![]()

1

Tatau and Malu

VITAL SIGNS IN CONTEMPORARY SAMOAN LITERATURE

In two works by contemporary Samoan writers, tattooing produces and proclaims the psychological and social place of the tattoo bearer. Albert Wendt’s short story “The Cross of Soot”1 depicts a young boy whose partially completed tattoo, begun by a condemned prisoner just before the man leaves to be executed, represents the way the boy “crossed from one world to another, from one age to the next.” The tattoo, as the boy’s mother recognizes, stands as a mark of that passage: “For the first time her son was no longer afraid to stare straight at her when she was angry with him. He had changed, grown up” (“Cross,” 20). In Sia Figiel’s novel They Who Do Not Grieve,2 a young woman is torn away from receiving a full-body female tattoo when it is only half completed. The character is prevented from receiving designs that help produce a full personal and social identity, and the uncompleted marks thus create a disgrace, leading her mother to disown her and ban her from their village.3

In both works, tattoo helps constitute Samoan subjects, and in both works the process is interrupted.4 The tattoo serves as a sign of the traditional subject, but, in these depictions, because it cannot be completed, it also serves as a sign of a new subject. The forestalled pattern makes visible a process inherent in even completed tattoo: these marks on skin signal the splitting or doubling of subjectivity, a mechanism by which the individual human subject is produced continually and repeatedly.

The continuing production of the subject corresponds to the continuing movement of the tattoo. Even traditional tattoos embody the cross-cultural traveling of signs, making visible and material the process by which culture moves both within and beyond the Pacific. That is, in Samoan stories (as in Tongan ones), the tattoo comes from Fiji; in Fijian stories, from Samoa; in Māori stories, from the underworld.5 Even in its Pacific homelands, where tattooing has been practiced for three thousand years, in places that developed their own distinctive designs and techniques,6 the tattoo is a sign of elsewhere. The patterns at once promise that the bearer will be at home—by bearing marks of belonging, meaning, and identity—and inaugurate a redoubled journey toward creating here from elsewhere. This apparently most fixed sign proclaims that the subject is as much an itinerary as an identity, that location is as much a passage as a place.

The Samoan word tatau helps create the English word tattoo.7 In part because of the way the word and practice have traveled, in English and around the world, Wendt’s and Figiel’s portrayals of tatau offer several important implications for models of reading, in fields including Pacific, postcolonial, and psychoanalytic studies. The portrayals and practices of tattooing insist on the materiality and the local production of sign and word, of image and text, even as they make explicit the ways tattoos travel, not least the exporting of the practice of tatau to the world as tattoo, its Pacific origins often obfuscated.

The process by which the Pacific and the rest of the world meet and shape one another has sparked debate in Pacific literature studies. Often scholars trace the interactions between the Pacific and the rest of the world by using paired opposites: literature and theory, for example, or insiders and outsiders.8 These formulations capture the oppositional impulses of much Pacific writing, which is often propelled by a powerful decolonizing impulse. On the other hand, writers and artists often achieve profoundly transformative work by creating a balance between and among these pairs and by challenging the very categories that create such polarities. Such an impulse is not surprising, since these classifications may limit political, artistic, and human expression.

To take a look at what these paired opposites might look like, Paul Sharrad, for instance, proposes that “the ‘inside’ of Pacific Literature, if it is broad and flexible enough, can appropriate a central position in literary debate not because it is essentially oppositional to a notional Western hegemony but because it can actually stand as a working model of much of the theory commonly labeled and used as Western.”9 Sharrad makes this statement in the context of proposing how important it is to work against treating Pacific literature as innocent of theory, a point that is very valid. But Pacific literature, more than standing as model of so-called Western theory, also challenges many of its terms and assumptions. In other words, Pacific literature does not exemplify so-called Western theory, but questions how such categories are produced.

Examining tattoo extends this discussion by focusing on material and textual production that reveals the constitutive relation of the inside and outside, literature and theory, the Pacific and the West. It is not necessarily that Pacific literature serves as a working model of Western theory—or even that the two concepts have a fixed, much less binary, relation, much as current versions of “the local” and “the global” help constitute one another. Nor does so-called Western theory validate and complete Pacific literature.

Instead, as Selina Tusitala Marsh suggests, theory is not foreign to the Pacific. In her essay “Theory ‘versus’ Pacific Islands Writing,” she begins with a poem and a defiant “refusal to see theory and art as incompatible entities, and second, to view theory solely as something foreign and outside myself.”10 The poem presents her own telling of Pacific stories as containing collective significance for herself and for Pacific Islands women. The poem begins with a lower-case “i” and closes with “we,” using oppositions to move toward unity for poetry and theory and for “tama‘ita‘i,” or Pacific Islands women.

