![]()

Part 1

Locating and Citing Source Materials

![]()

1

RESEARCH IN THE ELECTRONIC AGE

The starting point for most research is no longer the library but the World Wide Web. To some, this statement may seem heretical; to others, however, it is merely descriptive: students today are likely to begin any research project by using a search engine to locate material, often with tragic results.

The problem is twofold. First, knowing where to search for reliable information on a given topic is complicated by the chaotic and shifting nature of the World Wide Web. Like trying to hit a moving target, locating sources on the Internet can be frustrating, unreliable, and erratic. Sites move or disappear with alarming frequency, while new ones are constantly emerging. Researchers often find that even with the advantages of electronic search capabilities—the speed with which information in vast databases can be searched, for example—finding useful sources is time consuming and sometimes downright impossible.

Second, many electronically published sources, especially those published on the Web, do not provide enough information to evaluate or cite them adequately. That is, while we can ascertain much about the authority of a print source from its imprint—university press or scholarly, peer-reviewed journal, etc.—a Web site may provide few if any clues to its author, sources, currency, or sponsorship. What clues there are may be difficult to determine without some knowledge of the increasingly transparent protocols that enable Web authoring and publishing in the first place.

Further complicating the dilemma faced by researchers in the dawn of the twenty-first century is the move toward more and more online publication of “traditional” scholarship, especially in the face of severe financial constraints faced by many university presses. While online databases that provide full-text or full-image articles and online-only—or online counterparts of for-print—scholarly journals are a boon to knowledgeable researchers, the result of so much wealth is daunting. The sheer volume of information available online makes it virtually impossible for anyone to know at any given time what’s “out there” and even more difficult to know where to begin looking for it.

In part 1, we present information to guide researchers in their quest for sources, helping them locate information and carefully evaluate it. Where to look for information, we argue, depends first and foremost on the type of information needed—and more and more of this information can now be located online. However, because the online world is still (and we hope will remain) a space with relatively little regulation, we also provide guidelines for evaluating information sources. These guidelines should help the reader come to a better understanding of citation practices as an integral part of research and writing, not only as a way to avoid charges of plagiarism or to fulfill some vague classroom dictates but as central to the act of knowledge building, the bricks and mortar, as it were, in the construction of a given rhetorical act. Thus, we present five principles of citation style as a foundation upon which to build a solid structure.

This second edition of The Columbia Guide to Online Style includes two full chapters of models—one for humanities-style projects (i.e., MLA), and one for scientific-style (i.e., APA), each chapter offering more models than ever before for both in-text and bibliographic formats, covering a wide variety of types of electronic and electronically accessed sources, including those most often being used by students and other researchers in this digital age. Part 2 of this book offers some suggestions for authors and publishers for issues of document production both in print and online for the digital age, for example, responding to changes in standard markup languages and document formats, document-production software, and the proliferation of multimedia publication, including guidelines for basic Web site architecture.

Our intent is not to fix a moment in time by prescribing rigid formulae; instead, we hope to suggest ways to ensure that researchers in a digital world will have the information necessary to adequately locate and evaluate scholarly sources. However, there is no guarantee that authors or publishers will follow these suggestions. The very nature of the World Wide Web, in fact, guarantees that no one standard is likely to be enforceable anytime in the near future. It is thus incumbent on researchers themselves to learn to locate reliable information, to evaluate the information they find, and to document the sources they use as fully and as accurately as the information allows.

