![]()

chapterone

Some Notes on “Notes on Camp”

TERRY CASTLE

These notes are for George Eliot.

Rereading my abstract for this essay (composed last year for a conference), I confess to feeling a bit bemused—particularly by the cool, bureaucratic, indeed “abstract” tone I chose to adopt for it:

Susan Sontag’s essay “Notes on Camp” (1964) remains—in the minds of many—her defining work. With good reason: it is an uncanny, bravura accomplishment and helped to set in motion a host of intellectual and cultural transformations that would come to fruition over the next four decades. For reasons worth exploring, Sontag herself came to dislike the essay and in later years took umbrage at anyone who mentioned it or wished to discuss it. I hope to examine both the uncanniness and the umbrage: why “Notes on Camp” remains unforgettable (one still knows sentences from it by “heart”) and why it evoked in Sontag such self-distancing and contempt.

What is held at bay in this careful little statement—and the holding at bay, I realize, is both precarious and more than a little Sontagian—is precisely any hint of the personal: any sense of the roiling, arm-flapping, flowing-scarved, silver-maned emotions that Sontag—the writer, the speaker, the monstre sacrée, the semi-or-briefly-or-not-quite-friend—automatically evokes in me. True, I mention a certain susceptible reader, an unnamed “one” who supposedly knows lines from “Notes on Camp” by heart—but even there, I see, I’ve put the word “heart” in campy (if vaguely incriminating) quotation marks. I’m particularly struck by the abstract’s oddly fraught vocabulary: the words “uncanny,” “dislike,” “umbrage,” “wish,” “hope,” “unforgettable,” “self-distancing,” and “contempt” might suggest something more histrionic than the usual panel-discussion fare. Still, the thing keeps the lid on well enough to qualify as “academic”—i.e., to deaden the reader with charmlessness and official-sounding phrases.

But dispassion be damned: I find I can’t talk about “Notes on Camp” without “getting personal” at once. Camp, after all, is itself bound up with the personal—with the freaks of individual taste, with unusual or flamboyant modes of self-presentation. Human beings can be camp, of course; what makes them camp, Sontag argues, are precisely certain exaggerated “personality mannerisms.” The film world offers many examples. Among Sontag’s icons: the haunting androgynous Garbo; the flamboyantly feminine Jayne Mansfield; the “great stylists of temperament and mannerism,” such as “Bette Davis, Barbara Stanwyck, Tallulah Bankhead, Edwige Feuillière.” (I’ll come back to this interesting little pantheon in a moment.) Though not an actress or performer in the ordinary sense, Sontag herself could no doubt be added to this list of “camp” lady-thespians. In person, she was as eccentric, theatrical, and mesmerizing as any of them.

But “Notes on Camp” is itself an insistently personal piece of writing—more backhanded confession, I would argue, than truly analytic accounting, more flight of self-expression than impersonal treatise. How do I know? The glib answer would be because it elicits a similarly autobiographical urge in me. However veiled, confessional impulses are always contagious, and as soon as the young author, thirty-one at time of the essay’s publication, begins to list what things are “camp” and what aren’t, I can’t help but feel she wants both to reveal herself—the books she has read, the films she’s seen, the personalities she has encountered, what she thinks is funny, what she thinks is sexy, what she thinks is dumb, who she is, in other words—and to seduce her imaginary reader into some corresponding self-revelation. I’m happy to oblige: rereading “Notes on Camp,” even now, all I want to do is to seduce back (however pathetically) by itemizing all the books I’ve read, films I’ve seen, what I think is sexy, dumb, beautiful, etc., etc. Part of the essay’s allure lies in its cataloguing mania, its strange urge to specify—an urge so intense and charged as to become a form of greeting and provocation, a complex hello to an absent yet much-desired unknown. The essay’s mock didacticism, I would offer, is only a screening device. Though it may lend the essay a superficial air of intellectual rigor and self-restraint, it also allows its author to gesture—as in a journal intime—toward a tumultuous world of feeling. This indirect yet potent insinuation of feeling—especially, I think, of feelings associated with sexuality—may explain in part why Sontag was so uncomfortable with the essay in later years. The cool, analytic, supposedly educative pose was simply a rhetorical gambit; the private content, in retrospect, too obvious, jejune, and exposed.

