![]()

CHAPTER 1

ADAPTABILITY

The Bittersweet Culinary History of the English West Indies

Sweetness is a desire that starts on the tongue with the sense of taste, but it doesn’t end there.

Michael Pollan, The Botany of Desire

THE ORIGINS OF AMERICAN COOKING might have started with sweetness, but sweetness got off to a sour start. When Christopher Columbus made his second voyage to America in 1493, he stopped in the Canary Islands to pick up a barrel of sugarcane stems. Although Native Americans had never grown the crop, sugar was a plant that Columbus, whose mother-in-law owned a small sugar plantation in Madeira, thought might thrive in the rich soil of the West Indies. When he planted the samples in Hispaniola, however, he confronted an unexpected problem. The rapid proliferation of brown rats suggested that Columbus had loaded more than just cane stems and provisions onto the Santa María during his brief sojourn. Rats also sought familiar comforts in a strange land, and, much like the Spanish—who were gulping down imported wheat bread, olives, olive oil, garlic, and gluttonous quantities of red wine—the rodents gorged themselves on flavors to which they were also well accustomed. They did what rats had done for thousands of years: they infested fields of freshly planted cane shoots, becoming pervasive pests before the Spanish planters had even harvested their first modest sugar crop. For the Spaniards, these rats multiplied into nagging and persistent reminders of home.

Most Spaniards reluctantly tolerated the nuisance of living with a rat population that soon outnumbered them. One individual, however, was bothered enough by the gnawed canes scattering his small garden to take action. How this particular man (whose name escapes the legend) obtained his misinformation remains unknown, but someone, somehow, convinced him that the solution to the island’s rat problem could be found in, of all things, the mongoose.1 An Indian mongoose at that. This enterprising planter, under the impression that the mongoose would hunt West Indian rats with the same fervor that it attacked cobras back home, arranged to have several mongooses imported to the Spanish West Indies. When the creatures arrived, the planter set them free to extinguish the rodents.

The planter, it turns out, had made a terrible mistake. The mongooses promptly disappeared, whereas the rats, by contrast, continued to thrive on sugarcane. And, to make matters worse, the island’s supply of fowl diminished. The reason was simple enough. The Indian mongoose is diurnal—it feeds during the day. The rat forages at night. On the West Indian islands, the rat and the mongoose passed each other at dusk and dawn, leaving the rats to proliferate as they had always done while the mongooses adjusted to life in the New World by competing quite voraciously with Spanish hunters for a scarce supply of wild birds.

How the Spanish Adapted Sugar to the Caribbean and Destroyed the Native American Population

The legend of the rat and the mongoose is exceptional because, if indeed true, the planter’s act would have been just about the only sugar-related decision made by the Europeans to backfire. These animals might have passed in the night, but the sugarcane taking root in the West Indies burrowed into the soil and climbed toward the heavens. For the better part of four centuries, sugar did nothing less than dominate life in the West Indies. Because the ways in which colonial Americans ate responded directly to the ways in which they worked the land, we must take a close look at the history of that dominance.

Nature engineered sugar to adapt and thrive. Sucrose is an organic chemical belonging to the carbohydrate family. The cane from which it grows is in fact a type of grass whose scientific name is Saccharum officinarum. Civilizations with tropical or subtropical climates have grown sugar for more than ten thousand years, beginning in New Guinea and moving on to the Philippines, India, Egypt, the Azores, and, finally, the New World with Columbus. Sugar’s history of seamless adaptation to foreign climes owes its success to asexual propagation. With decent soil, ample moisture, and frequent sunshine, a single stem graced with a single bud can cover a cleared field with tender green shoots in a matter of weeks. No cross-fertilization required. On the islands of Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, Spanish planters embraced the welcome discovery that their neatly planted rows of cane shoots reproduced abundantly. Growing almost an inch a day for six weeks, the stalks reached an impressive plateau of about fifteen feet, ripening sixteen months after planting. Sugar, if the first few decades of Spanish experimentation were any measure, seemed tailor-made for Spain’s West Indian venture. It comes as no surprise that, as early as the 1520s, planters were exporting small amounts of the “white gold” back to Europe, tempting the taste buds of many of a café dweller, urging them to demand more while watching the price of their new commodity tick upward.

