![]() FIRST PERSON SINGULAR

FIRST PERSON SINGULAR![]()

The Role of History in the Individual: Working Notes for a Film

Michael Chanan

It follows, then, that by virtue of particular traits of their character individuals can influence the fate of society. Sometimes this influence is very considerable; but the possibility of exercising this influence, and its extent, are determined by the form of organisation of society, by the relation of forces within it. The character of an individual is a ‘factor’ in social development only where, when, and to the extent that social relations permit it to be such.

Georgi Plekhanov, ‘The Role of the Individual in History’ (1898/1940: 41)

1

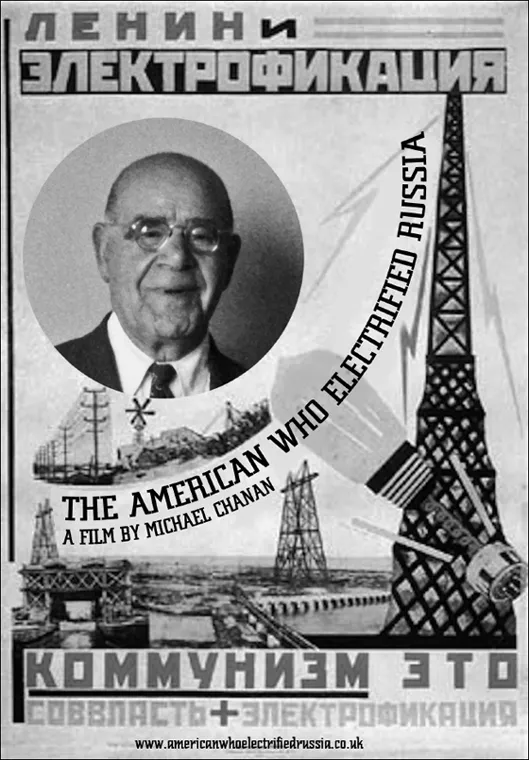

The film archives are full of neglected newsreels and documentaries, fragmentary traces serving as signs of what is mostly forgotten – moments robbed from history, briefly exhibited, and then, except for a few iconic examples, relegated to the shelves and catalogues. This field of the semiosis of the historical trace is the terrain of the film that occasions these notes, which were drafted while the film was being made, and completed after the editing was finished. The American Who Electrified Russia is about the role of an individual in history, but also of history in the individual – a biographical investigation of my maternal grandmother’s cousin, Solomon Abramovich Trone (1872–1969). Walter Benjamin spoke of ‘the enigmatic question of the nature of human existence as such, but also of the biographical historicity of the individual’ (1977: 166). To recount this biography, the film constructs a dialogue between family memory and the archive, both public and private, with their photographs and films, documents and mementos, and discovers that there are gaps between them. I guessed this would happen, and from the outset wanted to make a film which foregrounded the problems by presenting the process of investigation, and not just the results.

Poster based on Soviet original

Trone’s life was intertwined with History, but in a paradoxical fashion. A participant in the revolutions of 1905 and 1917, he was an electrical engineer who became a director at General Electric (GE), the foremost American corporation of its day, and thus, although unrecorded in the history books, a key figure in the electrification of the Soviet Union. In 1928, when GE became the first American corporation to sign a contract with the Bolsheviks, the signatory on behalf of GE was Trone, who himself was closely involved in the technical design of projects like the Dnepr Dam. Later, after retiring from GE, he worked as an industrial adviser in China, India and Israel. In 1940, he helped to rescue Jewish refugees from Nazism; five years later, he was appointed to the Allied Reparations Commission, which reported to the Potsdam Conference at the end of the war. Ironically I owe my good fortune that he came to live in London when I was growing up to Senator McCarthy and American paranoia about Communism. Trone had gone to live in the USA in 1916, giving up his membership of the Bolshevik Party, and later becoming an American citizen; when they took away his passport in 1953 he found himself on a visit to London, and decided to stay; otherwise I would probably not now be telling his story.