First, a field sighting: It’s 1995 and Sontag has been invited to the Stanford Humanities Center as a Distinguished Visitor. On the first evening after her arrival, the wealthy donors who have subsidized the visit, an elderly physicist and his wife, hold a small and select reception at their bucolic McMansion in Portola Valley. After we perambulate the Japanese garden—a terraced extravaganza with gazing balls, philosopher’s stones, and mock-Shinto shrines—and gather sedately for cocktails on the deck, one of the older male guests remarks, by way of gallant icebreaker, on the extraordinary influence of “Notes on Camp” and how much he still admires the essay. Nostrils flaring, Sontag instantly fixes him with a basilisk stare. How can he say such a dumb thing? She has no interest in discussing that essay and never will. He should never have brought it up. He is behind the times, intellectually dead. Hasn’t he ever read any of her other works? Doesn’t he keep up? As she slips down a dark tunnel of rage—one to become all-too familiar to us over the next two weeks—the rest of us watch, horrified and transfixed.

Now the offending interlocutor is a person of no little eminence himself—the inventor, in fact, of the birth-control pill. He is clearly not used to having women tell him to shut up and feel ashamed of himself. He sits down, somewhat groggily, on a sort of embroidered tuffet-thing and falls into chagrined silence. That the whole scene—the Japanese lanterns hanging in the eucalyptus trees, our pink-tinged cosmopolitans, the convenient tuffet, and Sontag’s operatic outburst—could also be described as camp of a fairly high order, seems lost on the party’s still-incensed guest of honor. For some time afterward, Sontag simply glowers—magnificently—rather like Maria Callas in the famous film clip from Tosca at the Paris Opera, just after she’s stabbed Tito Gobbi, the rotund singer playing evil Scarpia. Muori, muori!

Coming so soon after Sontag’s arrival, the episode was obviously God’s way of warning us: don’t ever mention “Notes on Camp” in front of her! Or if you must, be very, very careful. More by luck than design, sheer sycophancy saved me from similar humiliation: soon after we were introduced I made a quasi-joke about having first read “Notes on Camp” when I was nine. The remark delighted Sontag and to my mingled pride and embarrassment she repeated it later during a seminar on The Volcano Lover. (No ban from her on discussing the novels of course; she was ready to expatiate on them for hours.) My claim to precocity, I feel obliged to explain, was not entirely obsequious untruth. Certainly I have a vague prepubescent memory of rifling through a stash of magazines at my father’s house in the early 1960s and discovering an article that I now think might have been “Notes on Camp.” I just can’t be sure what magazine. It’s hard to believe it was Partisan Review, the periodical in which “Notes on Camp” first appeared in 1964. For some weird reason I keep thinking it was Vogue. But why would my decidedly un-campy father, a cold and morose space engineer, have been reading Vogue? Not that he would have been reading Partisan Review either. I’m forced to consider the possibility that I may have made this whole Sontagian “scene of reading” up. Still, the thought of having been so “downtown” at an early age—a sort a juvenile Des Esseintes—is too gratifying, I confess, for me to disavow at this late stage.

Back to Sontag and the personal. Out of what kinds of private experience might a love of camp arise? When you reread Sontag’s essay it turns out that she is spectacularly vague about the emotional dimensions of camp—what psychic determinants may go to produce the camp “sensibility” in any given individual. Instead, she leaps immediately to the sociological and an explication that is sketchy at best. The appreciation of camp, she says, is usually found in “small urban cliques,” where it functions like a “private code, a badge of identity even.” An ironically cultivated affection for camp phenomena—the bloated films of Cecil B. De Mille, Liberace’s sequined outfits, the histrionic dancing of Martha Graham, male figure skaters—can be a way, she suggests, for the socially alienated to feel part of a coterie, a select group of mock cognoscenti. Like the Black Mass of old, camp facilitates Satanic small-group bonding: ordinary aesthetic values are inverted, the bad worshipped in place of the good. You and your fellow warlocks make a heaven out of hell, and the ugly, it turns out, is the new divine. Late in the essay, of course, she links this perverse rebel-angel sensibility with male homosexuality: gay men use camp, she argues, to create ironic solidarity in the face of social opprobrium. Camp taste, according to Sontag, is simply a late and paradoxical version of “aristocratic” taste—snobbish, witty, amoral, knowing. By treating the shoddy and overblown products of mass culture as “fabulous” or “heavenly,” Sontag avers, gay men transform themselves—with an irony at once comic, self-conscious, and voluptuous—into a new aesthetic vanguard or smart set, a fey cohort of (pseudoaristocratic) patron-connoisseurs.

