![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

Comparative Perspectives on Democratic Legitimacy in East Asia

Yun-han Chu, Larry Diamond, Andrew J. Nathan, and Doh Chull Shin

EAST ASIAN THIRD-WAVE DEMOCRACIES are in distress. From Bangkok to Manila, Taipei, Ulaanbaatar, and Seoul, democratically elected governments have been embroiled in political turmoil. Most East Asian third-wave democracies have suffered inconclusive or disputed electoral outcomes, incessant political strife and partisan gridlock, and recurring political scandals. Frustrated citizens in Manila and Taipei more than once lost confidence in the efficacy of democratic procedures to the point where they tried to bring down incumbent leaders through the extraconstitutional means of “people’s power.” In Thailand in 2006, a crippling political crisis triggered a military coup.

Democracies in Asia are in trouble because they suffer from fragile foundations of legitimation. Nostalgia for the authoritarian past shadows these new democracies, many of which succeeded seemingly effective progrowth soft-authoritarian regimes. In Thailand, the Philippines, and Taiwan, a significant number of citizens harbor professed reservations about democracy and lingering attachments to authoritarianism. In the eyes of many citizens, the young democracies have yet to prove themselves. Even in Japan, the region’s oldest democracy, citizens show low enthusiasm for the political system. If Japanese democracy is secure, it owes more to a lack of support for less democratic alternatives—what we call authoritarian detachment—than to positive feelings about the performance of democracy itself. Such lukewarm support for its own system prevents Japan from promoting the soft power of democracy effectively in the region. Instead, paradoxically, it is the confident regime of authoritarian China whose public seems satisfied.

Many forces affect the emergence and stability of democracy. Among them are elite interactions, economic development, and the international environment. But popular attitudes are a crucial factor. Beliefs and perceptions about regime legitimacy have long been recognized as critical influences on regime change, with particular bearing on the maintenance or breakdown of democracy (Dahl 1971; Linz 1978). As early as the late 1950s, Lipset presented evidence demonstrating a strong positive relationship between economic development and democracy. He also showed that political beliefs, attitudes, and values were important intervening variables in this relationship (Lipset 1981). The path-breaking work of Almond and Verba and Inkeles and Smith showed that countries differ significantly in their patterns of politically relevant beliefs, values, and attitudes and that within nations these elements of political culture are shaped by life experiences, education, and social class (Almond and Verba 1963; Inkeles 1969; Inkeles and Smith 1974). In 1980, Inkeles and Diamond presented more direct evidence of the relationship between a country’s level of economic development and the prevalence among its people of such democratic cultural attributes as tolerance, trust, and efficacy (Inkeles and Diamond 1980). Subsequently, Inglehart showed that life satisfaction, interpersonal trust, and rejection of revolutionary change are highly correlated not only with economic development but also with stable democracy. He thus argued that “political culture may be a crucial link between economic development and democracy” (Inglehart 1988, 1990; Inglehart and Welzel 2005).

Theorists of the 1960s and early 1970s took political culture seriously as an autonomous factor shaping democracy’s evolution, while emphasizing the formative role of elite patterns and decisions in the early phases of system evolution or transition. Dankwart Rustow was the pioneer of his generation in advancing our understanding of the genesis of democratization and its stages. In his now classic model of democratic transition, Rustow identified four phases. His model begins with one prerequisite condition—national unity—founded on a widely shared allegiance to a given political community. Second, the democratization process is set off by a prolonged, inconclusive struggle over important socio-economic-political cleavages. What follows is a decision phase, which results in the institutionalization of some crucial aspect of democratic procedure. The last phase is habituation, during which elites and citizens both submit to the democratic rules of contestation (Rustow 1970). Progress in the habituation phase—subsumed under the concept of consolidation in most present-day democratization literature—is gauged by the strengthening of the normative commitment of elites and citizens to democratic procedures. Rustow’s seminal work, although not immediately influential among his contemporaries, paved the way for the second generation of theory on democratic transition that emerged a quarter century later.

