![]()

1

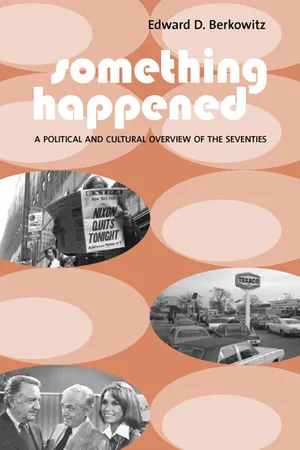

Nixon, Watergate, and Presidential Scandal

During the seventies, America devoured its presidents in what journalist Max Lerner described as fits of “tribal cannibalism.”1 Richard Nixon, the first of the era’s presidents, sent the institution on a downward spiral. The Watergate scandal that resulted from his misuse of power became one of the era’s signature events. It altered the course of electoral politics after 1973, enabled the legislative branch of government to gain power at the expense of the executive branch, increased the level of scrutiny of a president’s private behavior, and made Americans more cynical about the government’s ability to improve their well-being. Watergate also changed the career paths of politicians who aspired to the presidency. Beginning in 1976, governors, rather than senators, became president.

THE LIFE OF RICHARD NIXON

Richard Nixon, an intensely private man, lived one of the most public lives in American history. He was perhaps the last of the twentieth century politicians whose life spooled like a newsreel across the public imagination. Born in 1913, he spent his entire political career in the postwar, rather than the New Deal, era. The southern California of his youth resembled the pages of a John Steinbeck novel more than it reflected the glamour of nearby Hollywood. Still, Nixon found the means to attend college, a fact that set him apart from most people his age. Graduating in 1934 from Whittier College, a Quaker school located near his hometown, he earned a scholarship to the newly established Duke Law School, finishing third in his class in 1937. At Duke he lived in such humble surroundings that he showered in the school gym. His situation reinforced his view of life as a struggle. He practiced law in Whittier before the war brought him briefly to Washington, D.C., for a job at the Office of Price Administration. In the Navy, he served as a transport officer in the South Pacific. Discharged in 1946, he returned home to run for Congress in the California district that included Whittier. Like John F. Kennedy, another Navy veteran and another distinguished postwar politician, he became a member of the Eightieth Congress, part of the insurgency that produced a Republican majority in both houses. It would happen only once more in Nixon’s political career.2

When the Eightieth Congress convened, Nixon had just turned thirty-three. His diligence in pursuing Alger Hiss, accused of being a communist and a Russian spy, made him a household name in his first term. The case became an important touchstone for his career. As people like the president of Harvard fell back on personal ties and a sense of class solidarity to defend Harvard Law School graduate Alger Hiss, Nixon worked around the clock, often in isolation, to expose him. Nixon, it seemed, saw himself as an outsider, despite his spectacular success and important ties to influential citizens and institutions, such as the Los Angeles Times, in southern California. In time, he would win two presidential elections, and his daughter would marry Dwight Eisenhower’s grandson. None of that sapped Nixon’s sense of grievance. Characteristically, victory often made him feel let down and caused him to isolate himself rather than celebrate with others.3

As he smoldered, he advanced to the head of his class in the Republican Party. He climbed the steep step from the House to the Senate in 1950, a faster rise than that enjoyed by political wunderkinder John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, both of whom labored in relative obscurity in the House longer than Nixon. Nixon became an important postwar politician in part because he came from a state rich in electoral votes and, as someone newly on the scene, carried no baggage from the New Deal era in which the Republican Party had been viewed as the party of privilege, a creature of the economic royalists. When he delivered the California delegation to Eisenhower in 1952, Eisenhower and his backers thought highly enough of Nixon to put him on the national ticket.4

Then came another of the signature events in his career. When Nixon was accused of maintaining a secret fund to spend for political purposes, Eisenhower took his time coming to his defense. Eisenhower’s emotional distance reinforced Nixon’s sense that he would have to face adversity alone. Nixon saved himself by going on television and delivering a speech that appealed to the sympathy of the American people. Preparing for the speech, Nixon sank into himself, just as he had during the Hiss case, staying up all night and seeking solitude. “Sleepless nights,” he later wrote in a revealing autobiography, “to the extent that the body can take them, can stimulate creative mental activity.”5 He chose to speak in an empty auditorium, dead tired but summoning up reserves of energy that came from the challenge of the situation. The “Checkers” speech, in which Nixon mentioned a dog that his family had received as a gift, attracted a huge audience of sixty million television viewers.

