![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Mutual Fund Industry Growth and Importance in Retirement Plans

Mutual Fund Growth

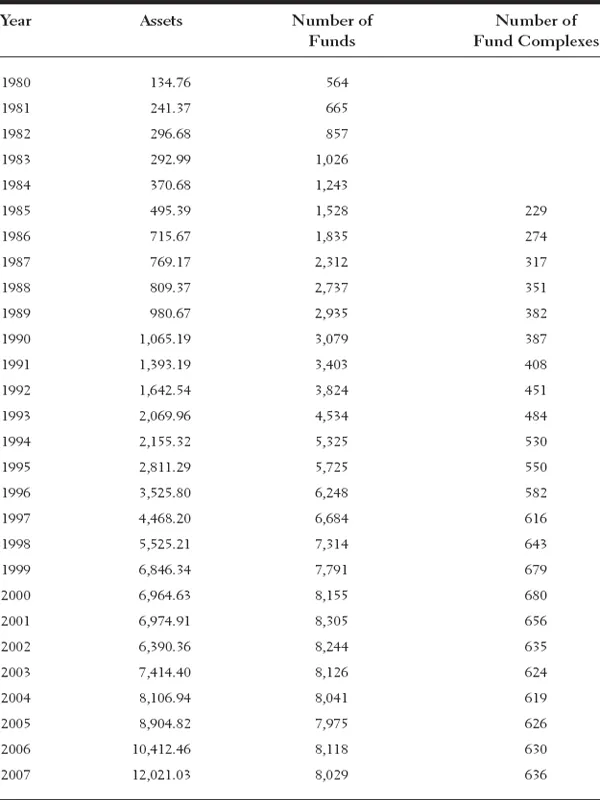

The mutual fund industry experienced slow, steady growth from approximately 1940 to 1980. Since then, the absolute amount of dollars invested in mutual funds has grown significantly. The number of households in the United States that owned mutual funds rose from approximately 4.5 million in 1980 to 50.4 million in 2007, or from 6 percent of total households in 1980 to approximately 44 percent in 2007.1 Net new money flow into mutual funds totaled $5.0 trillion from 1990 to 2007. As shown in Table 1.1, total net assets under management grew via asset appreciation and new money investment from $1.1 trillion in 1990 to approximately $12 trillion in 2007.2 The supply of mutual funds grew commensurately to meet this growth in demand, from 564 funds in 1980 to 8,029 in 2007.3 These 8,000-plus funds were provided by more than 500 fund complexes and investment advisers, compared with less than 200 investment advisory firms in the mid-1980s.4 By historic standards, growth in the number of funds and their asset value has been unprecedented since 1980, as the stock market offered the potential for relatively high returns during the 1980s and 1990s, and the aging baby boom population increased its savings for retirement.

Mutual Fund Growth in Retirement Plans

Mutual funds have become especially prominent in deferred tax retirement savings accounts, most directly in individual and employer-based individual retirement accounts (IRAs) and employer-based defined contribution plans, such as 401(k), 403(b), and 457 plans. Together, IRAs and defined contribution plans accounted for 52 percent of total retirement assets in 2007, compared with only 32 percent in 1985.5 Mutual funds managed 55 percent of defined contribution plan assets in 2007, compared with 8 percent in 1990, and 47 percent of IRA assets in 2007, compared with 22 percent in 1990.6

TABLE 1.1 Mutual Fund Assets, Number of Funds, and Fund Complexes, 1980–2007

Sources: Investment Company Institute, 2008 Investment Company Fact Book, p. 110. Strategic Insight, Simfund, Mutual Fund Database, 2008.

Note: Data excludes funds of funds. Numbers of fund complexes from Strategic Insight are available from 1985 onward.

The share of mutual funds in retirement accounts stems from a variety of factors, including government authorization of more attractive features for IRAs over time and the increasing conversion of defined benefit to self-directed defined contribution retirement plans. IRA investment expanded through new IRA plans that enhanced the incentive to invest, such as the Roth IRA, the employer-based saving incentive match plan for employees (SIMPLE IRA), the simplified employee pension (SEP IRA), and the salary reduction plan (SAP SEP IRA).7 In 2007, IRAs represented 26.7 percent of United States retirement assets.8

Mutual funds share of retirement plan investments has also expanded because private sector employers have been freezing, terminating, and switching from traditional defined benefit to defined contribution retirement plans in increasing numbers since the 1980s. Participants in defined contribution plans and IRAs seeking the least costly way to gain the benefits of professional money management and asset diversification have increasingly turned to both passively and actively managed mutual funds.

The Shift from Defined Benefit to Defined Contribution Retirement Plans

The shift from traditional defined benefit to defined contribution retirement plans gained increasing momentum in the 1980s. Various hypotheses have been offered to explain this shift. Some claim the decline in U.S. manufacturing and mining jobs, where private sector defined benefit plans were most prevalent, and the accompanying decline in the power of labor unions explain the reduced use of defined benefit plans. Others point to increased competition from globalization and more pressure on U.S. companies to remain cost competitive. Still others claim that employees prefer defined contribution plans because of matching contributions from employers and the ability to direct their own savings and investments for retirement. Whatever the explanations offered, defined benefit plans, which are lifetime annuities to retiring workers, are more costly for employers than defined contribution plans, because with the benefit plans, employers must assume the risk of increases in life expectancy that come with advances in medical science as well as the risks of changes in interest rates and stock market portfolio values over time. As an example, the sharp decline in interest rates and stock market returns in 2000–2001 greatly increased the funding requirements of defined benefit retirement plans to meet future plan liabilities. Lower annual returns and interest rates reduced compounding effects on total plan assets, requiring larger future assets.