Political and intellectual trends in the social sciences during the 1970s and 1980s challenged or dismissed political culture theory. Most political scientists writing at that time placed emphasis on social structure, elite transactions, and political institutions. For example, in his work on the authoritarian turn of Latin America, Guillermo O’Donnell (1973) pointed to the structural connection between the deepening of late industrialization and what he called bureaucratic authoritarianism, arguing that the experiences of many Latin American countries directly challenged earlier predictions that modernization would entail parallel processes of economic development and democratization. Other analysts of regime transition, such as Juan Linz and Alfred Stepan (1978), challenged the determinacy of these structural models and applied elite-actor models to analyze the uncertainty surrounding democratic breakdowns. Other scholars followed the lead of Samuel Huntington’s Political Order in Changing Societies (1968) to explore the role of political institutionalization in shaping dynamics in developing countries. This second generation of democratic-transition theory, led by the multivolume work of O’Donnell, Schmitter, and Whitehead and the writings of Adam Przeworski, stressed the analysis of choices and strategic interactions among contending elites within both the authoritarian regime and its democratic opposition (O’Donnell, Schmitter, and Whitehead 1986; Przeworski 1991).

Only in the 1990s with the surge of theoretical and empirical attention to the process of democratic consolidation—and the growth of mass belief in democratic legitimacy as the core element of this process—has political culture recovered a central place in the comparative study of democracy. Among recent scholars writing on democratic transition and consolidation, Linz and Stepan stand out for their appreciation of the importance of mass-level changes in political culture and their efforts to link the elite and mass levels of behavior and belief (Linz and Stepan 1996a; also see Gunther et al. 1995).

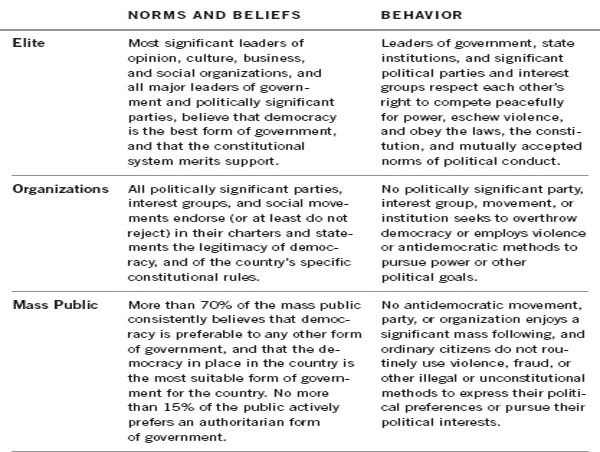

To be sure, public attitudes are not the sole determinant of the fragility or robustness of democratic regimes, but work in combination with other factors. One of us has suggested viewing the complex process of democratic consolidation in terms of six domains (Diamond 1999:68–69; also see Linz and Stepan 1996a:5–7). The argument is summarized in table 1.1.1 Consolidation takes place in two dimensions—normative and behavioral—and at three levels—political elites, organizations (such as parties, movements, and civic organizations), and the mass public. Although it is but one of six domains, the domain of mass norms and beliefs is crucial to consolidation. No democratic system can be secured that does not command long-term deep support at the mass level. Without such support, the regime is vulnerable to decay in the other five domains and then to collapse. It is in this sense that “the core process of consolidation is legitimation” (Diamond 1999:21).

Democracies therefore become consolidated only when both significant elites and an overwhelming proportion of ordinary citizens see democracy, in Linz and Stepan’s incisive phrase, as “the only game in town” (1996a:15). The consolidation of democracy requires “broad and deep legitimation, such that all significant political actors, at both the elite and mass levels, believe that the democratic regime is the most right and appropriate for their society, better than any other realistic alternative they can imagine” (Diamond 1999:65).

Thus the state of normative commitment to democracy among the public at large is crucial for evaluating how far the political system has traveled toward democratic consolidation (Chu, Diamond, and Shin 2001). Regardless of how international donors or academic think tanks rate the extent of democracy in a given country, this form of regime will consolidate only if the bulk of the public believe that democracy is the best form of government for their society, and that democracy of an acceptable quality is being supplied. The citizens are the final arbiters of democracy’s legitimacy.

