in some cases where violent resistance had failed in the same states, like the violent and nonviolent pro-independence campaigns in East Timor and regime-change campaigns in the Philippines. We can further ask why nonviolent resistance in some states fails during one period (such as the 1950s Defiance Campaign by antiapartheid activists in South Africa) and then succeeds decades later (such as the antiapartheid struggle in the early 1990s).

These two specific questions underline a more general inquiry, which is the focus of this book. We seek to explain two related phenomena: why nonviolent resistance often succeeds relative to violent resistance, and under what conditions, nonviolent resistance succeeds or fails.5

Indeed, debates about the strategic logic of different methods of traditional and nontraditional warfare have recently become popular among security studies scholars (Abrahms 2006; Arreguín-Toft 2005; Byman and Waxman 1999, 2000; Dashti-Gibson, Davis, and Radcliff 1997; Drury 1998; Horowitz and Reiter 2001; Lyall and Wilson 2009; Merom 2003; Pape 1996, 1997, 2005; Stoker 2007). Implicit in many of these assessments, however, is an assumption that the most forceful, effective means of waging political struggle entails the threat or use of violence. For instance, a prevailing view among political scientists is that opposition movements select terrorism and violent insurgency strategies because such means are more effective than nonviolent strategies at achieving policy goals (Abrahms 2006, 77; Pape 2005). Often violence is viewed as a last resort, or a necessary evil in light of desperate circumstances. Other scholarship focuses on the effectiveness of military power, without comparing it with alternative forms of power (Brooks 2003; Brooks and Stanley 2007; Desch 2008; Johnson and Tierney 2006).

Despite these assumptions, in recent years organized civilian populations have successfully used nonviolent resistance methods, including boycotts, strikes, protests, and organized noncooperation to exact political concessions and challenge entrenched power. To name a few, sustained and systematic nonviolent sanctions have removed autocratic regimes from power in Serbia (2000), Madagascar (2002), Georgia (2003), and Ukraine (2004–2005), after rigged elections; ended a foreign occupation in Lebanon (2005); and forced Nepal’s monarch to make major constitutional concessions (2006). In the first two months of 2011, popular nonviolent uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt removed decades-old regimes from power. As this book goes to press, the prospect of people power transforming the Middle East remains strong.

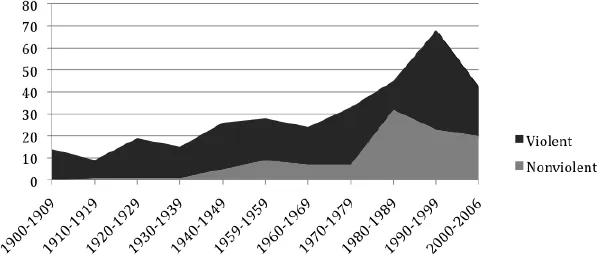

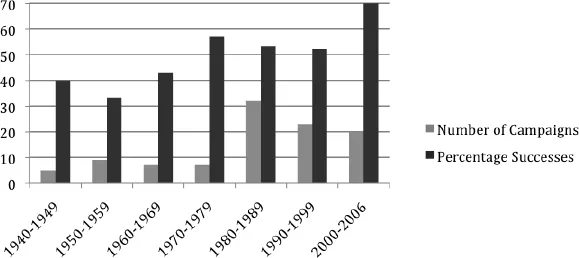

In our Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes (NAVCO) data set, we analyze 323 violent and nonviolent resistance campaigns between 1900 and 2006.6 Among them are over one hundred major nonviolent campaigns since 1900, whose frequency has increased over time. In addition to their growing frequency, the success rates of nonviolent campaigns have increased. How does this compare with violent insurgencies? One might assume that the success rates may have increased among both nonviolent and violent insurgencies. But in our data, we find the opposite: although they persist, the success rates of violent insurgencies have declined.

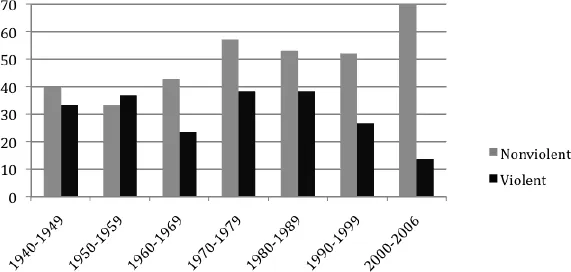

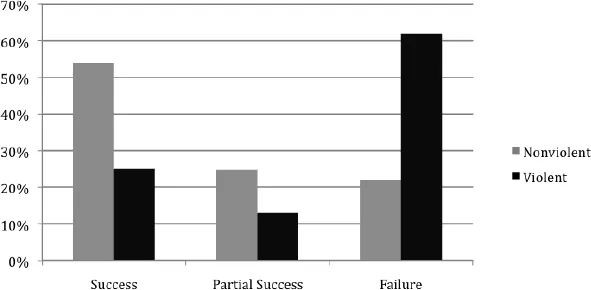

The most striking finding is that between 1900 and 2006, nonviolent resistance campaigns were nearly twice as likely to achieve full or partial success as their violent counterparts. As we discuss in chapter 3, the effects of resistance type on the probability of campaign success are robust even when we take into account potential confounding factors, such as target regime type, repression, and target regime capabilities.7