1.1. LOCATING INFORMATION

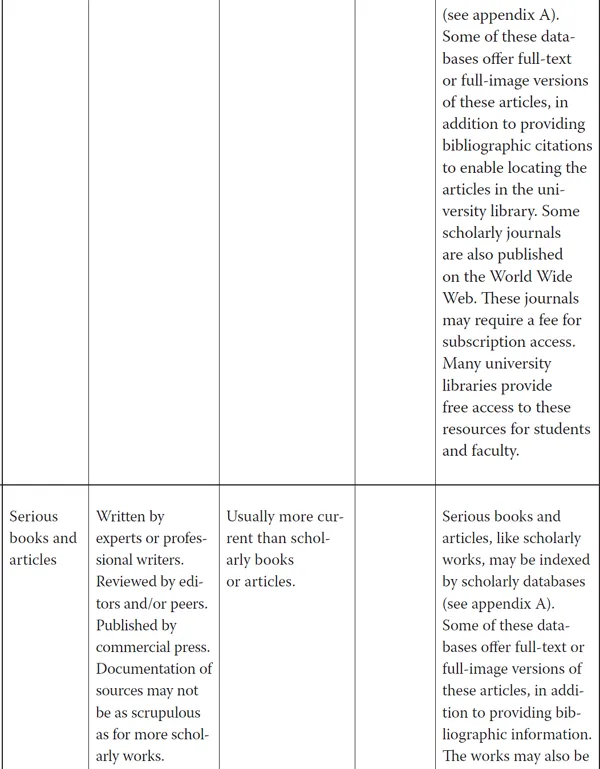

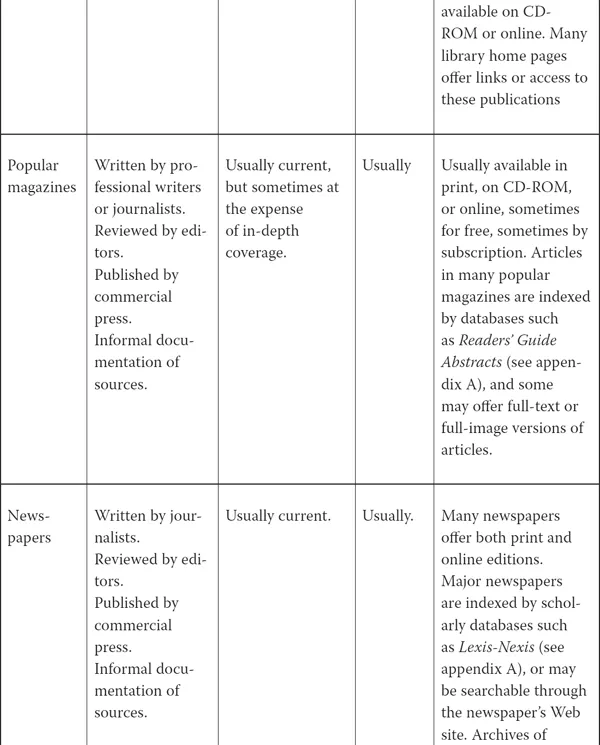

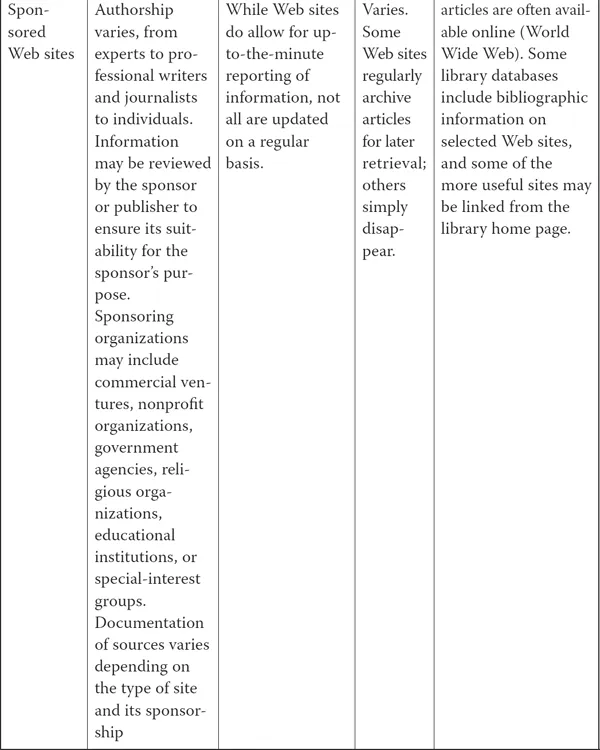

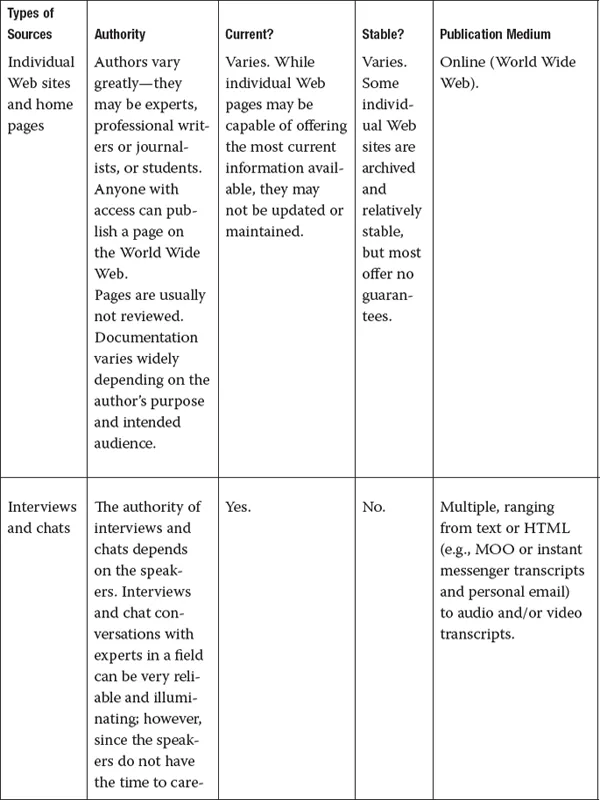

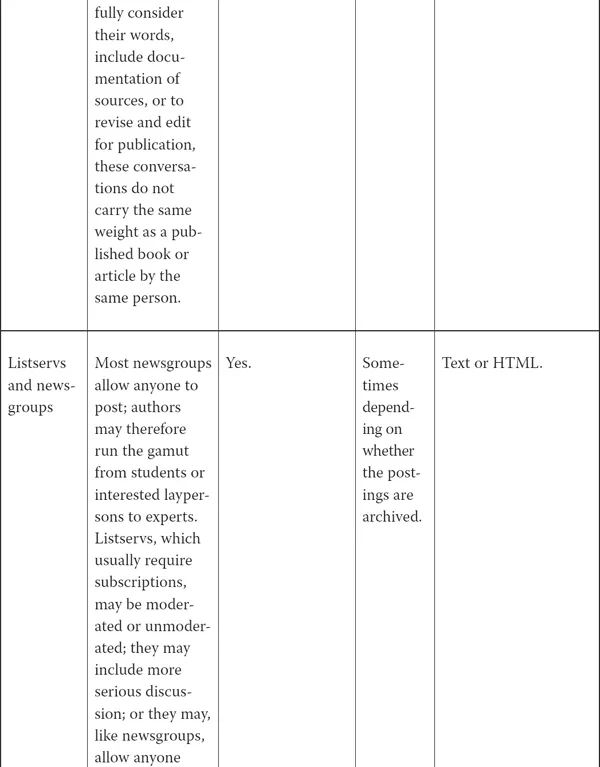

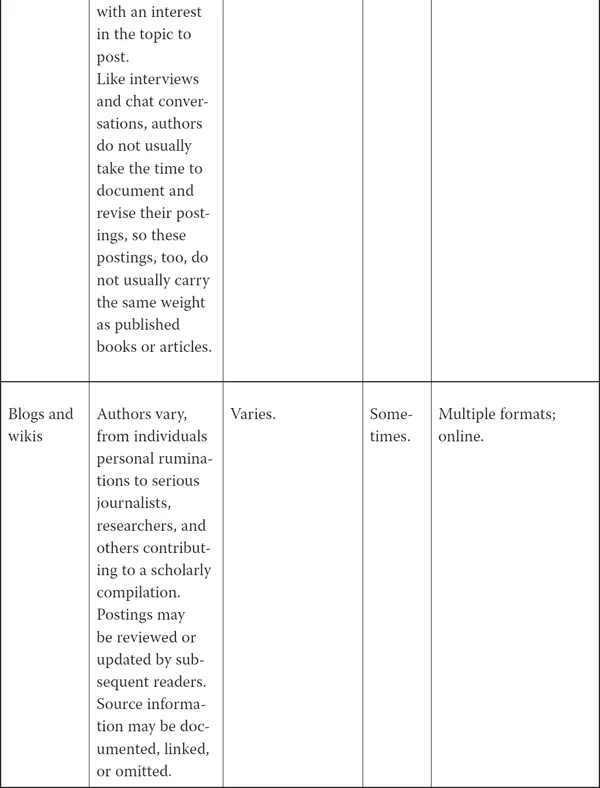

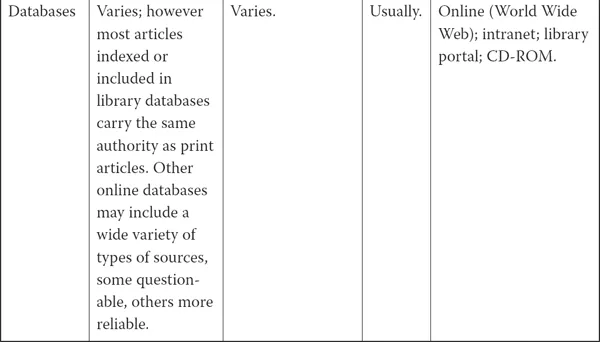

Knowing where to look for information depends to a large extent on the type of information needed. Scholarly projects usually rely on rigorous, peer-reviewed sources (see table 1.1). While many of these scholarly sources are now available online, of course, with many more migrating to digital forms every day, print sources still provide a wealth of information that researchers cannot afford to overlook. Nowadays, locating print sources does not necessarily mean leaving home (or leaving the World Wide Web), since most university libraries now offer students and faculty access to the library catalog, online databases, and many other reference sources through the library’s home page on the World Wide Web. Nonetheless, knowing where to start a search—whether to begin with the library’s home page or an Internet search engine, for instance—requires an understanding of what different types of sources have to offer a researcher as well as where best to locate them. Obviously, the library may not be the best place to look for up-to-the-minute information. Alternatively, the World Wide Web will usually not be the best possible source for finding extended, analytical work on scholarly topics.