By extension, the tattoo bears its own theories. The tattoo also offers an invitation to retextualize the well-rehearsed postcolonial text, to retheorize familiar psychoanalytic theories. As Epeli Hau‘ofa declares, contrary to the widely accepted view that the Pacific consists of isolated islands adrift in a vast sea or is outside the major world movements of capital and culture, “Oceania is vast, Oceania is expanding.”11 Oceania has already traveled into high French theory, including Jacques Lacan’s. Much as Wendt and Figiel portray the tattoo’s production of the doubled or split subject, in the lectures collected as Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-analysis,12 Lacan uses the tattoo to consider what he terms the split or barred subject and identifies the tattoo as part of a universal process: the creation of the subject. As this chapter investigates in detail, whereas Lacan presents the tattoo as a general, nonlocalized figure, Wendt’s and Figiel’s portrayals account for the tattoo’s material and corporeal effects, its origins in Oceania, and its function in inaugurating the specifically Samoan subject. The Samoan works treat the production and movement of the tattoo, reshaping the English language and narrative conventions to create a written version of tatau. They also make possible a critique of particular theories, such as Lacan’s, that have been viewed as universal, but that both contrast and coexist with Pacific considerations of tattoo and subjectivity. Restoring portrayals of Pacific tattoos to the conversation does more than reverse the typical vector of using European theory to read works from “other” literatures; it makes plain some of the ways the subject is produced in literature and theory.

MARKED HISTORIES

Tatau ushers the bearer into language. The patterns signal the bearer’s status as clothed for life: “Clothed not to cover your nakedness but to show you are ready for life, for adulthood and service to your community, that you have triumphed over physical pain and are now ready to face the demands of life, and ultimately to master the most demanding of activities—language/oratory.”13 The pain of tatau not only helps create the subject, but it also readies the subject for the intricate demands of speaking (oratory in Samoan, for instance, includes a formal or respect language that has as many as five registers, some reserved for specific persons of higher status). Tattooing is part of a process that is more than individual. Having a tattoo, Wendt declares, is a “way of life” (“Tatauing,” 19).

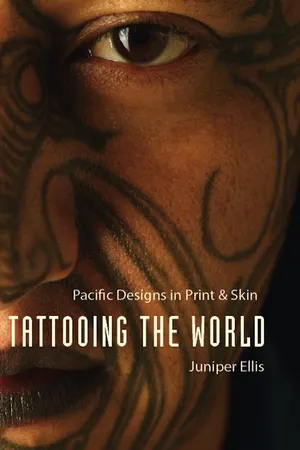

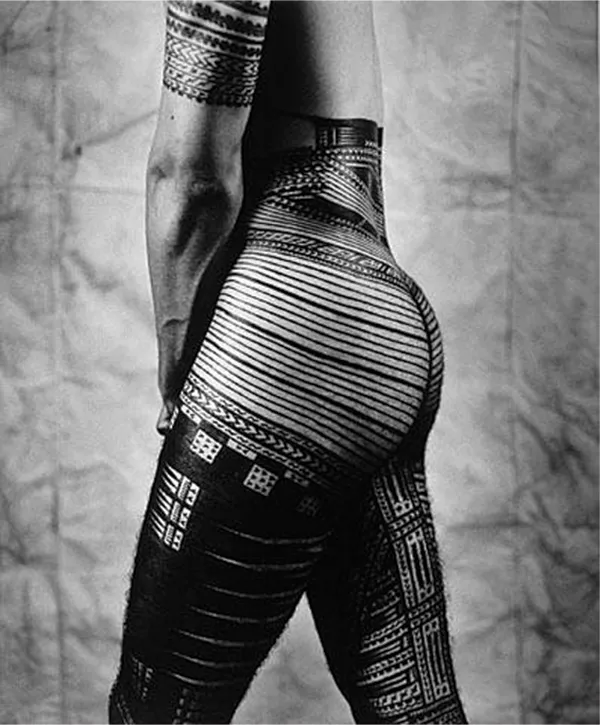

The word tatau in Samoan refers generally to the practice of marking the skin, and specifically to designs worn by men from their navel to their knees. These designs form a full-body male tattoo—termed colloquially the pe‘a. Figure 4, “Self-portrait with side of pe‘a,” by Greg Semu, presents an example of this type of tattoo. The malu, made with distinct motifs and patterns on a woman’s thighs, is the female counterpart. Figure 5, a still from the film Measina Samoa: Stories of the Malu by Lisa Taouma, depicts the malu pattern, named for the distinctive triangular motif that adorns the area just above the back of a woman’s knees. These stunning images at once present a living art and comment ironically on the tradition of representing such art in anthropological displays.