The next time Nixon acquired such a large audience came in his ill-fated first presidential debate with John F. Kennedy in 1960. Forced to perform in the same room as Kennedy, with the studio warmer than Nixon would have preferred, he began to sweat, smearing the makeup he used to cover his heavy beard and making him look haggard rather than coolly in command. His appearance projected the wrong image in a contest that marked a personal choice as much as it reflected the power of his party to mobilize voters. Once again, Nixon felt betrayed by those he thought should have supported him. Eisenhower made personal appearances on Nixon’s behalf only at the end of the campaign. Nor did Nixon believe that Norman Vincent Peale and other right-leaning Protestants helped him by calling attention to Kennedy’s Catholicism. Once again, the establishment betrayed him.

Nixon moved to New York and went into the private law practice. Remarkably, he worked himself back into contention as a viable political candidate by 1968. He projected himself as a cooler, wiser man than had run in 1960, and this time he won. It helped that the Republicans had no obvious candidate to run since the party’s previous standard bearer, Barry Goldwater, had been annihilated by Lyndon Johnson in 1964. Goldwater ran squarely into the flood of sympathy for the Democrats after JFK’s assassination less than a year before the election. Democrats portrayed him as someone who would have an unsteady grip on the nuclear trigger, a dangerous man. Nixon was, by contrast, a realist and someone who might get the nation back on track after the seeming disarray of the tumultuous events of 1968.

THE ELECTION OF 1968

As befit the self-confident postwar era, both of the presidential candidates in 1968 were former senators who had served as vice presidents in previous administrations. Democrat Hubert Humphrey, Johnson’s vice president since 1965 and the former Minneapolis mayor and Minnesota senator, had lost the nomination to John F. Kennedy in 1960. He received the vice-presidential nomination in 1964 in part because President Johnson could not abide Robert Kennedy and did not want to give him a leg up to the White House. Humphrey won the 1968 nomination as a replacement for Johnson after LBJ decided not to run.

In a close election, Nixon defeated Hubert Humphrey by more than 100 electoral votes, sweeping all of the states west of the Mississippi except for Minnesota, Texas, Washington, and Hawaii. With the exception of Texas, a border state and the home of Lyndon Johnson, Humphrey failed to carry a single state in the Deep South, a region that, until 1948, had stood solidly behind the Democratic Party in presidential elections. In 1968, George C. Wallace, a former governor of Alabama running on the American Independent ticket, took five of the southern states.6

The fact that the Democrats had replaced the Republicans as the party in the vanguard of civil rights raised significant doubts, borne out by the 1968 election, about whether the Democrats could hold on to their southern base. As political guru Kevin Phillips told journalist Garry Wills at the time, white Democrats would desert the party in droves once the party became the home of black voters in the south.7 In the 1968 election, Nixon also made significant inroads among urban ethnics, including Catholics, who had previously been among the most Democratic of voters but who resented the ameliorative measures for blacks that Democrats were supporting.

If the Republicans could maintain such a pattern, it spelled future difficulties for the Democrats, who had been far from dominant in recent presidential elections. Between 1948 and 1968, the Democrats had lost three of the six presidential elections, and two of the others had been extremely close. The coalitions that made up the national political parties had always been tenuous, but the Democrats in modern times had featured a particularly odd marriage of conservative southerners and liberal northern ethnics. Nixon’s election proved that the Republicans could break into this coalition by finding the common denominator between the two groups. Perhaps the bulk of white, middle-class voters who resided in what was coming to be called the Sun Belt could be won over to the Republican cause and united with northern blue-collar workers who were rapidly coming to think of themselves as middle class as well.8 Such a coalition, essentially conservative in outlook, might constitute, as a popular political cliché put it, an emerging Republican majority.

PRESIDENT NIXON

A winner by some half a million votes out of the more than 73 million cast, Nixon followed the model that had been established for postwar presidents. He used his powers to manage the economy, even taking the unorthodox step of imposing price and wage controls in the summer of 1971. Looking to win reelection in 1972, he tried to position the economy so that it peaked at the time of the presidential campaign. He won plaudits for his skilled handling of foreign relations. To do anything else, however, such as passing social legislation, required reaching an accommodation with a Congress that remained solidly under Democratic control. Nixon, as political historians are fond of pointing out, was the first president elected to office since Zachary Taylor in 1848 whose party failed to carry either the House or the Senate. If he proposed a domestic agenda of his own, the Democrats could either vote it down outright or co-opt it. In a bidding war with Congress, Nixon would always lose. He did his best to make proposals that might divide the Democrats, who remained splintered between their southern conservative and northern liberal wings, so as to come up with legislation for which he could take credit.