Now all of this is no doubt true. But it also leaves a lot unsaid—or at least spectacularly undeveloped. Indeed, Sontag’s final, seemingly throwaway comments on the “aristocratic” nature of the camp sensibility, in particular, seem to obscure certain crucial underlying psychological questions. What impulses—conscious or unconscious—make someone fantasize about being an aristocrat? Blue-bloodedness is hardly something you can choose, and besides, in most Western democratic societies the aristocratic premise itself has long been officially discredited. Yet as Freud once famously suggested, the wish for such high station is a common one and in some individuals neurotic in the extreme. For Freud the wish is linked, of course, to what he called—in the famous 1908 essay of the same name—the “family romance”: the childhood fantasy that one is of royal birth and one’s humdrum, dreary, or fallible parents merely vulgar, low-status impostors. Through some mysterious accident—some dire mix-up in the cradle perhaps—one has ended up stuck with them, but it’s obvious (at least to the child) that everyone is living a lie. How could such a dull, talentless, badly dressed, and inconsequential pair have produced such a superior being as oneself? No doubt one’s real parents are a glamorous king and queen who will one day reappear, identify themselves as such, and take one back with them to that fairy-tale place one should have rightfully occupied since birth. One’s changeling status will be revealed; one’s exalted destiny, confirmed.

Freud explained the family romance as part of the process—always difficult, often excruciating—by which the young child seeks to liberate himself or herself from parental authority. This separation typically begins in wounding and disappointment: the child’s feeling—Freud writes—that he or she has been cruelly “slighted” by the parents. The birth of a sibling, classically, can elicit this narcissistic sense of injury: one feels displaced, neglected, abandoned. Injury in turn produces rage, and, at least in daydream, a wish to retaliate. On the unconscious level the assertion of royal birth is a striking act of symbolic vengeance: an indirect yet psychologically gratifying way of “doing away with”—or at least nullifying—one’s thoughtless, inept, selfish, and no doubt malevolent progenitors. In the most extreme cases it is the functional equivalent of patricide or matricide.

