![]()

“UGLY” EXCESS IN ALINE KOMINSKY-CRUMB

The texts I analyze in this chapter, on Aline Kominsky-Crumb, and the next, on Phoebe Gloeckner, deal explicitly with issues of sexual politics. While explorations of sexual and childhood trauma are typically relegated to silence and invisibility, their relevance understood as restricted to the purview of the private sphere, the work of Kominsky-Crumb and Gloeckner responds to this problem by inventing new textual modes of expressing life stories. Kominsky-Crumb, who has a style of hyperexaggerated impressionism, and Gloeckner, who is a trained medical illustrator and favors a viscerally disturbing, provocative style of realism, present images of pleasure and pain that are not found anywhere else in political and accessible cultural production. Their images are challenging not only because, as with Spiegelman and Sacco, they can be confrontational—both authors’ work has been labeled “pornographic,” an accusation complicated by the very idea that they are re-presenting their own experiences of abuse—but also because they are ambivalent: they refuse to ignore the complex terrain of lived sexuality that includes both disgust and titillation. Kominsky-Crumb and Gloeckner erase the inscription of women in the personal space of sexual trauma, offering nuanced representations that place pressure on notions of what a “correct” feminist sexual politics should look like. While their texts demonstrate the affective power of the visual—and suggest that trauma breaks the boundaries of form—they further place themselves in feminist political debates, as with Marjane Satrapi and Lynda Barry, by emphasizing the ordinariness of their narratives: while Kominsky-Crumb links a range of sexual activity, from the traumatizing to the pleasurable, to the everyday, Gloeckner furnishes the titles of her two books, which present both abuse and sexual desire, with the departicularized titles A Child’s Life (1998) and The Diary of a Teenage Girl (2002).

As one of the pioneers of autobiographical comics, and specifically, as the originator, in the early 1970s, of women’s autobiographical comics, Aline Kominsky-Crumb’s voice and style inspired numerous cartoonists—including three whose work I explore in this book: Gloeckner, Barry, and Alison Bechdel. Barry specifically praises Kominsky-Crumb for providing “this perspective on being female that’s not ‘one woman’s lonely struggle.’ . . . Usually, if you see a depiction of what it’s like to be a woman, you see ‘strength’ and no sexual desire.” Crucially, Barry claims this move as particular to the nonesoteric and yet permissive space of comics: “That’s one thing about cartooning [we have] that you don’t see a whole lot of in society” (Powers, “Lynda Barry” 75). In a similar vein, emphasizing sexual expression, Bechdel comments, referring to Kominsky-Crumb’s collaborative comics with her husband, Robert Crumb: “they’re very much an inspiration in terms of trying to be as honest as I can, especially about sexual stuff” (Chute, “An Interview” 1012).1 Kominsky-Crumb consistently presents us with her “secret” and unruly fantasies; she tells us and shows us the “taboo”—for instance, that “confidentially speaking,” as she writes, she enjoys violent sex (Complete Dirty Laundry 49). Kominsky-Crumb’s political project is to visualize how sexuality, even when disruptive, does not have to be turned over to the gaze of the other. Peopled by “excessive” bodies, her so-called uncivilized work, which disrupts a masculinist economy of knowledge production, demonstrates that a crucial part of the struggle to represent the realities of gender beyond sexual difference involves our writing—and drawing—aesthetic elaborations of different ways of being with our sexuality.2 It is important that Kominsky-Crumb acknowledges both enjoyment and shame; her work does not simply celebrate transgression. In admitting to shame, and visually and verbally detailing it along with joy, Kominsky-Crumb, as with figures such as Silvan Tomkins, suggests shame (or what she calls humiliation or “yumiliation”) as productive.3

Largely, readers find Kominsky-Crumb’s work off-putting: for cartoonists, this is because of her excessively “primitive” style; for some feminists, this is because the sexually explicit content of her work not only depicts the character Aline’s body—excrement, blood, and vaginal discharge—intimately but also depicts her enjoying “perverse” or “eccentric” sex (in which, for instance, her husband penetrates her vaginally while grinding her face in vomit). Kominsky-Crumb’s uninhibited representations of her own forceful sexuality in a light that is not always palatable, or favorable, make her a pioneering—if underrecognized—figure in the broad world of feminist visual culture. Yet there is virtually no academic criticism of her work and little more in mainstream literary and art journalism.4 Given that Kominsky-Crumb has been writing the darker side of (her own) female sexuality for almost four decades, it is no surprise that her work is neglected—her underwhelming reception contrasts markedly to that of her husband, cartoonist Robert Crumb, who has been canonized exactly for writing the darker side of (his own) tortured male sexuality.