But sugar asked for a lot in return. For one, it sucked the life out of the soil, requiring twice the nutrition of the native maize. If the Spanish really wanted to capitalize on sugar exportation, they would have to spread the crop over vast stretches of land. Therefore, the most obvious obstacle, at least from the Spanish perspective, was the Taino Indians, who had been living on Hispaniola for almost fifteen hundred years.2 They had no intention of stepping aside to make room for a foreign crop that sweetened tea and rotted teeth, much less a foreign people hoping to become rich off such a frivolity. The Tainos had moved to Hispaniola (and Cuba) from South America around the time of Christ’s birth. They developed a peaceful and cohesive civilization that, despite attacks by Caribs, eschewed war and integrated its ways into the natural rhythms of the islands on which they lived. The canoe (canoa), hammock (hamaca), and relatively spacious, circular homes constructed of river cane and palm leaves marked the Tainos’ landscape and culture with an aura of sensible adaptation to a unique environment. In terms of industry, the Tainos manufactured jewelry from coral, shell, bone, and stone. They wove baskets, embroidered cotton belts, carved wooden chairs, and decorated pottery. As far as we can tell, they lived a generally quiet, healthy, and harmonious life.

The Tainos’ dietary habits especially reflected their responsiveness to the island’s natural environment. They obtained their protein from fish and wild animals (mainly snakes and birds) and cultivated manioc (yuca), sweet potatoes (batata), peanuts, and various squash, peppers, and beans. The Tainos grew these crops haphazardly, mixing them on small mounds, or conucos, carefully molded to prevent erosion and maintain well-irrigated soil. These foods successfully intermingled with a variety of wild root vegetables that served to further resist erosion, produce minerals, and provide raw material for potash. Cassava became the most popular of these roots. The Tainos would grub up cassava, squeeze out its poisonous juice (prussic acid), and bake the doughy root into flat bread. The Spanish might have eyed this land with a covetous glare, but, as the Tainos saw it, the land was their land, their sacred space, their ancestral home, their source of food and happiness. And they had no intention of going gently.

Never one to be deterred by such circumstances, Columbus—who admitted to his journal that the Tainos were “the best people in the world3 and above all the gentlest”—entertained a solution consistent with Spanish goals: relocate them. In 1495, after it had become clear that the Native Americans were unwilling to cooperate as servants, Columbus sent four hundred Taino Indians from Santo Domingo to Seville with the explicit intention of selling them into slavery. The plan never fully materialized, and each year until 1499 his shipments of Taino refugees diminished before fizzling out completely in 1500. It wasn’t that Spain didn’t want slaves. The Spanish had, after all, been using African slaves in the Canary Islands for decades. It was rather that the queen didn’t approve of Columbus’s presumptuous aggrandizement of what she now considered her barbarian (but potentially Christianized) subjects. “What power from me has the admiral to give anyone my vassals?” she asked. There was also the issue of the Tainos’ failing health. One Genoese trader remarked on their poor suitability as slaves, saying, “They are not a people suited to hard work,4 they suffer from the cold and do not have a long life.” The cause of the Tainos’ unpopularity in the Spanish slave market, another merchant surmised, was due to “unaccustomed cold.”

The weather had nothing to do with the Tainos’ enervation. Instead, it was biological disaster that altered and ultimately settled the incipient land dispute between the Spanish and the Tainos. The most deadly stowaway that the Spaniards smuggled to the New World was smallpox. More than any other single factor, smallpox cleared the land of its local inhabitants.5 However one tries to spin the story of America’s agricultural origins, planting cane shoots came at nothing less than the cost of an unfathomable human tragedy carried out by invisible but highly contagious microbes. It was a disease for which the Spanish had evolved immunity but the Native Americans, having lived in isolation from the world’s most deadly pathogens for thousands of years, had no defense. And so, with ruthless logic and precision, smallpox decimated them in perhaps the most devastating “virgin soil epidemic” in world history. The numbers are disputed but, according to one authoritative estimate, Native Americans on Hispaniola declined from 3 to 4 million strong before European contact to near extinction sixty years after Columbus’s arrival.