The film will recuperate forgotten history, but the first thing I know I have to accept, because this is a family film, is that in order to make it, I have to be in it. I cannot avoid it becoming a first person film, in which I participate along with my cousin, Trone’s daughter Sasha, and other family members, in front of the camera – which is something I have never desired. When I started out in the early 1970s, by making a pair of films on contemporary music for BBC2, I readily adopted the mode of the television arts documentary, or at least that version of the genre that took the form of the filmic essay. Loosely defined, this is a mode of documentary which encourages stylistic experiment, and while the camera focusses on the character and personality of the subject, the filmmaker is present through the ‘voice’ of the film; it was often introduced by the programme anchor as ‘a personal viewpoint’. Within this format, I didn’t mind being heard interacting with my subjects on the soundtrack, but preferred not to be seen, and I have pretty much stuck with this since. This time is going to be different: an historical essay and first person family film combined.

2

The filmic essay is loosely defined – because there is no tighter way to define it. The essay film is not a genre in the normal sense, built out of a permutation of a certain repertoire of features. With my theoretical cap on, I have long believed that this is anyway not a very good way to approach the nature of genre, which in practice is always, as Mikhail Bakhtin demonstrated throughout his work, much more fluid and porous than logical definitions seem to suppose. This is especially true in the case of the documentary, of which Joris Ivens somewhere wrote that it constitutes a ‘creative no-man’s land’, like an interloper in the genre system. Even more so in the case of the essay film, which can easily use any of the means and practices employed in any other mode of documentary filming.

Precisely the way the most disparate material gels into a narrative, a tale, or an argument, is the locus of the film’s ‘voice’, which is thus, in part, a structuring absence (one reason it is so difficult to define). The institutional form of documentary, produced by or made for television, is the same, but here (except for zones of greater freedom like arts programming) the director has abdicated the authorial position in favour of the formulaic requirement of the slot, the schedules, the pretence of ‘balance’, the channel controller’s prejudices and whims. The personal point of view of the essay here dissolves into an ideological soup. Nevertheless, if we are going to talk sensibly about the essay film, there is no point in restricting its varieties by arbitrarily limiting its criteria.

Of course, in working for television, I’d accepted that films had to have commentaries – it was part of the deal – but I grew to strongly dislike them. Especially after the experience of a piece of current affairs reportage on human rights in Cuba (Cuba From Inside, ‘Dispatches’, Channel Four, 1988) where the house style not only required a tight journalistic commentary but wall-to-wall speech, with no space for the pictures to breathe. In contrast, in classic documentaries by the likes of Joris Ivens, Georges Franju, Alain Resnais and Chris Marker, the film is visually led, and the spoken voiceover is a vehicle for essayistic and even poetic rumination. But these films rarely turn up in the canons of documentary recognised by the television professionals. (They belong to the art-house, and are only now beginning to come back into circulation on DVD, sometimes as supplementary ‘extras’ to a feature film.) Marker is a curious exception, because he moved his medium from film to video to multimedia, leaving much of his previous work by the wayside, where sadly it mostly remains (but the titles, including Letter from Siberia, 1957, and Le Joli Mai, 1963, are legendary). His commentaries for films by others – Resnais, Ivens – are already remarkable for their rich juxtaposition of verbal with visual imagery, or in Bakhtin’s word, their dialogical texture. In later films of his own, like Sans Soleil (1983), this can no longer be called commentary – it is the very embodiment of the filmmaker speaking through voices, and a paradigm for the whole tradition of expanded cinema, avant-garde or experimental film and video, call it what you will, from the 1960s until today.

Television is exactly the opposite. It turns the use of commentary into a lazy way of making films, with the result that many of them become little more than illustrated radio programmes, nowadays with a dizzying dose of digital graphics. Nevertheless, they are still essay films, but in a mechanical and schematic register. Subject to external requirements like commercial breaks, the commentary keeps going back over the ground after each break before moving on, like a model school essay. Often informative, they remain rather shallow. (This is even nowadays true of science films, which demand a certain rigour, but if one compares the BBC’s Horizon series today with thirty years ago, there’s been some dumbing down.) If this is the result of television’s quasi-industrial and increasingly managerialist mode of production, the model is nowadays only broken in individually crafted films by the likes of Adam Curtis, or the poet Tony Harrison, who demonstrate the imaginative use of the medium to develop a much more personal, potent and disturbing essayistic style.