But while we may understand the double standard as culturally typical, the case of the Crumb family is possibly the defining example of this double standard at work. Crumb is the world’s most famous living cartoonist; art critic Robert Hughes, comparing him to Brueghel and Goya, calls him one of the most important artists of the twentieth-century. Kominsky-Crumb, on the other hand, is almost completely neglected as a cartoonist. In the textual, “conversation”-form introduction to The Complete Dirty Laundry Comics (1993), a book collection of the couple’s collaborative comic strips, Kominsky-Crumb tells her husband: “At least you’re famous and considered a great artist and cultural icon. . . . Look at me, twenty years later and still nobody’s heard o’me” (3).5 This predicament brings to mind the Guerrilla Girls’ famous poster (“public service message”) listing the advantages of being a woman artist, one of which is: “Not having to undergo the embarrassment of being called a genius” (Guerrilla Girls 9).

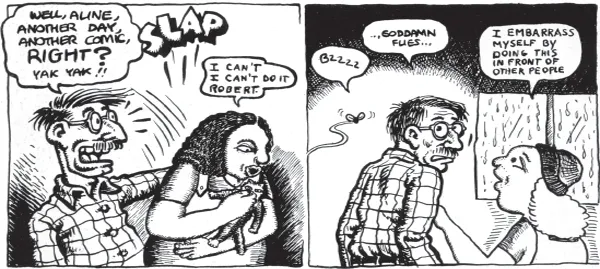

When she first started collaborating with Crumb in the early 1970s on Dirty Laundry Comics, Kominsky-Crumb’s presence on the page—they each drew themselves—inspired ugly responses from some members of Crumb’s underground fan base, who were appalled by her divergence from his more practiced-looking style: “She may be a good lay but keep her off the fucking page,” was typical of the angry letters Crumb received, he reports. “It energized me to think of those fuming twerps wringing their sweaty palms in disgust when they had to look at my tortured scratching next to your fine rendering,” Kominsky-Crumb cheerfully remarks in the aforementioned introduction (Dirty 4). Kominsky-Crumb’s distinctive style, as I will shortly further discuss, provokes because of its messy, “untutored” appearance. She has a thin, wavering line, and her panels, while much of the drawing lacks realistic detail, are regularly crammed and crowded, often lacking “artful” composition and “correct” spatial perspective.6

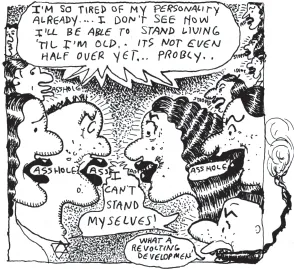

In addition to her quavering line, her work is characterized by deliberate visual inconsistency within its narratives. For instance, she frequently draws herself differently from panel to panel, even within the space of one story: she may draw with varying degrees of realistic linework from panel to panel; Aline’s clothes might suddenly change; bodies tend to swell and shrink (see figure 1.1). Kominsky-Crumb’s noncontinuous self-representation (like Lynda Barry’s accretive collages, as I will discuss in chapter 3) unsettles selfsame subjectivity, presenting an unfixed, nonunitary, resolutely shifting female self. Kominsky-Crumb makes her approach most legible in one striking panel from her graphic narrative autobiography Love That Bunch, in which she draws multiple selves who all declare, sharing a speech balloon, “I can’t stand myselves” (63; figure 1.2). The panel presents as impossible the choice of who among the many pictured selves is the “real” self; they all are.

Kominsky-Crumb’s texts return again and again to a set of motifs concerning sexuality and subjectivity, and they are layered and visually mixed, invoking in their crowded, irregular look the process of memory and the process of writing autobiography itself.7 Robert Crumb, addressing her in the introduction to Dirty Laundry, asserts: “Fine rendering doth not a great artist make. . . . Fine rendering can be a trap, a web of clichés and techniques. Your work is entirely free of such comic-book visual banalities. . . . You remain amazingly impervious to the pernicious influence of all cartoon stylistic tricks . . . which is mainly why so many devotees of the comics medium are put off by your stuff” (4). Further, even and especially with feminists, Kominsky-Crumb is a divisive figure. She explains, “right from the beginning I got a lot of flak from everyone for being so primitive and self-deprecating. [The feminist underground cartoonist collectives] were influenced by traditional comics. They had images of women being glamorous and heroic. I didn’t have that background” (“Kominsky-Crumb Interview” 58).

GOLDIE, SEXUALITY, AND EXPLICIT AUTOBIOGRAPHY: EXPANDING THE UNDERGROUND

Despite the fact that she is a progenitor of contemporary autobiographical comics, now a flourishing and even viably mainstream form, Kominsky-Crumb has always been rooted in the underground and independent comic book publication. With its laid-bare messy bodies and exuberantly messy lines, her work is perhaps the least commercial of the five authors I discuss here in its particular match of content and style. The arc of her career reveals a cartoonist developing a voice (both visual and textual) from the margins, deeply devoted to underground comics and the unconstrained mode of expression they make possible. While she has published three books—and her next, a collaborative work with Robert Crumb, will be published by W. W. Norton—she has also been profoundly involved, from the very beginning of her career, in comic book serialization.8 She published her work in underground titles such as Wimmen’s Comix, Manhunt, Lemme Outa Here!, Dope Comix, and Arcade, among others; edited the acclaimed Weirdo for five years; and founded the comic books Dirty Laundry, Twisted Sisters, Power Pak, and Self-Loathing Comics.9 Asked in a recent interview what she strives for in her art, Kominsky-Crumb replied, “I’m trying to create something that is influenced as little as possible by all the commercial forces out there that want to tell me what to buy and what to do” (“Unlocking” 341).