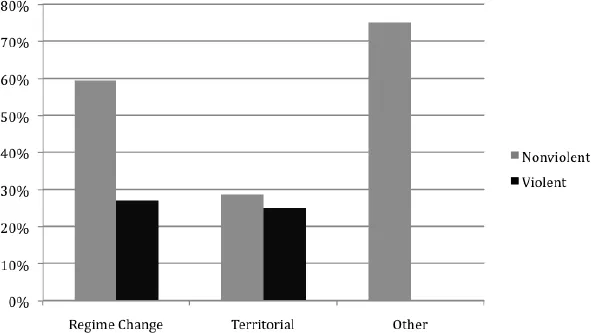

The results begin to differ only when we consider the objectives of the resistance campaigns themselves. Among the 323 campaigns, in the case of antiregime resistance campaigns, the use of a nonviolent strategy has greatly enhanced the likelihood of success. Among campaigns with territorial objectives, like antioccupation or self-determination, nonviolent campaigns also have a slight advantage. Among the few cases of major resistance that do not fall into either category (antiapartheid campaigns, for instance), nonviolent resistance has had the monopoly on success.

The only exception is that nonviolent resistance leads to successful secession less often than violent insurgency. Although no nonviolent secession campaigns have succeeded, only four of the forty-one violent secession campaigns have done so (less than 10 percent), also an unimpressive figure. The implication is that campaigns seeking secession are highly unlikely to succeed regardless of whether they employ nonviolent or violent tactics. We explore various factors that could influence these results in chapter 3. It is evident, however, that especially among campaigns seeking regime change or liberation from foreign occupation, nonviolent resistance has been strategically superior. The success of these nonviolent campaigns—especially in light of the enduring violent insurgencies occurring in many of the same countries—begs systematic exploration.

FIGURE 1.1 FREQUENCY OF NONVIOLENT AND VIOLENT CAMPAIGN END YEARS

FIGURE 1.2 NUMBER OF NONVIOLENT CAMPAIGNS AND PERCENTAGE OF SUCCESSES, 1940–2006

FIGURE 1.3 SUCCESS RATES BY DECADE, 1940–2006

FIGURE 1.4 RATES OF SUCCESS, PARTIAL SUCCESS, AND FAILURE

FIGURE 1.5 SUCCESS RATES BY CAMPAIGN OBJECTIVE

This book investigates the reasons why—in spite of conventional wisdom to the contrary—civil resistance campaigns have been so effective compared with their violent counterparts. We also consider the reasons why some nonviolent campaigns have failed to achieve their stated aims, and the reasons why violent insurgencies sometimes succeed.

THE ARGUMENT

Our central contention is that nonviolent campaigns have a participation advantage over violent insurgencies, which is an important factor in determining campaign outcomes. The moral, physical, informational, and commitment barriers to participation are much lower for nonviolent resistance than for violent insurgency. Higher levels of participation contribute to a number of mechanisms necessary for success, including enhanced resilience, higher probabilities of tactical innovation, expanded civic disruption (thereby raising the costs to the regime of maintaining the status quo), and loyalty shifts involving the opponent’s erstwhile supporters, including members of the security forces. Mobilization among local supporters is a more reliable source of power than the support of external allies, which many violent campaigns must obtain to compensate for their lack of participants.

Moreover, we find that the transitions that occur in the wake of successful nonviolent resistance movements create much more durable and internally peaceful democracies than transitions provoked by violent insurgencies. On the whole, nonviolent resistance campaigns are more effective in getting results and, once they have succeeded, more likely to establish democratic regimes with a lower probability of a relapse into civil war.

Nestling our argument between literatures on asymmetrical warfare, contentious politics, and strategic nonviolent action, we explain the relative effectiveness of nonviolent resistance in the following way: nonviolent campaigns facilitate the active participation of many more people than violent campaigns, thereby broadening the base of resistance and raising the costs to opponents of maintaining the status quo. The mass civilian participation in a nonviolent campaign is more likely to backfire in the face of repression, encourage loyalty shifts among regime supporters, and provide resistance leaders with a more diverse menu of tactical and strategic choices. To regime elites, those engaged in civil resistance are more likely to appear as credible negotiating partners than are violent insurgents, thereby increasing the chance of winning concessions.

However, we also know that resistance campaigns are not guaranteed to succeed simply because they are nonviolent. One in four nonviolent campaigns since 1900 was a total failure. In short, we argue that nonviolent campaigns fail to achieve their objectives when they are unable to overcome the challenge of participation, when they fail to recruit a robust, diverse, and broad-based membership that can erode the power base of the adversary and maintain resilience in the face of repression.

Moreover, more than one in four violent campaigns has succeeded. We briefly investigate the question of why violent campaigns sometimes succeed. Whereas the success of nonviolent campaigns tends to rely more heavily on local factors, violent insurgencies tend to succeed when they achieve external support or when they feature a central characteristic of successful nonviolent campaigns, which is mass popular support. The presence of an external sponsor combined with a weak or predatory regime adversary may enhance the credibility of violent insurgencies, which may threaten the opponent regime. The credibility gained through external support may also increase the appeal to potential recruits, thereby allowing insurgencies to mobilize more participants against the opponent. International support is, however, a double-edged sword. Foreign-state sponsors can be fickle and unreliable allies, and state sponsorship can produce a lack of discipline among insurgents and exacerbate free rider problems (Bob 2005; Byman 2005).

THE EVIDENCE

We bring to bear several different types of evidence to support our argument, including statistical evidence from the NAVCO data set and qualitative evidence ...