Another mode of the essayistic comes to the fore in one of the dominant forms of television documentary, the presenter-led, which casts a high-profile figure from journalism or academia – such as John Pilger or Simon Schama – in the role of reporter or presenter. The formula here is the illustrated discourse written and delivered by the telegenic talent in ever-changing locations, manoeuvred by a director whose essential function is the technical one of devising the visual treatment. When it comes to sober and serious subjects like civilisation and history, then from Kenneth Clark to Niall Ferguson, what we get is the authoritative version of the mandarin class. The visual style is determined by the producer and director on duty but the personality on screen displaces the director as author of the film, the camera is turned into the talent’s inevitable appendage, and generally reduced to an instrument to illustrate the verbal discourse. The image is dominated by the word in a regression to the didactic style of institutional documentary before the arrival of synchronous sound filming around the end of the 1950s.

Nowadays, of course, with the agility of video, there is an alternative, in which the directorial author takes their revenge by stepping into the role of the talent – I refer to names like Marcel Ophuls, Nick Broomfield, Michael Moore – reasserting authorship in a form that is both performative and folds back into the primacy of the camera itself as both witness and agent provocateur (capacities originally developed by cinéma vérité and direct cinema in the 1960s). Ophuls is the paradigm of the sober but ironic social commentator, in contrast to the buffoonery of Broomfield or Moore. A variant is found in Molly Dineen, who plays an invisible performative role from behind her own camera; as a result, her presence is constantly seen in the return glance of the person she’s talking to, ingrained in the picture, but her voice is gentle, intensely inquisitive, and without a trace of the macho confrontation.

Except perhaps for the last, these models were not available to me when I returned to filmmaking ten years ago, after a decade teaching and writing. They were either unappealing, or else demanded more resources than I could lay my hands on within academia. What interested me was taking advantage within the academic arena of the potential of low-budget digital video to make films of ideas. This I proceeded to do in two ways. First, with some short scratch videos, made to be shown at conferences instead of presenting a paper, and thus a maximum of twenty minutes long. These were made entirely from found material, some of it my own, and dealt with topics like 9/11, orchestras and conductors, and film music. Second, long films, where I could explore the theme of a film through dialogue with different interlocutors. The first of these was solitary work, but very fast and mostly intuitive; this was Human Wrongs (2001). The second, Detroit: Ruin of a City (2005), was extended and planned (although only loosely – we’re talking documentary here, which always has to respond to the unforeseen). It also employed a new form of collaboration to replace the dialogue that goes on within the traditional documentary crew.

In Human Wrongs, the theme is human rights, and the dialogue is with the writer Ariel Dorfman, as he participates in a series of events in Washington. The subject was his own idea, and he approved the edit but was not involved in it. In Detroit: Ruin of a City, about the rise and fall of the Motor City, the main interlocutor is the sociologist George Steinmetz from the nearby University of Michigan, who converses on screen with a range of characters including myself behind the camera. In neither film do I appear in front of camera, since in both cases I am shooting the film myself. The first is a straightforward director/cameraman film, enlivened by Ariel’s direct address to the camera. For the second we found a different strategy, that of co-authorship from start to finish. The film is both an historical essay and a city film, but instead of a scripted commentary, we hit on the device of filming our conversation as we were making the film; but still I stayed off camera.

With The American Who Electrified Russia, however, I knew from the start that I couldn’t remain unseen: if this was to be truly a family film, I had to be located within the family willy-nilly, and it would inevitably become a first person film. (I even in the end allowed myself to include three photographs of me as a boy.) But in order properly to succeed as a family film, it would have to be the first person plural of the family, speaking among ourselves, our own interlocutors. It had to represent the varied memories and various points of view, as well as the ambiguities and the gaps in our individual and collective knowledge, without unduly privileging anyone – except Trone’s daughter, my cousin Sasha. (I remember thinking: how to construct this first person plural made up of multiple voices? I decided to film spon...