1.1 Aline Kominsky-Crumb (with Robert Crumb), two consecutive panels from Dirty Laundry Comics no. 1, 1974. Used by permission of Aline Kominsky-Crumb.

This positioning against mainstream commercial culture stems in part from Kominsky-Crumb’s upbringing in a social-cultural enclave she detested. Born Aline Ricky Goldsmith in Long Beach, Long Island, in 1948, Kominsky-Crumb grew up in Woodmere, in the Five Towns neighborhood. She writes in an author’s note that she spent her first seventeen years “in an upper middle class ghetto, surrounded by ostentatious materialism and rabid upward striving. . . . To say that I never fit into this world of ‘post war jerks’ is an understatement . . . but such intense alienation has provided me with years of comic-tragic material” (Noomin, Twisted Sisters: A Collection 139). She calls life at home with her parents, who were prone to violent fighting, “scary and unpredictable” (Need More Love 45). Kominsky-Crumb briefly attended SUNY New Paltz, left school pregnant at eighteen, ran away to join the hippie community of the Lower East Side (where she admits she “had wild sex and took lots of drugs right up until the minute I was ready to give birth”), gave her healthy baby up to a Jewish adoption agency, attended Cooper Union for one semester, and married Carl Kominsky in 1968 shortly after her father died of cancer at age forty-three (Need More Love 103). The couple moved to Tucson, where Kominsky-Crumb earned a BFA in painting, in 1971, from the University of Arizona. After she graduated, her friend and neighbor Ken Weaver (from the legendary New York band The Fugs), introduced Kominsky-Crumb to two underground cartoonists from San Francisco, Spain Rodriguez and Kim Deitch, who in turn introduced her to the newest crop of underground comics, including work by Robert Crumb and Justin Green. At age twenty-two, Kominsky-Crumb, whose marriage was shortlived, moved to San Francisco intent on drawing comics: inspired by Green’s “masterpiece of autobiographical revelation,” Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, she had already written and drawn her first story, “Goldie: A Neurotic Woman” (Need More Love 126). She glosses her first comics narrative as “about leaving my first husband, getting my Volkswagen, driving away and being free” (“Aline” 164).

1.2 Aline Kominsky-Crumb, panel from “Up in the Air,” Love That Bunch, p. 63. Used by permission of Aline Kominsky-Crumb.

By the early 1970s, as noted in the introduction, women in underground comics were producing the kind of work that they could not find in the mainstream or in the often sexist underground press. Yet Kominsky-Crumb’s first strip in print, “Goldie”—at which the male publisher of the collectively women-edited Wimmen’s Comix balked—was clearly innovative.10 “Goldie” shows Aline masturbating with different kinds of vegetables—the kind of explicit image that simply did not exist previously in the context of autobiography, whether “aboveground” or in the comix underground (figure 1.3). This kind of courageous work, even though she has her critics, made Kominsky-Crumb the “godmother” or at least the central pioneer of women’s comics autobiography, and it expanded the range and focus of the underground, without which we would not have, today, a contemporary literary comics culture.

The five-page story opens the 1972 inaugural issue of Wimmen’s Comix; it commences with a title panel that spotlights Goldie, looking serious, facing away from the direction of reading at a three-quarters angle in front of a black background. “In the beginning I felt loved,” the upper-case text begins. To the left of a small Goldie, wearing a teeny Star of David necklace, clutching a doll, and set off by appearing within her own black-background frame within the larger, lighter frame, is an elderly couple, presumably grandparents; the woman declares, simply, “The Princess,” while a younger couple, presumably parents, share a thought balloon to her right that self-servingly expresses their pride: “We made her.” The ensuing panels show Goldie excelling in school; mobbed by friends; playing outside: “Life was good,” reads a punctuationless floating text box. And then in the last panel of the page Goldie grows up a little: “With puberty came uglyness [sic] and guilt . . . . .” declares a box in the corner of a large panel in which a disproportionate, spotted girl stands facing readers (ellipses in original). The image is an inverse of the title panel: she is spotlighted in a harsh white; her arms are tiny stumps folded into a massive lower body. The creative spelling and inattention to normative rules of punctuation in this first strip establishes Kominsky-Crumb’s mode, in which language frequently is not “correct” and sentences are more expressive than grammatical.11 “Goldie,” too, demonstrates how language in Kominsky-Crumb’s work often sets up a staccato rhythm for the story that contrasts with the visual plenitude of the comics page.

The second page recalls an incident that Kominsky-Crumb returns to often in her work: her father announcing, about her looks, “Ya can’t shine shit!” Goldie’s miserable circumstances include listening to her parents have sex—“How can they do it? They’re both so disgusting” she muses, her ear up against the wall—followed, disturbingly, by her sexualization by her father: he marches towards her, arms outstretched (“Cum ’e...