In response to the third-wave transitions and associated developments in theorizing about democracy, a new generation of public opinion studies has arisen. Three large-scale regional survey projects came into being during the 1990s: the Latinobarómetro, launched by Marta Lagos; the Afrobarometer, co-led by Michael Bratton and Robert Mattes; and the New Europe Barometer (formerly the New Democracy Barometer), launched by Richard Rose.2 In the late 1990s, a global network of comparative surveys of attitudes and values toward politics, governance, democracy, and political reform began to take shape. Increasingly, the regional barometers have cooperated with one another to standardize questions and response formats in order to achieve global comparability.3

TABLE 1.1 INDICATORS OF DEMOCRATIC CONSOLIDATION

Source: Adapted from Larry Diamond, Developing Democracy: Toward Consolidation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), table 3.1, p.69.

Parallel to this emerging global network is the World Values Surveys (WVS), developed by Ronald Inglehart of the University of Michigan and other social scientists around the world, which assesses the sociocultural, moral, religious, and political values prevalent in many cultures. The WVS focuses on changing patterns of mass belief systems and examines their economic, political, and social consequences from the perspective of modernization theory (Inglehart and Welzel 2005). During the past decade, the WVS has extended its coverage to a number of emerging democracies in Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Asia.

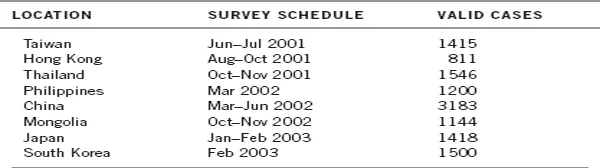

The East Asia Barometer (EAB), launched in 2000, was this region’s first collaborative initiative toward a network of democracy studies based on surveying ordinary citizens.4 The regional initiative was built on a substantial base of completed scholarly work in a number of East Asian localities (for examples, Chu and Hu 1996; Kuan and Lau 1988; Shin 1999; Shi 1997). Between June 2001 and February 2003, the EAB implemented its first-round comparative survey in eight political systems that have experienced different trajectories of regime evolution or transition: Japan, South Korea, Mongolia, Taiwan, the Philippines, Thailand, Hong Kong, and China.5 The EAB was the region’s first systematic and most careful comparative survey of attitudes and values toward politics, governance, democracy, reform, and citizens’ political actions. Table 1.2 and appendices 1 through 4 provide more details about the individual surveys.

In 2005 the East Asia Barometer began a second cycle of surveys. During the second wave, the project expanded to include Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia, and Singapore. In addition, the EAB formed a collaboration with a similar project coordinated by the New Delhi–based Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, which aims to assess the state of democracy in five South Asian countries: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal. The Asia-wide network of thirteen East Asian and five South Asian countries took the name Asian Barometer Survey of Democracy, Governance, and Development (ABS). The Asian Barometer Survey stands as the largest link in the global survey network for the study of democracy, covering eighteen political systems, more than 48% of the world’s population, and the bulk of the population living in the developing world.

TABLE 1.2 SURVEY SCHEDULES AND SAMPLE SIZES OF FIRST-WAVE EAB

Note: Ns (sample size) in some tables and figures vary because of the effects of weighting.

The first-wave eight-regime study reported in this volume permits a series of nested comparisons. The data from South Korea, Mongolia, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Thailand allow us to compare the popular legitimation of democracy across the region’s five new democracies. Data collected from Japan, Hong Kong, and China throw light on popular beliefs and attitudes in societies living under different kinds of regimes: the only long-established democracy in the region; a former British colony that has enjoyed the world’s highest degree of economic freedom but witnessed its momentum of democratic transition slow after retrocession to Chinese control in 1997; and a one-party authoritarian system wrestling with the political implications of rapid socioeconomic transformation while resisting a fundamental change of political regime. Thanks to the existence of comparable data from other regional barometer surveys, we are also able to compare patterns of mass attitudes toward democracy in our region with thos...