This turn of events hardly caused the Spanish to pause. In fact, with the land now cleared of so many Native Americans, it may have actually intensified their quest to plant and process the product that gave rats more reason to live. After all, God obviously was telling the Spanish that they were a superior people divinely ordained to exploit the landscape as they saw fit. Or so they thought. Whatever the rationale, the Spaniards forged ahead. They planted sugar, battled rats, and slowly but surely built small but viable plantations on Spain’s arc of Caribbean possessions. The process began incrementally, almost unthinkingly, but it proceeded nonetheless. Relying on technology that had not changed since the tenth century, and using presses originally designed to process olive oil, Caribbean planters tried and repeatedly failed to manufacture serious amounts of sugar between 1505 and 1520. Experimentation was rampant, but exportation was minimal. The diminished presence of the Tainos, however, sparked a period of rapid sugar expansion supported primarily by the importation of the animal-powered sugar mills. The transition to more ambitious sugar endeavors also hinged on the importation of sugar masters from the Canary Islands to teach otherwise ignorant planters how to process cane. The infrastructure of economic success was, in short, slowly coming together.6

Armed with these assets, a handful of renegade planters began to consolidate the sugar industry while the rest of the colony continued to search for real gold. With plans for a vertical three-roller mill on hand and a competent sugar maker at the ready, Cristobal de Tapia of Santo Domingo built a fully equipped sugar plantation in 1522, powering his mill with a team of eight oxen. Tomás de Castellon of Puerto Rico received a grant to establish a similar sugar mill in 1523. Francisco de Garay followed suit from Jamaica in 1527. Scores of mills eventually dotted the landscape as the quest for gold proved increasingly elusive and the demand for sugar potentially explosive. The mills arose to accommodate the productive sugar farms that the Spanish settlers had been developing for about a decade. Royal support in the form of loans and land grants from Charles I came through to provide financial support for these ventures. By the 1530s, the infrastructure was starting to pay off. The Spanish were coming to enjoy a nascent but quite sound system of West Indian sugar production that operated under the constant groan of rolling mills.

As well as the groan of involuntary labor. With the surviving Tainos proving to be chronically unreliable workers, in both the hollow gold mines and the lush sugar fields, Spanish planters began to import African slaves to plant their cane, power their mills, and fabricate their sugar. At first, the enslaved Africans trickled into the islands. De Tapia, for example, imported fifteen slaves obtained from Portuguese traders to operate his new Santo Domingo mill. But as the mills proved moderately successful, as a few more modest royal grants came through, and as the Dutch and Portuguese tightened their greedy grasp on the slave trade with lucrative state-sponsored contracts, the slave supply increased. By the 1530s, it wasn’t unusual to find plantations brimming with 150 to 200 slaves. De Castellon, who established the first Puerto Rican mill, reported nearly 3,000 slaves on the island by 1530 (compared with only 327 whites). By the 1540s, slave importers were counting by the thousands. And by the 1560s, plantations with 500 or more slaves were hardly anomalous. Few could have predicted what the future held in store, but from the comfortable perspective of hindsight we know that these sugar pioneers were about to give birth to a slave society.

None of it was really planned. The Spanish had originally settled to find gold and support themselves by planting wheat, growing grape vines, and cultivating barley. Throughout the early sixteenth century, however, they realized that the original rationalization of “God, glory, and gold” might reasonably take a back seat to the pursuit of growing and selling sugar. Settlement and plantation development, the planters began to think, could replace the initial plans for extraction and expansion. These men might not just conquer a world in the name of king and country but, with sugar, shape that world to better sustain their own personal fantasies of grandeur. Through the potentially enormous profits generated by “white gold,” sugar might not just sweeten European coffee, but become something much, much bigger: the basis of a new society—a society where planters ruled.