Whatever he did, it seemed, was not enough to dislodge the Democrats from their hold over Congress. Furthermore, the federal bureaucracy could not be employed easily as an agent of the president’s will. Everywhere there were people, plugged into the congressional committee structure, running programs that ran contrary to the president’s interests. Nixon decided, to the extent that pressing events permitted time for reflection, that he would try to remedy the problem during the second term. In the meantime, he fell back on his natural tendency to hunker down and isolate himself, consciously keeping the details of his policies secret not only from the press but from members of his own cabinet.

THE ELECTION OF 1972

Whatever doubts Nixon had about his performance, he compiled what many regarded as an enviable record during his first term. The Democrats realized they would face an uphill battle if they expected to defeat him in 1972. As usual, a host of senators, such as Henry Jackson, Hubert Humphrey, and George McGovern, announced their willingness to run. So did a few congressmen, such as Wilbur Mills of Arkansas and Shirley Chisholm, a black congresswoman from New York, as well as the mayors of two key cities, John Lindsay of New York and Sam Yorty of Los Angeles. These categories reflected the Democrats’ electoral hold over the Congress and their considerable strength in the big cities.

On March 14, 1972, George Wallace, the one candidate in the race who, with the possible exception of Mayor Yorty, made no claim to close ties with the federal government, beat all of his rivals in the Florida primary. The victory served as a powerful reminder that not all Democrats shared the more liberal ideology and not all Democrats came from the north or the Pacific coast. In his rhetoric, Wallace captured some of the resentments that many people felt toward experts who appeared to rule their lives without any real regard for the consequences and who were themselves quite remote from the daily struggle to earn a living and raise a family. In the campaign, Wallace talked about “the intellectual snobs who don’t know the difference between smut and great literature,” “the hypocrites who send your kids half-way across town while they have their chauffeur drop their children off at private schools,” and “briefcase-carrying bureaucrats.”9 If an unlikely winner of the Democratic nomination, Wallace was nonetheless an important figure in the Democratic primaries, and the prospect of his running as an independent candidate threatened to derail Nixon’s strategy of picking up electoral votes in the South.

The candidate who came into the election with the highest expectations was Edmund Muskie, a former governor of Maine who had won election to the Senate in 1958, 1964, and 1970.10 In 1968 he had made an appealing vice-presidential candidate on the ticket with Hubert Humphrey, and he hoped to cash in on some of that goodwill in 1972. He won the New Hampshire primary that traditionally inaugurated the primary season, yet that showing was expected of the former governor of Maine. He then proceeded to fade in the Florida primary and in the April 4 Wisconsin primary.

The primary beneficiary of Muskie’s collapse was George McGovern. McGovern came from the sparsely populated state of South Dakota and held a Ph.D. in history, putting him squarely in Wallace’s class of intellectual snobs. He had even been a professor at a small, Methodist-affiliated college in South Dakota before practicing politics full-time. In 1956 he won election to the House and ran for the Senate in the Kennedy-Nixon election of 1960. After he lost, he became a minor functionary in the Kennedy administration until he won a Senate seat in 1962. His association with the Kennedys gave him a sense of glamour that he otherwise lacked. In 1968 he became a late stand-in for the assassinated Robert and in 1972, with the help of astute manager Gary Hart, he launched a full-scale campaign. When he won the Wisconsin primary, he succeeded in knocking Muskie out of the race. He was now the front-runner, although he still had to contend with George Wallace.

McGovern and Hart proved adept at leveraging primary wins. A new delegate-selection process that McGovern had helped to engineer put more emphasis on primaries (Humphrey had won in 1968 without winning the primaries) and less on the discretionary choices of political professionals and urban bosses such as Mayor Richard Daley of Chicago. In the new process, the party hoped to be more representative of the people who belonged to it and voted for its candidates. More blacks from the South and more women from across the country would attend the 1972 convention. As a consequence, the proportion of female convention delegates rose from 13 percent in 1968 to 40 percent in 1972.11

In such a party, George Wallace still did surprisingly well, even without the support of blacks or labor unions. By mid-May, Wallace had racked up 3.35 million votes in the primaries.12 At just that time, Wallace made an appearance in the suburban town of Laurel, in the Maryland corridor between Washington and Baltimore. Laurel was the sort of place in which Wallace did well—a predominantly white area in a suburban county that was rapidly becoming black. The white people of Laurel felt they had fled the city and its problems only to find those problems chasing the...