TABLE 1.1 Assessing Sources

1.1.1. Search Library Catalogs

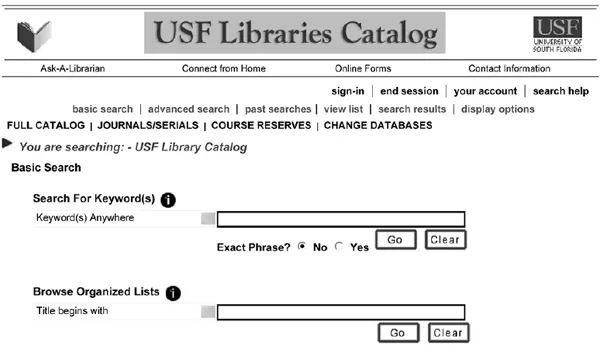

Online library catalogs offer researchers a means to locate scholarly books, journals, and other media quickly and efficiently. Nowadays, most college and university library catalogs, such as the one shown in figure 1.1 from the University of South Florida, are accessible on the World Wide Web, often through the library’s home page, and allow for searches by author, title, subject, keywords, or other identifiers.

It is often possible to search catalogs at other institutions as well, across the street or across the world, to locate material not owned by a local library (see appendix A for a partial list of library holdings that can be freely searched on the World Wide Web).

FIGURE 1.1 The University of South Florida Library catalog.

Source: http://sf.aleph.fcla.edu/F?RN=857882890.

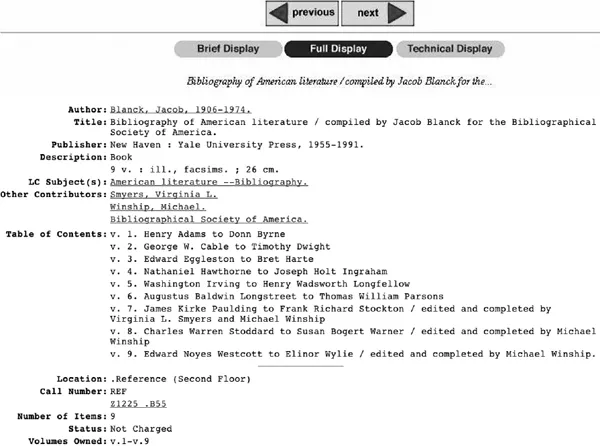

A library catalog search will usually provide bibliographic information about library holdings, including the author, title, publication information, location, status (whether or not the work is checked out), and more, as shown in figure 1.2.

1.1.2. Search Online Databases

Searching databases such as Dissertation Abstracts/Digital Dissertations at ProQuest, the MLA Bibliography, or Academic Search Premier can help researchers locate material housed almost anywhere in the world. Many libraries offer access to a number of powerful online databases, either through their home page or on CD-ROM. Once you have located the bibliographic information, you can determine whether your library owns the material by searching the library’s catalog of holdings. Some databases will locate the material for you or provide full-text or full-image copies online (full-text files do not usually include illustrations or page breaks; full-image resources offer exact copies of original material, including pictures, pagination, etc.). If your library does not own the material, you may be able to order print copies through interlibrary loan, a program that allows member institutions to borrow materials from other member institutions throughout the world, often at no charge. Check with your library for more information. See appendix A for a list of selected databases, available either online, through your library’s Web portal, or on CD-ROM.

FIGURE 1.2 Bibliographic entry from the Zach S. Henderson Library, Georgia Southern University.

Source: http://library.georgiasouthern.edu/.