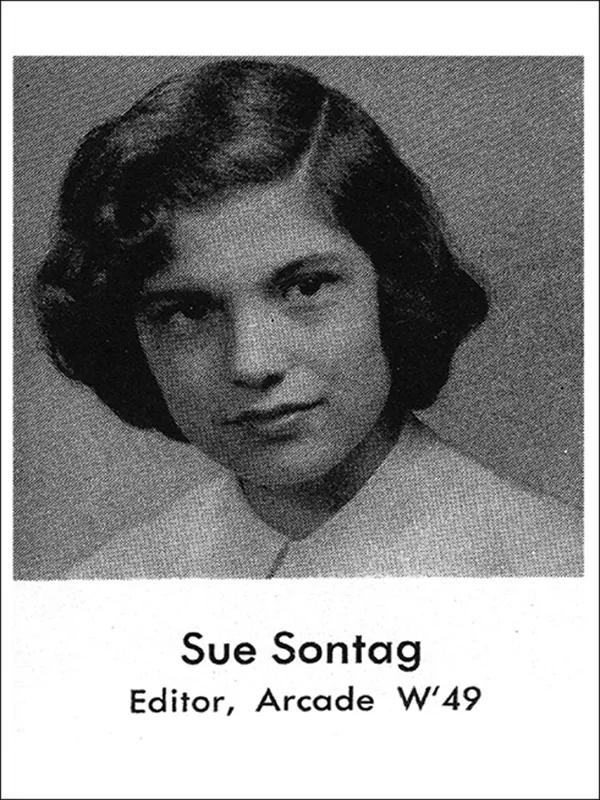

Now, if Sontag were alive and kicking today, I would hesitate, I’m sure, to offer the theory I’m about to float: a fear of defenestration would no doubt inhibit me. But I do think—have always thought—that “Notes on Camp” hints, fairly flagrantly, at something that might be called the Sontagian family romance. My theory is entirely speculative and subjective—some will say absurdly subjective. But at the essay’s emotional core I can’t help but infer authorial feelings of pain and anger—an undercurrent of indignation if not, indeed, a desire for revenge. Revenge on whom or what? I have no special knowledge about Sontag’s childhood—she seldom discussed it—but given the singular eminence she achieved, it’s very hard indeed not to be struck by the oddity and unexpectedness of her early years. Like Swift’s Gulliver, she’s always seemed a sort of lusus naturae—a biographical goof or non sequitur. How did she ever get from Point A to Point B? Born in New York, okay…—but raised in Tucson, Arizona, followed by Los Angeles? Father a fur trader in China (!) who died when Sontag was five? The mysterious navy-captain stepfather whose name she adopted in place of Rosenblatt? Three years at North Hollywood High? “Sue Sontag’s” yearbook picture is beyond discombobulating. (People usually giggle when they see it.) And where, in all of this, was Sontag’s mother? No doubt because I myself hail from San Diego, the Southern Californian connection particularly confounds me: I find it difficult to associate the stunted cultural ambiance of my own smog-enhanced childhood—a pageant of Taco Bells, Mobil gas stations, and Midas Muffler shops—with anyone as epicene as the author of Against Interpretation.

Sontag once wrote, very charmingly, in the New Yorker about an extraordinary high-school visit she and a geeky male friend paid to Thomas Mann, then living out his later years in exile in Los Angeles. What I remember most about the essay was Sontag’s account of Mann’s Old World courtliness and hospitality but also the sense she conveyed, obliquely yet ferociously, of the barrenness of her early life—the intellectual, aesthetic, and emotional impoverishment of her family situation and West Coast milieu, and her extraordinary yearning, even then, to be somewhere else, to helicopter herself up and out and into a world intellectually, artistically, and emotionally refined enough to satisfy her complex needs for beauty, love, seriousness, and permanence.

Figure 2 Susan Sontag’s high-school yearbook photo. Source: Courtesy of Kevin Killian.

The sensitivity to camp, I think, is intimately related to childhood disappointment—to the feeling of being misplaced, misunderstood, fine but unappreciated, “wasted” on those around one. As a child, you can’t help blaming the dullness of existence on your parents, it would seem: they are the ones, after all, who seem responsible for the unglamorous setting in which you find yourself. They seem to have arranged, if not created, the whole banal mise-en-scène. How easy for an intellectually precocious child to begin thinking of her parents as vulgar and stupid. Such resentment—often exfoliating wildly in adolescence—may cast back in turn to even earlier pains, losses, and “slightings,” the archaic, mostly suppressed traumas of infancy.

In this fraught psychic context the love of camp mediates, one might venture, between childhood outrage and a more sophisticated “adult” self. From one angle, camp objects summon up the detested paraphernalia of the past—they are emblems of that world of ugliness, dishonesty, and emotional bathos one prides oneself on having escaped or transcended. Camp is indeed heimlich—excruciatingly bound up with “home” in its negative aspect, the seemingly trashy, dreary, or love-starved parental milieu. Yet camp objects are also unheimlich—precisely because of the way, like mortifying phantoms, they can stand in for the parental.

The camp sensibility grows out of revulsion and disgust: you cringe at the thought of a fridge magnet in the shape of Michaelangelo’s David; you recoil, listening to Tristan, when the onstage Isolde—fat and freaky—reminds you of your morbidly obese stepsister who lives in Van Nuys. At the same time, however, your repugnance elicits guilt. Some transvaluation of the negative emotion is necessary: some psychological revision. Hence what Sontag, in one of her essay’s more saccharine asides, calls the affection, even “tenderness” with which camp objects or experiences are rehabilitated. (“Camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature. It relishes, rather than judges, the little triumphs and awkward intensities of ‘character.’” ) One purports to “adore” the very thing that at one time depressed, disgusted, mortified, frightened, etc., etc. “Fabulous” as she may be onscreen, who would really want Joan Crawford for his or her own “Mommie Dearest”? The appropriate real-world response to such a vile and selfish person—especially if she were in charge of looking after you—would be hatred or fear.

The homosexual theme in “Notes on Camp” is profoundly linked, I would argue, with the Sontagian “family romance” and helps, in turn, to explain the antipathy the essay evoked in its author later in life. Again, I intuit—but again, out of a kind of fellow feeling. Viewed in hindsight, the emphasis on homosexuality in “Notes on Camp” strikes me as spectacularly overdetermined—as part of a coy yet now-unmissable “coming out.” Not that many readers would have absorbed it as such in 1964: though Sontag seems regularly to have referred to her “homosexuality” in her diaries of the 1950s and early 1960s—some astonishing portions of which recently appeared in the New York Times magazine—she refused, as everyone knows, to speak publicly about her lesbian relationships until late in life. There is nothing in the wa...