![]()

1

TEACHERS AND LEARNERS IN SOCIAL WORK:

A FRAMEWORK

JUST AS SOCIAL WORK EDUCATION has been growing in recent years, so has our knowledge about teaching effectively. In 2007, the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) counted more than 180 accredited master’s programs and more than 450 accredited baccalaureate programs in the United States, with more being developed (CSWE 2007b). Total student enrollment in these programs was estimated at about 32,000 in baccalaureate programs and 39,000 in master’s programs in 2006/2007, all the students learning in either the classroom and/or the field. The Council on Social Work Education estimated that there were more than 8,000 faculty members in social work schools and departments in 2006/2007, 74 percent of them full time. These teachers and these learners are part of a profession that is predicted to grow in the coming years, in an increasingly multicultural society. These teachers and learners share the conviction that their clients need and deserve the services of social workers who are well prepared for this varied, complex, and demanding work.

In higher education generally, knowledge about how to teach effectively is expanding rapidly and is growing in sophistication. Social work educators traditionally have used a range of teaching methods. But even though many doctoral graduates in social work become full-time faculty in social work, only about one-third (Valentine et al. 1998) to one-half (Hesselbrock 2006) of social work doctoral programs require or make available courses on teaching. Because many doctoral students in social work decide to obtain a doctorate in order to enter academia, many would like better or more systematic preparation for teaching.

This book links the “practice wisdom” of today’s social work educators with current theories and knowledge about students’ learning and effective teaching methods. It is designed for newcomers to teaching in social work, for those who want to refresh their approach to their work, and for those in social work doctoral programs and educational administration to enhance their students’ education.

This book, which grew out of teaching aspiring social work educators, summarizes the existing literature on teaching and learning in social work. It also draws selectively on the literature in the field of higher education more generally to show how teaching can be applied to social work education specifically. However, the literature on teaching in higher education is typically addressed to teaching in the academic disciplines, and not to the professions. Thus, we must consider how this knowledge can best be applied to social work education, whose goal of nurturing student growth must be combined with ensuring that graduates will be effective and ethical service providers. In some ways, I have tried to write the book I wished I had when I began to teach the teachers.

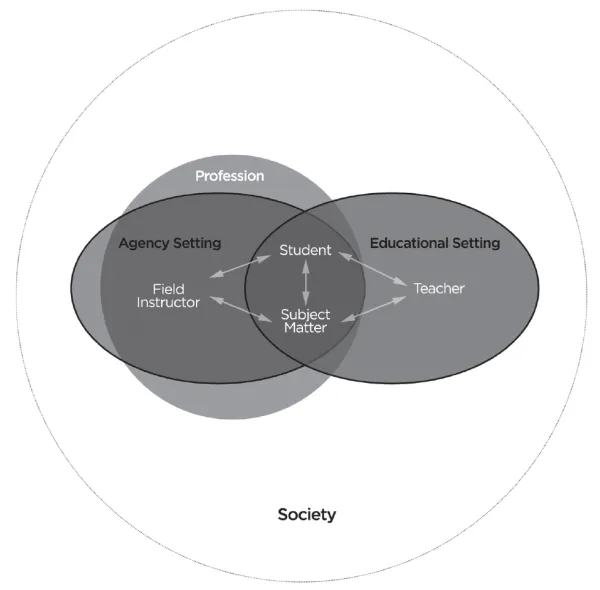

The framework I am using could be characterized as a “person-in-environment” perspective. Davis (1993), for example, described those factors that affect teaching and learning: the teacher, the learner, the subject matter, and the setting, meaning the educational institution, that is, the department or school and the university or college. Social work education has two settings for education: the classroom that is part of an educational institution and the social service agency in which field learning takes place. For a profession like social work, we also must consider the general social context, that is, the society in which the educational process takes place and in which the students will practice and apply what they have learned. A schematic representing this constellation might look something like figure 1.1.

The arrows at the center of the figure represent the processes of teaching and learning that place the teacher, the learner, and what is to be learned in a specific context. This book emphasizes the teacher, the learner, the settings in which they interact, and especially the processes and kinds of interactions they are engaged in. Among the several excellent recent books on field instruction and field learning in social work, now considered the “signature pedagogy” of the field (CSWE 2008), are those by Bogo and Vayda (1998) and Ortiz Hendricks, Finch, and Franks (2005). With the exception of a chapter on field learning by guest author K. Jean Peterson, the book concentrates on classroom teaching.