Historically, tattoos could be used to reinforce an existing order. In his study The Samoa Islands,14 written when colonial powers began consolidating their presence in Samoa, the early anthropologist Augustin Krämer notes that while a chief’s son could “choose his time” and be tattooed when he was almost full-grown (so that further growth would not “draw the pattern apart” [Samoa, 68]), other young men were obliged to accompany him, even if they were not full-grown. (Carl Marquardt verifies the practice in 1899, as does Margaret Mead in 1930.)15 Marquardt notes that young women, too, often received tattooing at the same time as the chief’s son.16 Thus, though not all young women took their tattoos at the same time, the creation of malu was similarly social and collective. Producing the designs could be one way of ensuring an orderly succession.

FIGURE 4. Photo by Greg Semu. “Self-portrait with side of pe‘a, Basque Road, Newton Gully,” 1995. Gelatin silver print, toned with gold and selenium. Published with permission of the artist and Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki.

On the other hand, tattoo can disrupt the existing order. In colonial times tatau represented an overt proclamation of allegiance to Pacific ways rather than to the language, culture, or political hierarchies brought by outsiders.17 The first Samoan independence movement—the 1908 Mau of Pule, which advocated autonomy from the German administration—like the 1920s Mau movement against the New Zealand administration, embraced tattooing as a marker of Samoan ways.18 Since the nation achieved political independence in 1962, Wendt notes, there has been a resurgence of tattooing (“Tatauing,” 23), one that corresponds to Samoan literature in which writers use tatau as a structuring principle.

FIGURE 5. Photo by Lisa Taouma. Still from Lisa Taouma, Measina Samoa: Stories of the Malu, 2005. Published with permission of the artist.

Tattoo can thus serve as both a transmission of and a challenge to differing forms of authority, in a double movement that encompasses the status of the designs; at once more than skin deep and marking the skin as a surface, the patterns remain both inside and outside the body.19 The figures by extension make visible subjectification, by which subjects claim and are claimed by the processes that reproduce culture. The figures show the simultaneous creation of individual and social standing places, as a person seeks the designs that express the interior and absorbs the patterns that mark the exterior: “The basic schema of tattooing is thus definable as the exteriorization of the interior which is simultaneously the interiorization of the exterior” (Wrapping, 39). As they explore this process, Wendt’s and Figiel’s accounts make possible a critique of Lacanian and finally of Samoan models of subjectivity. The tattoo’s interior and exterior fields both emphasize and challenge the Lacanian focus on a discrete, bounded subject and, in turn, the Samoan focus on a collective, corporate subject.

In her introduction to Written on the Body,20 Jane Caplan suggests that Western European tattooing may have been active in 1769, when Captain James Cook helped import tatau into English while his traveling companions incorporated Pacific designs into their skin. Responding to this point in his introduction to Tattoo, Nicholas Thomas notes the surprise that Cook and his fellows evinced at the practice, which indicates that any extant European tradition could not have been widely known. By extension, cross-cultural readings of Lacanian theories and Samoan literatures make visible the way Pacific tattoo moves into other parts of the world. From this transit emerges the sign that creates the subject.

THE SUBJECT OF TATAU AND MALU

Wendt’s story, like Figiel’s novel, is written after but set before political independence; it traces the way tatau serve as a flash point in the circulation of power. Wendt and Figiel show that even when they are incomplete, tattoos signal a radical change in the tattooed character’s place in the world and indeed the world itself. Both writers remake the conventions of literature and language in order to portray this newness, emphasizing the materiality of the signifier as they create a written version of the tattoo. For Wendt, a debased realism gives way to a tattoo-based revelation; for Figiel, proleptic and partial translations of the Samoan tatau terms she uses create a narrative structure that follows and completes the design of an incomplete malu or full-body female tattoo.

The tattoo in Wendt’s portrayal, created on the boy’s hand by the prisoner, makes the boy aware of himself as a subject and marks him, in his mother’s terms, as “grown up” (“Cross,” 20). “The Cross of Soot” uses metaphors that render the apparently smooth surface of realism almost diseased, beginning with Wendt’s opening sentence: “Behind him the hibiscus hedge was b...