As employers abandoned defined benefit plans, they generally substituted cash balance and defined contribution retirement plans, sometimes offering both plans in place of a defined benefit plan. Like defined benefit plans, cash balance plans also provide a lifetime annuity but tend to reduce the retirement liability for employers, because such plans are generally based on an account balance developed from monthly contributions and some earned interest rate. However, this tends to reduce benefits for older workers compared to defined benefit plans. Defined contribution plans free employers from lifetime payments to retirees. They also shift the risks of stock and bond market changes and the retiree's longevity from the employer to the employee. Employers often increase their matching amounts in defined contribution plans when converting from defined benefit plans to compensate older workers, at least in part, for the lower benefits they will receive under a defined contribution plan relative to the replaced defined benefit plan.

Growth in IRA and Defined Contribution Retirement Plans

According to data compiled by the U.S. Department of Labor, defined benefit plan assets in 2005 accounted for 21 percent of private sector employer-sponsored plan assets, down from 32 percent in 1992–1993, while defined contribution plan assets rose over the same period from 35 to 42 percent of private sector retirement plan assets.9

The shift away from defined benefit plans has naturally resulted in IRAs and defined contribution plan assets growing at a much faster rate than assets in defined benefit plans.10 Defined contribution plan assets exceeded private defined benefit plan assets for the first time in the early 1990s, and IRA assets exceeded defined benefit plan assets for the first time in 1998. At the end of 2006, defined benefit plans had grown to $2.3 trillion, but defined contribution plan assets and IRA assets totaled $4.1 and $4.2 trillion, respectively.11 Together, self-directed plans were almost four times as large as defined benefit plans in 2006. As private sector defined benefit plans continue to be phased out in favor of defined contribution and cash balance accounts, mutual funds will continue to grow as a primary investment vehicle for defined contribution and IRA accounts.

Underlying the growth in mutual fund and retirement assets over the last two decades were favorable stock market conditions. The 15 percent or so market interest rates of the late 1970s combined with rate regulation on savings accounts in banks and savings and loan institutions led to substantial growth in the number and assets of money market funds. Money market assets jumped from $3.9 billion in 1977 to approximately $220 billion in 1982, and the number of money market funds during this period increased from 50 to 318.12 This provided a first-time experience with mutual funds for many investors and, when the experience proved favorable, led to further investing in mutual funds. Recovery from the 1980–1981 and 1990–1991 recessions resulted in strong stock market appreciation and further investment in mutual funds. Demographic conditions were also highly favorable to mutual fund investing. When baby boomers began reaching middle age and increased planning for retirement, the demand for mutual funds grew through much of the 1990s.

Mutual Funds and the Pension Protection Act of 2006

The Pension Protection Act (PPA) of 2006 (Public Law 109-208), provides additional impetus for retirement investing via mutual funds. The PPA of 2006 includes somewhat inconsistent incentives for employers to continue or open new traditional defined benefit plans, but it provides unambiguous incentives for individuals to invest in IRAs and defined contribution plans. For defined benefit plans, the PPA of 2006 increases tax deductions for employers’ contributions, encouraging employers to maintain their defined benefit plans. However, the Act requires that employers eliminate all underfunding in defined benefit plans by a specific date, which provides an incentive for employers with financially troubled, underfunded plans to convert to plans with less demanding future liabilities, such as cash balance and defined contribution plans. The PPA of 2006 also facilitates employers switching away from defined benefit plans. Conversions from defined benefit plans had faced legal uncertainty prior to 2006 because of numerous lawsuits against employers, charging them with age discrimination against older workers.13 The lawsuits likely slowed the shift from defined benefit plans. The PPA of 2006 Act, however, protects employers from age discrimination lawsuits when switching to defined contribution plans, thus reducing the costs of switching.

The Act provided increased incentives for investing in IRAs and defined contribution plans. It raised the maximum amount of IRA contributions to $4,000 in 2006 and $5,000 in 2008, and provided for inflation, adjusting maximum contribution limits thereafter, encouraging larger investment in IRAs. Similarly, the Act raised dollar limits to $44,000 for defined contribution plans and $10,000 for SIMPLE IRA plans in 2006. In addition, catch-up investing by older workers for IRAs, SIMPLE IRAs, and 401(k) plans authorized in 2001 but previously scheduled to end after December 31, 2010, were made permanent in the PPA Act of 2006. The Act also eased the burden on employees in completing rollovers into IRAs, and encouraged greater participation in defined contribution plans by automatically enrolling new employees in 401(k) plans, unless they specifically opt out. Over all, the PPA of 2006 provides greater incentives for investing in defined contribution and IRA plans, which has further contributed to the growing demand for mutual funds.

Government Pension Plans: Further Opportunity for Growth in Mutual Funds

Historically, defined benefit plans have dominated pension plans for public employees. In contrast to private sector retirement plans, the government's power to tax provided assurance to many that such plans would not be chronically underfunded. However, this has not always been the case. Government budget restraints, public employees’ union demands, and voter hostility to higher taxes led some local and state governments to continue offering generous defined benefit plans while simultaneously underfunding employee pensions in favor of more immediate public expenditure priorities. A notable example was the city of San Diego, which expanded its unfunded pension liability from $96.3 million in 1995 to $1.4 billion in 2005 by increasing pension benefits but not providing for future funding. This ruined the city's credit rating and jeopardized its ability to issue bonds.14

Although San Diego may be an extreme example, local and state government pension plans are generally underfunded. A 2008 study by Wilshire Consulting on state-sponsored defined benefit plans found that for 56 state retirement systems reporting actuarial data in 2007, 75 percent were underfunded, with an average ratio of assets to liabilities of 82 percent.15 This is an improvement f...