In the past, the literature in social work education predominantly addressed the subject matter of social work education, which is what the U.S. curricular standards focused on and what both beginning and experienced teachers tend to think about most. This is not surprising, since content is important, and determining what a social worker should know and be able to do is especially important to a relatively new field or profession. In addition, people are generally recruited to teach social work because of what they already know and know how to do. Because social work curricula differ and because curriculum content is addressed elsewhere, this book concentrates on teaching and learning and the contributions to them of teacher, learner, subject matter, and setting. My aim is to draw attention to aspects of teaching that may not be considered when preparing to teach.

FIGURE 1.1 Model of teaching and learning in social work context.

Bertha Reynolds (1942/1985) began her classic book on learning and teaching in social work by defining the subject of social work. Although I will not attempt to do the same, I agree with her that much content is generic to all social work. Reynolds, however, wrote only about graduate (and in-service) education, whereas this book intends to address teaching and learning in both BSW and MSW programs. Although the continuing education of professional social workers is thriving, continuing education and doctoral teaching each are sufficiently different from teaching in professional degree-granting programs to deserve separate treatment elsewhere.

Writing in the middle of World War II, Reynolds was acutely aware of how much social change and social challenges affect professional practice and social work education. Thus, while the influence of contemporary society—its problems and needs, ideas and ideologies, and resource issues—is never far from higher education in general, it is especially felt in social work education. Much of our discourse about curriculum is addressed to ensuring that what we teach is relevant to the changing world in which graduates will practice. This connection now includes bringing a global perspective to our work (CSWE 2008), which is a new emphasis in social work education in the United States.

The social work profession itself—its purpose, mission, and ethics—is intrinsically related to social aspirations and social needs, whatever the specific form of social work practice being taught. The subjects of social work programs must include the knowledge, values, and skills that define the scope and tradition of social work. Those who teach must be able to socialize students into the profession, and social work students must demonstrate that they can function as professionals with the requisite knowledge, values, and skills. Thus teachers, students, and learning environments must respond to professional norms in addition to the usual academic ones, which can lead to some predictable tensions.

Education in the professions means doing as well as knowing. There is a long tradition in social work of educating in the field as well as in the classroom. Social work education takes place in a variety of settings over which we, as teachers, have differing degrees of influence. While the traditional academy is in the process of discovering the value of real-world, doing-related, and community-based service learning, social work education has always made practicum learning intrinsic to its operations. Social work educators and social work students must contend with at least three kinds of settings: the college or university as a whole, the school or department and its classrooms, and the field agency. Tensions between school and university and between school and agency can affect students, teachers (their careers and their roles), and the curriculum.

Social work education takes place both inside and outside the academy, in world of the social agency. Field learning settings are part of the larger health and social service delivery systems to which human needs and current social problems are presented every day. Even though learning in the agency is not the main focus of this book, social work students are challenged to function in and transfer learning between both settings, meaning that classroom teachers must make what they do relevant to their practice. In addition, educators and academic administrators in social work must deal with two different teaching and learning contexts, and they have much more control over one of them than the other.

In part because we educate our students in both the classroom and the field setting, we use a variety of teaching modalities. Because we have defined social work education as including knowledge, values, and skills, we need different modes of teaching and learning to address them. Faculty must teach effectively, and students must learn effectively in both the classroom and the field, in classes and groups, and in dyadic supervisory and advisory relationships. We may require that students demonstrate their learning behaviorally, through examination, and/or through scholarly work. Much in the general literature on teaching and learning in higher education can help us choose among and improve on our teaching in all these modalities. In addition, many departments and school of social work are considering how best to incorporate new technologies, especially those that support distance learning. In figure 1.1, the complex, bidirectional set of lines that join teacher, student, and subject represent the teaching modalities used and the factors that must be considered when using them.

The literature has sometimes addressed who our students are, their motivations, values, and skills (or lack of them). We may be interested in what their personal histories contribute to or detract from their capacities to become effective social workers or clinical social workers. In addition, most schools try to recruit and retain students who reflect the diversity of contemporary society in race, ethnicity, language, religion, (dis)ability, and the like. In both undergraduate and graduate social work education, we are familiar with teaching what the higher education community calls “nontraditional” students, that is, those who are older and have significant life and work experiences. In fact, in graduate education, we tend to prefer to teach nontraditional students. This, in turn, has led to discussion of how adult education theory and models—androgogy instead of pedagogy—can be used to enhance teaching and learning in social work. We also have tried to identify students’ differing learning styles and professional developmental issues (see, e.g., Saari 1989). Finally, our current accreditation standards (EPAS), like most others, are challenging schools to examine our students’ educational outcomes more rigorously than in the past.