These dreamy notions became the sweet stuff of settlers’ ambitions, sustaining the bountiful hope of a rich and possibly even independent society on Spain’s colonial fringe. Much to the amusement of the Spanish elite back home, sugar planters even mustered the gumption to apply for titles of nobility. None were granted, but the hubris behind their requests speaks volumes about sugar’s role in shaping the early culture of the Spanish West Indies. For Spanish planters building plantations between 1530 and 1580, in stark contrast to their young black workforce, the future looked bright.

Sugar Production, Slavery, and the English Takeover of the Industry

Grand dreams thus proliferated throughout the Spanish West Indies—but dreams are all that they remained. In order to understand how the Spanish ultimately lost the international bid for West Indian sugar, and to see how the English consequently came to dominate it, we must first take a closer look at sugar itself—the way it was grown and the many tasks it required. For it’s only in the intricate details of production that the importance of this crop to American foodways begins to emerge.

Growing sugar was, for the most part, a relatively basic affair.7 Sun, soil, and water fueled the photosynthetic reactions that fattened soaring stalks of cane without constant planter intervention. Once ripened, though, sugarcane became an impatient and impetuous crop, demanding ongoing human labor. If its juice, with 13 percent sucrose content, wasn’t extracted within two weeks after ripening, the canes dried, rotted, and fermented. The window of opportunity for harvesting this crop was therefore brief. There was no way around it: capitalizing on sugar required laborious efforts by planters hoping to reap nature’s bounty in the quest for economic profit and, perhaps, a little personal fame.

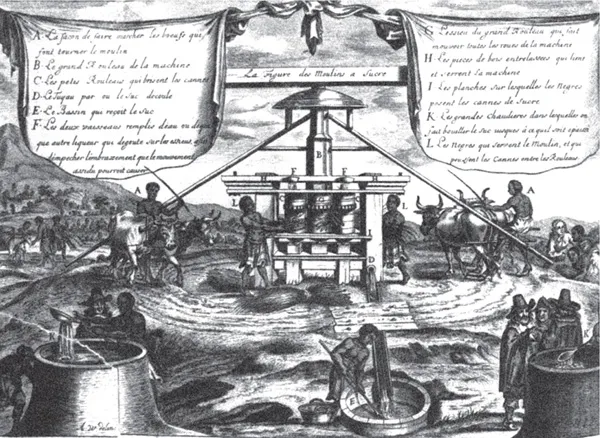

With the harvest’s onset, workers dove into their tasks. They hacked canes at their tough bases with long, curved machetes, loaded the reedy stalks into wooden oxcarts, and hauled them to the plantation’s three-roller mill, which was powered by oxen, horses, wind, or water. The machines and techniques used by the Spaniards were the same as those that had been used by the Portuguese since the late fourteenth century; the work was skilled, but there wasn’t much of a learning curve to master. For hours on end, men unloaded piles of cane, passed them down a human chain, and delivered them to mill workers who pushed and pulled the canes through wooden rollers until they flattened into dry husks. The extracted juice seeped into a funnel, from where it flowed to the next stage of production. Workers saved the mashed canes to burn as fuel.

Slaves processing sugar in the West Indies

The canes had to be crushed in a three-roller mill soon after cutting, or they would dry out.

They next gathered the liquid in large pots and boiled it. The moment when impurities separated from the sugar called for immediate action. If the mixture boiled too long, the impurities might redissolve and taint the entire process. Strikers, as they were called, removed the liquid from heat at exactly the right moment and allowed the cleaned solution to thicken into a syrup called massacuite. After letting the mixture rest for a few hours, boilers reheated it and added egg whites, animal blood, or a substance called milk of lime. This material was made in a lime kiln by dissolving burned lime into water. When mixed with cane juice, milk of lime removed even finer impurities from the cane—stuff like dirt, pigment, tannins, and other complex carbohydrates. Like a moth to a flame, these impurities coagulated around the milk of lime, forming small brown clumps that were easy to remove with a skimmer. After heating the solution to yet another boil, slowly lowering the heat, adding another round of milk of lime, skimming off more scum, and delivering a final blast of heat, the boilers and strikers finally sent a thick, dark distillation of massacuite to the next team of workers.

Collecting the purified sugar in large, shallow pans, workers once again boiled off excess water. This process resulted in a gooey substance consisting of about 60 per...