1.1.3. Search the World Wide Web

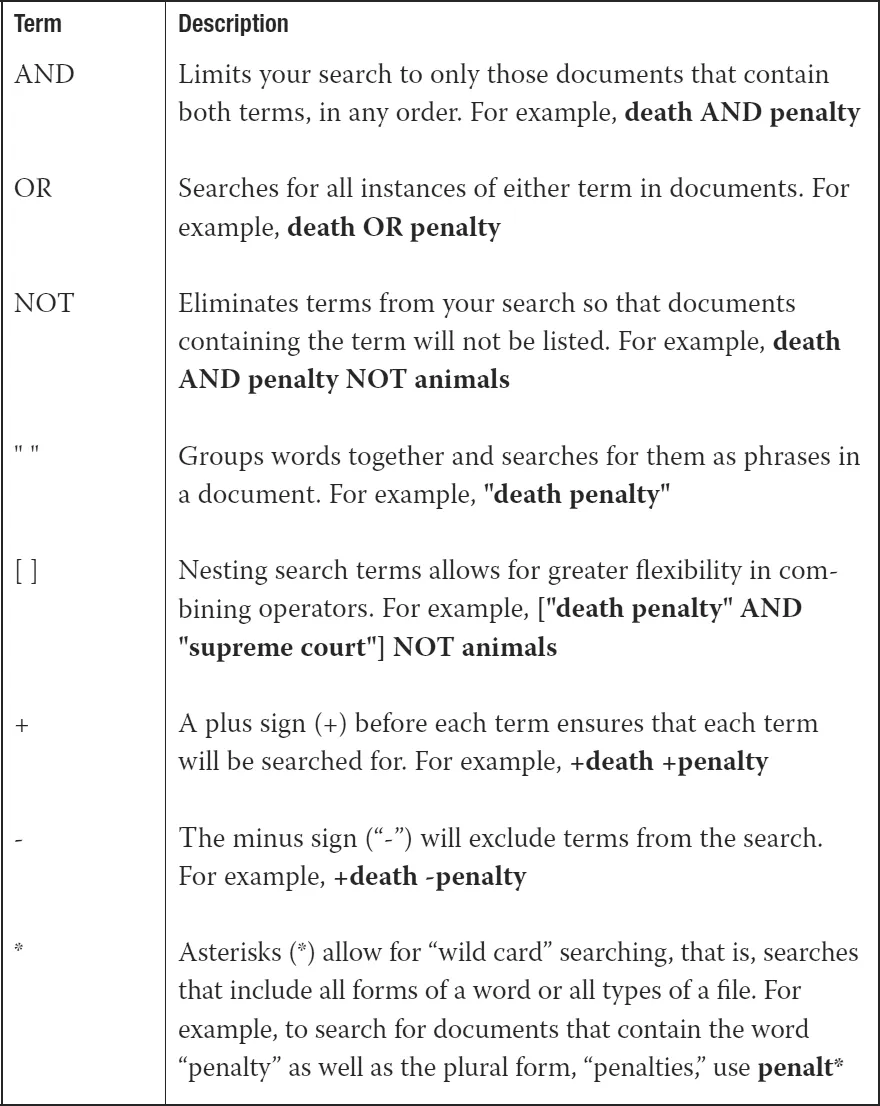

There are many different Internet search engines, each with its own peculiarities. Nonetheless, most of them use similar type search queries, usually plain English keywords. Moreover, many search engines and online databases also allow for more advanced Boolean searches. Table 1.2 illustrates some common Boolean operators and how to use them.

TABLE 1.2 Using Boolean Search Terms.

Different search engines may search different types of sites; thus, if you do not find what you are looking for with one, try a different one. Appendix A includes a list of selected search engines and directories, as well as a list of online collections and general reference sources. Keep in mind that the Internet is constantly changing, so the results you obtain on one day may be quite different on another. Keep a record of important Internet addresses and, for citation purposes, you may also want to keep a record of the date you accessed the sites along with other pertinent information, such as author(s)’s name(s), titles, search terms, etc.

1.2. EVALUATING SOURCES

Most scholarly work published in print formats has undergone a thorough review process by editors and knowledgeable peers (see table 1.1). Unfortunately, other types of sources—both print and electronic—may not be held to the same high standards. Of course, even scholarly publications may become outdated, with information or claims overturned or questioned by subsequent scholars. Researchers must carefully evaluate all of the sources on which they rely in order to ensure the credibility of their own work.

For print sources, ...