We know something (but not a lot) about the teachers who are currently working in social work education. We debate the importance and role of their post-MSW practice experience when hiring them and when admitting them to and preparing them in doctoral social work programs. We also know that as in other parts of the academy, women, minority faculty members, and teachers who concentrate on scholarly work, traditionally underrepresented groups may not fare as well in work assignments, teaching loads, publication, promotion, and other indicators of success in the academic workplace (LeDoux 1996). Even though the situation in social work is better than that in many other fields and disciplines, it is not yet a level playing field, despite our ideological commitment to make it so. Finally, we can do more to develop our faculty as teachers and as scholars and to help them succeed in their academic careers.

CONTENTS OF THIS BOOK

In each aspect of preparing to teach, many factors must be considered: teacher, learner, subject matter, setting, the profession, and society. This book looks at the aspirations, controversies, and tensions pertaining to diversity issues, which affect all aspects of the teaching and learning enterprise. Each chapter of the book highlights a different facet of being a social work educator.

Whatever the context, learning in the end is a personal enterprise, and any significant educational experience is always, to some extent, transformative for the learner. Chapter 2 compares some of the major theories of adult psychosocial and cognitive development that are commonly used in thinking about how students in higher education learn. These theories emphasize that social work education is adult education and that our teaching should be aimed at helping students think about more complex ideas. Learning styles also are important to what they say about effective teaching styles. In fact, enabling students to use a wider range of ways of knowing and styles of learning is itself an important educational outcome.

Chapter 3 considers the range of teaching modalities that can be used in social work education. Social work education, like other forms of professional education, requires knowledge, values, and skills. Teaching social work includes not only classroom instruction but also field instruction and advising. In addition, I describe the advantages and disadvantages of classroom teaching techniques, such as lecturing, discussion leading, using group and individual projects, and coaching and mentoring, with an emphasis on the teacher’s ability to expand his or her repertoire of teaching techniques and to match the teaching modality to content and to students’ learning goals and styles.

One way in which social work education has responded to the changing social context has been to address diversity issues, the topic of chapter 4. We speak about how the increasing diversity in U.S. society influences (or should influence) what we teach, that is, the curriculum. But our changing ways of understanding and dealing with diversity also influence who are students are, who our teachers are, and how the settings in which we teach—both the university and the social agency—respond to multicultural and other diversity issues. The tensions arising from these interactions are often points of anxiety or crisis but also opportunities for growth for students, faculty, and institutions. The ethics of the social work profession have helped sustain our collective and individual commitments to addressing diversity issues even when social forces tend to diminish them or render them invisible. Chapter 4 addresses the many challenges that remain in order to include diversity in what we teach, who we teach, and who teaches. We also review racial identity theory, especially in regard to teaching and learning and to understanding and overcoming some of the tensions in teaching about diversity in the current social context.

Chapter 5, by guest author K. Jean Peterson, covers teaching and learning in the field setting. Field learning must take into account the complexities of teaching and learning across the organizational boundaries of both schools and agencies. Peterson reviews the various models that social work education has used to frame this part of students’ education, common issues in student learning in the field, and the roles of the field instructor and the faculty–field liaison in supporting student learning. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the current pressures on field education and some ideas about what will be needed in future.

Chapter 6, by guest author James Drisko, discusses the use of electronic technologies in teaching and learning. From the complexities of distance learning to computer-aided classroom instruction, electronic technologies are a hot topic in the academy today. While some people may see these tools as a welcome revolution, others worry about the possible negative effects on the teaching/learning relationship. This chapter gives an overview of the common technologies being used in social work education today in various areas, along with an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of each. It includes tips on how and when they may best be applied from the perspective of someone who has considered them in relation to both teaching and practice.

These six chapters cover the key actors, settings, tools, and techniques in social work education. The next three examine other topics essential to understanding teaching in higher education. Chapter 7 looks at assessment and evaluation in social work education. One of the most worrisome tasks facing a beginning teacher is evaluating students’ learning. In addition, the gatekeeping function of social work education typically competes with the helping impulse that faculty feel toward students, rooted in their identity as practitioners. Although this chapter follows those on learning, teaching modes, field education, and technology, its premise is that in planning a course or curriculum, student assessments provide important opportunities for learning beyond what happens each day in the classroom. The more that learning outcomes are emphasized in higher education, the more important it is that student assignments not depend solely on tradition and prior practice but also on opportunities for students to demonstrate that they have achieved specific learning goals. How faculty are evaluated in their teaching by students and others also is a great concern. While there has been much creative work in higher education generally on evaluation issues, little seems to have entered the mainstream of social work education, although that is beginning to change. This chapter considers evaluation techniques related to both teaching and learning and how they can be used to enhance social work education.

Because of the many and far-reaching missions of institutions of higher education in today’s society, demands on faculty time and standards of excellence in job performance are limitless (Kennedy 1997). Chapter 8 describes faculty work, including classroom preparation, student advising and mentoring, committee work and other departmental and...